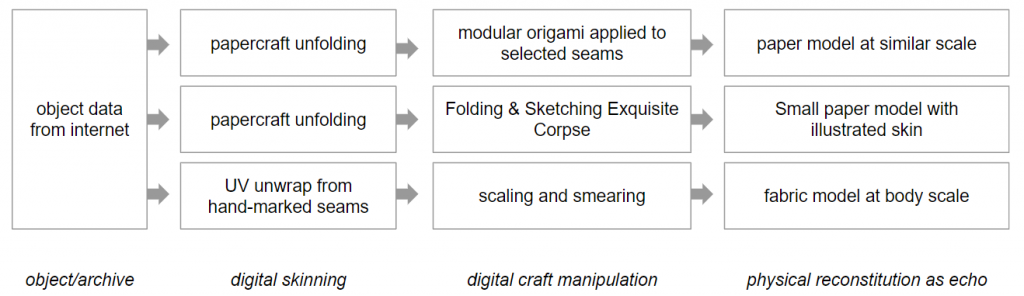

This project uses archived 3d models as a basis for creating ‘reconstituted objects of meaning’ via algorithmic unwrapping and craft-derived digital manipulation.

We align this process with themes of memory and reclamation, recognizing the impossibility of perfect recall/reproduction, especially within the digital/physical flipflop.

