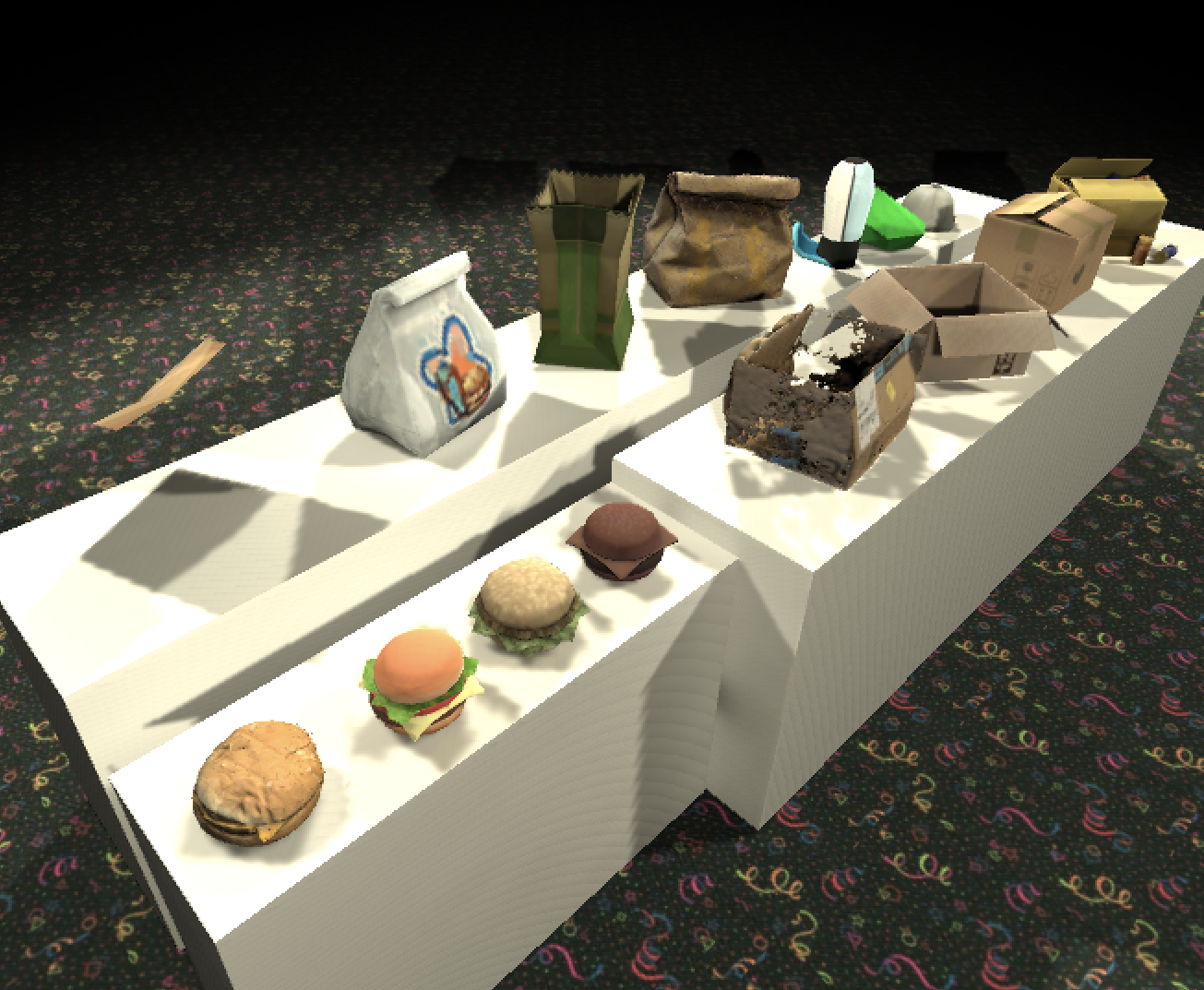

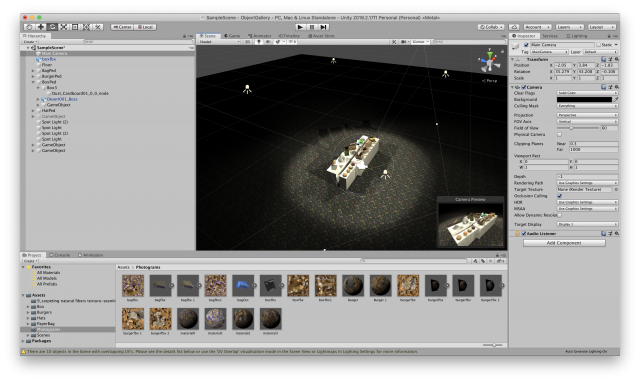

This virtual gallery displays tangible objects captured from real life, accompanied by their mundane and iconic representations from popular video games.

