The concept of nonhuman photography is fascinating. As the author poses, nonhuman photography can offer new methodologies of perception, displacing the human-centered perspective of the world. New imaging technologies enable the capture of traces and information invisible to human eyes. This could be considered as a way to open up our view to other kinds of realities that are out of the field of vision: “As a practice of incision, photography can help us redistribute and re-cize the human sensible to see other traces, connections, and affordances ”.

Somehow, these new imaging processes and devices can make us aware we are not the only subjective core of reality, there are so many other forces, phenomena and beings that operate in the construction of the world.

Furthermore, through the emergence and use of machine learning algorithms and software, the role of the operator has shifted from the photographic experience. A human entity is no longer required for the photographic act. As the quote states, this intensifies the idea of nonhuman photography as there might be a sentient system or technology that can make decisions about capture and image processes. These new ideas challenge the definition of photography turning it into an assemblage or collaboration of diverse nonhuman actors.

Last year, I experienced a full solar eclipse in Chile. During the eclipse, as sunlight came through branches and tree leaves, they transformed into thousands of pinhole cameras. This allowed the projection of the crescent shadow of the sun to be projected onto a surface. I believe this phenomenon embodies the essential concepts of imaging or photography. Though there is no human intervention, no device, the image comes alive by itself like a mirage.

Although I think that this example does not completely match the theoretical premises of the text (but it is closer to Roberto Huarcaya’s mesmerizing Amazograms) I believe it is a poetic example of a phenomenon that aligns with the essence of image-making or even with a more radical definition of nonhuman.

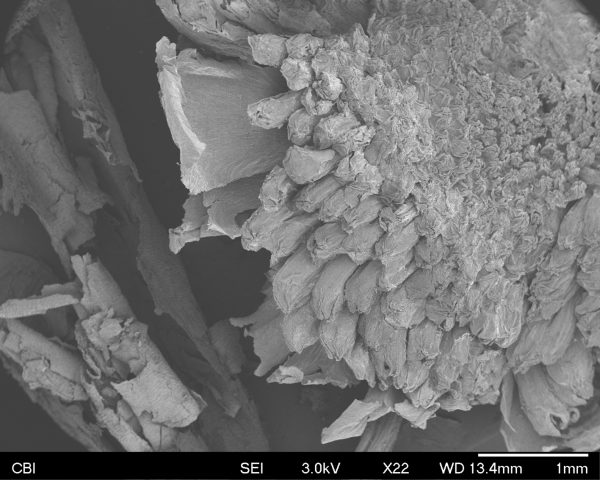

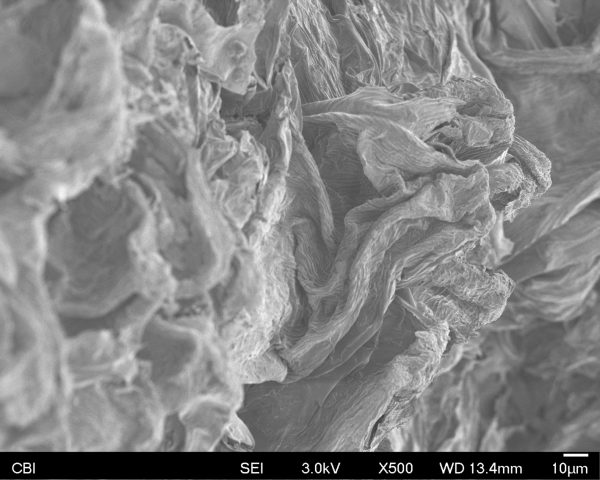

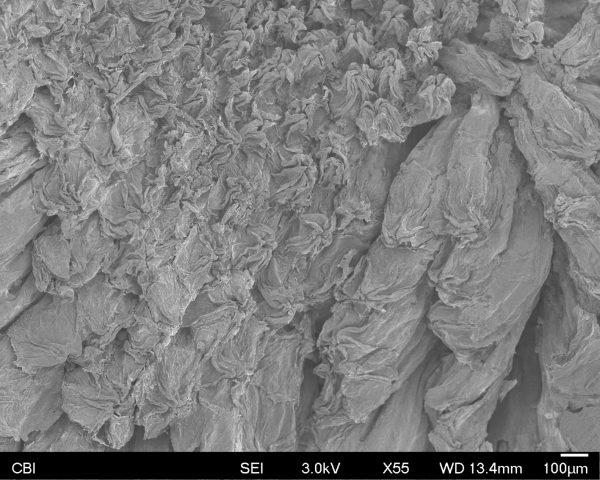

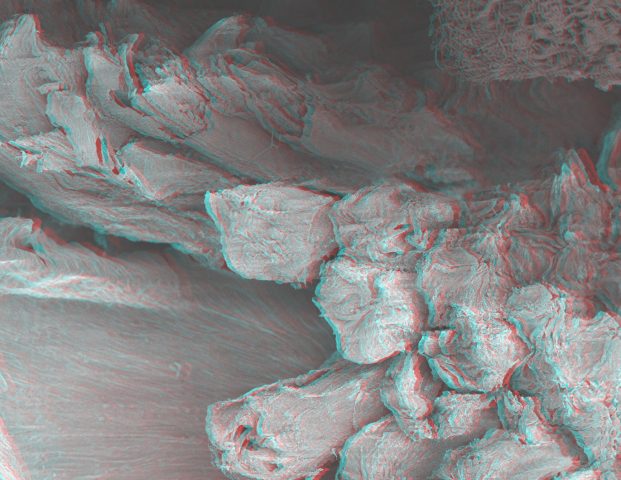

Here are some of the images I took during the eclipse. It was July 2th 2019