Craft Basis

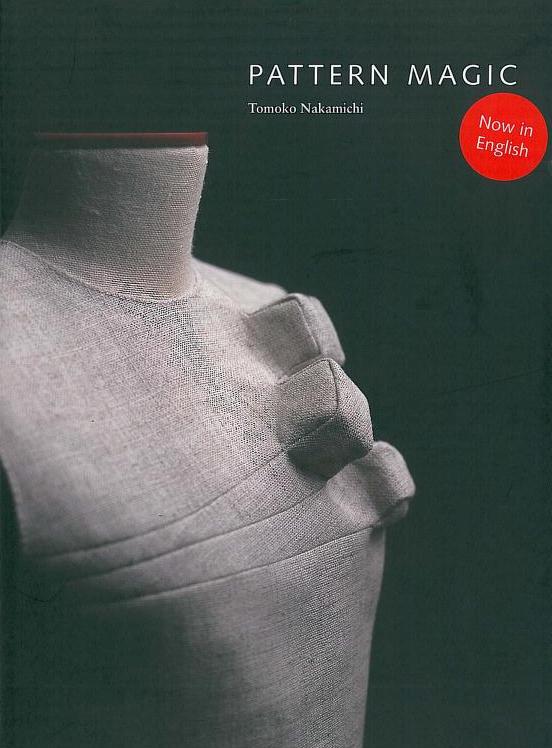

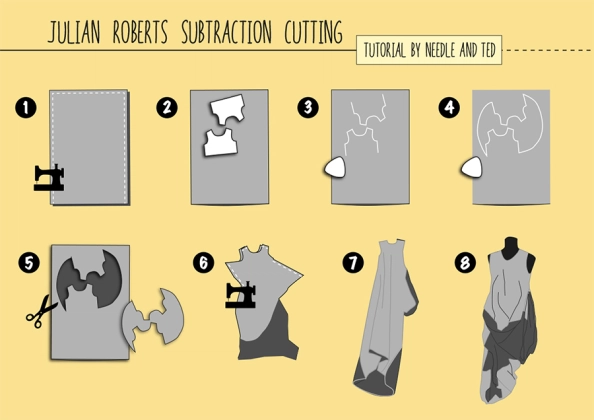

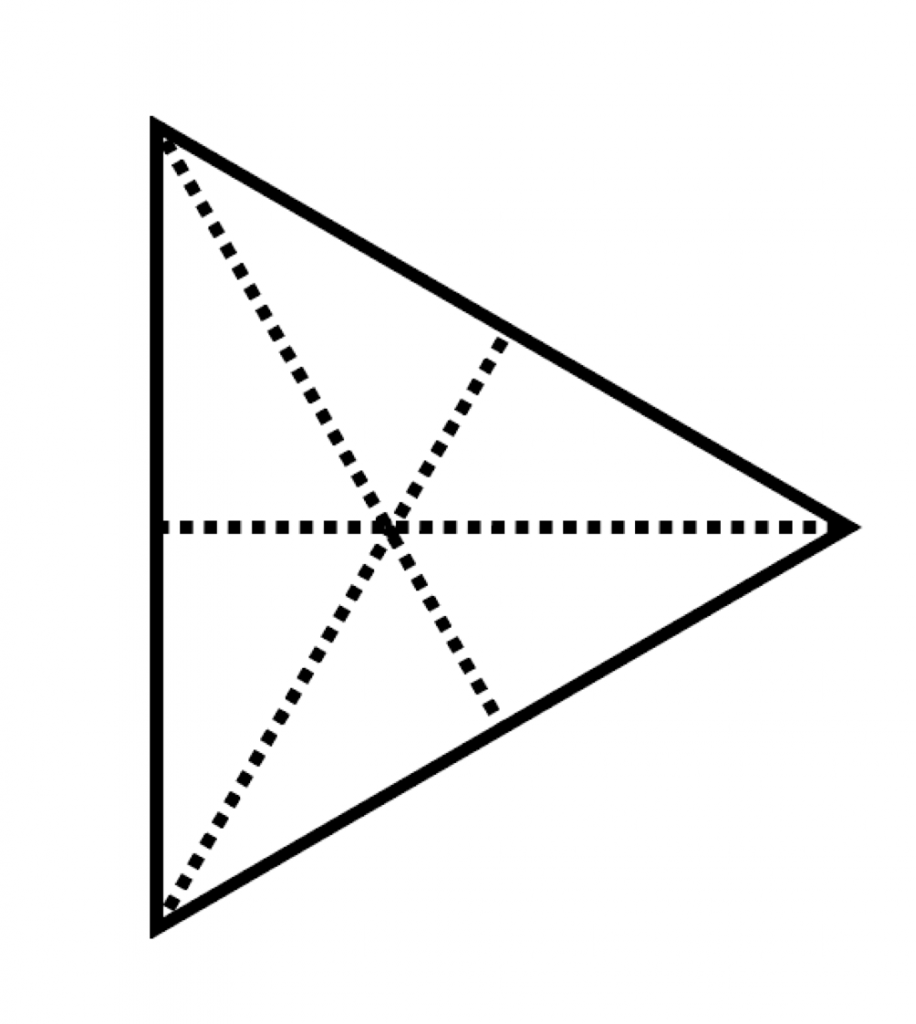

Our goal was to create meaningful deformations through flat pattern manipulation – a family of methods for cutting, translating, and re-marking the unrolled flat pattern of a 3d object to change the final model. There are examples of this type of manipulation in both paper craft and garment production.

“Pattern Magic” by Tomoko Nakamichi: https://archive.org/details/PatternMagic/mode/2up

“The T-Shirt Issue” by Hoid: https://www.hoid.co/product/digital_portraits/

“Subtraction Pattern Cutting” method by Julian Roberts

The Process

Each team member was tasked with first choosing a meaningful object that they didn’t have physical access to, then find a representative model of that thing from an online library. With that model in hand, we followed distinct design pipelines to generate the final model. Our methods were unified by an overarching set of steps.