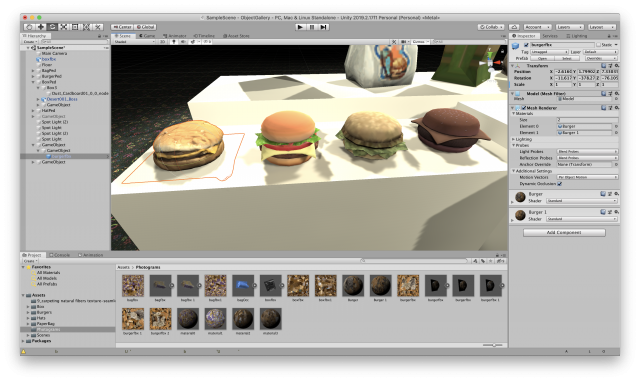

I originally had an idea to curate a similar gallery, which would include samples of real textures alongside their renderings in different styles of illustration. I wanted to capture the process of reconstructing tangible perception in a medium as abstracted as illustration. I eventually found that the variations between styles weren’t cohesive enough to create the type of collection I wanted, so I thought of collecting 3D models, specifically low-polygon models created for video games. This type of modeling is a medium that is abstracted enough by its limited detail, and can assume endless varieties of recognizable forms. It also incorporates some of the gestural aspects of illustration that I was trying to capture, through both the applied image textures and the virtual forms themselves.

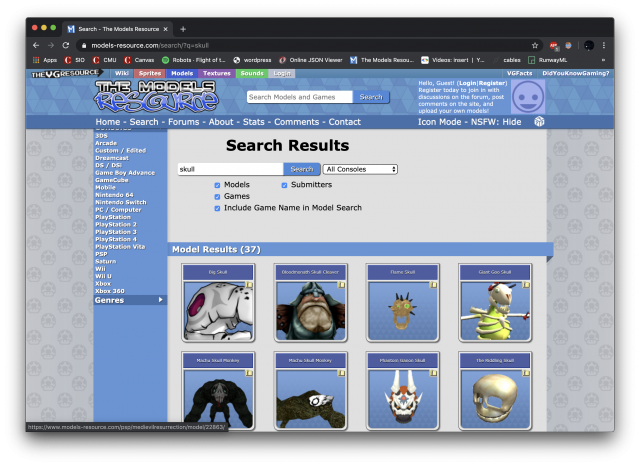

I thought of using video game models for my typology when I was browsing The Models Resource looking for models to use for a different experiment. The Models Resource is a website that hosts 3D models that have been ripped from popular video games. I first noticed that a lot of the models had been optimized for speed and had interesting ways of illustrating their detail with a limited amount of information.

The following are some of the titles from which I sourced models:

- Mario Party 4 [2002] – Wario’s Hamburger

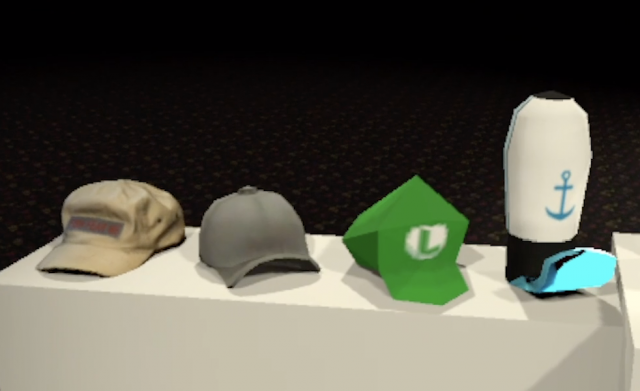

- SpongeBob SquarePants Employee of the Month [2002] – Krusty Krab Hat

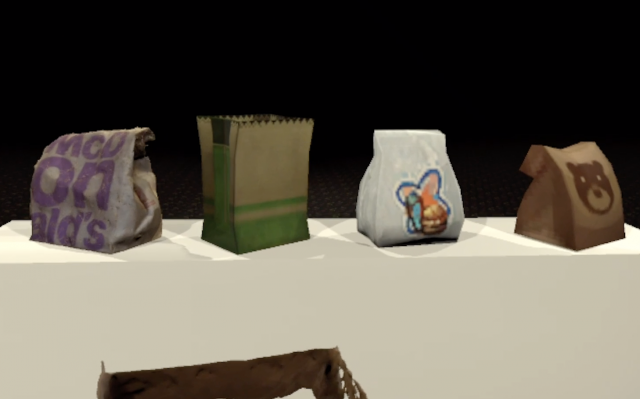

- SpongeBob SquarePants Revenge of the Flying Dutchman [2002] – Krusty Krab Bag

- Scooby-Doo Night of 100 Frights [2002] – Hamburger

- Garry’s Mod [2004] – Burger

- Mario Kart DS [2005] – Luigi’s Cap,

- Dead Rising [2006] – Cardboard Box

- Little Big Planet [2008] – Baseball Cap

- Nintendogs Cats [2011] – Cardboard Box, Paper Bag

- The Lab [2016] – Cardboard Box

- Animal Crossing Pocket Camp [2017] – Paper Bag

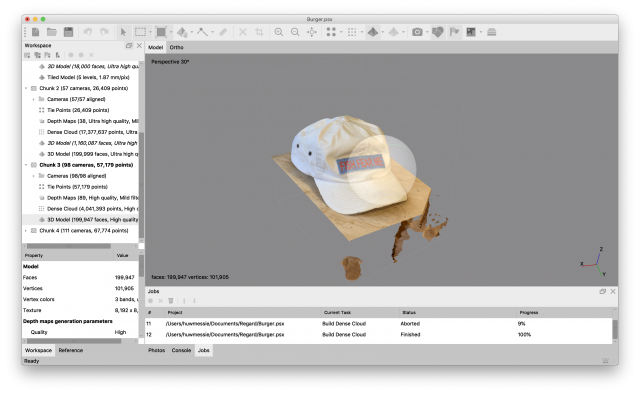

I decided to use photogrammetry to bring physical objects as seamlessly as I could into virtual space. I wanted to contextualize these artifacts which had been stripped from their intended contexts alongside virtual objects which we might consider to be “more real” due to being representations of photography, rather than abstract visualizations.

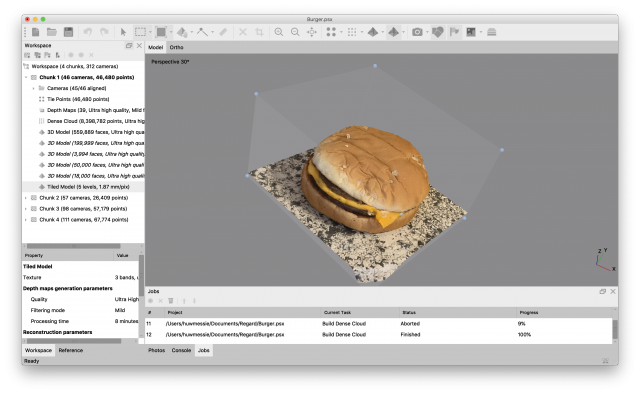

I think that this collection of hamburgers is the most jarring, as it frames a convincing representation of something commonly ate and digested as the plastic and rigidly designed product it truly is. The bun of this McDonald’s double cheeseburger was stamped by a ring out of a sheet of dough, the patty was stamped into a circle by another mold and the cheese was cut or sliced into a regular square – all automated processes of physical manufacturing done with the intent of assembling this product for somebody’s enjoyment.

I noted that many of the examples I found were mostly or entirely symmetrical. I think this symmetry reflects our physical ideals of the products we interact with and consume. A virtual object can exist in an absolutely defined state, rather than existing as the expression of this definition which is only similar enough within manufacturing tolerances. These manufacturing tolerances exist in most of the objects we interact with, and even the food we consume. We seem to use symmetry to indicate the intentionality of an object’s existence, which coincidentally or not, is also used for making most organic bodies. When a video game character is designed asymmetrically, it is usually done so deliberately to call attention to some internal imbalance or juxtaposition.

In retrospect, the disruptions of the photogrammetry – especially in the empty box model – seemed to manifest the essence of our fleeting, tangible perceptions of certain objects compared to others. The items that served as packaging for a product, to be discarded or recycled, are missing information as if easily forgotten.