Our Separate Processes

Celi’s Process

Skinning

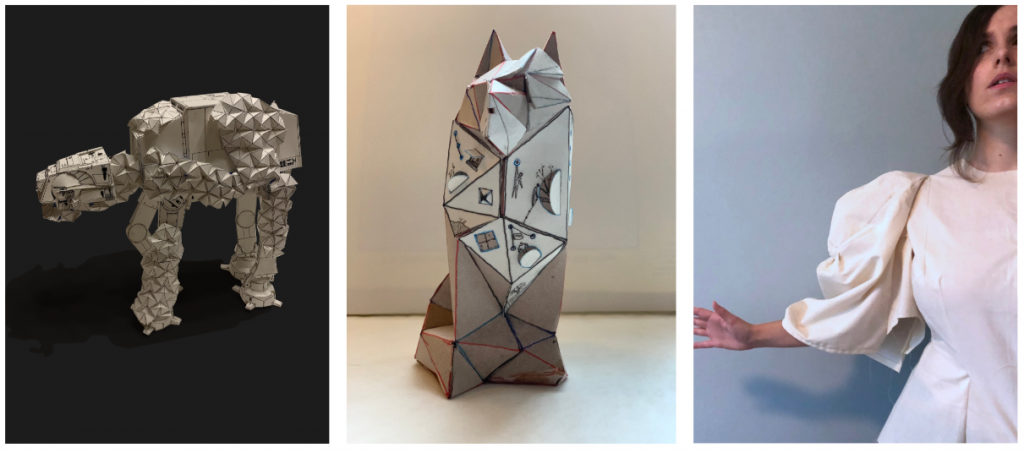

I chose to work with a model of a Star War’s AT-AT that I have at home but do not currently have with me.

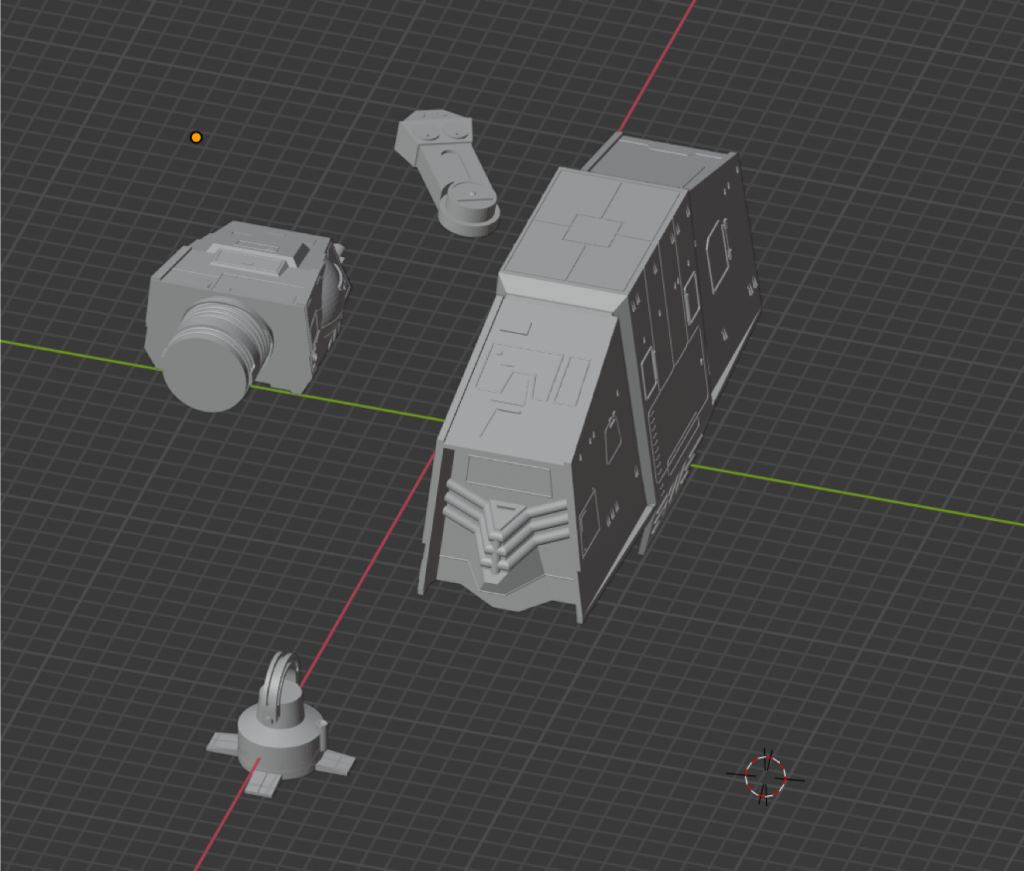

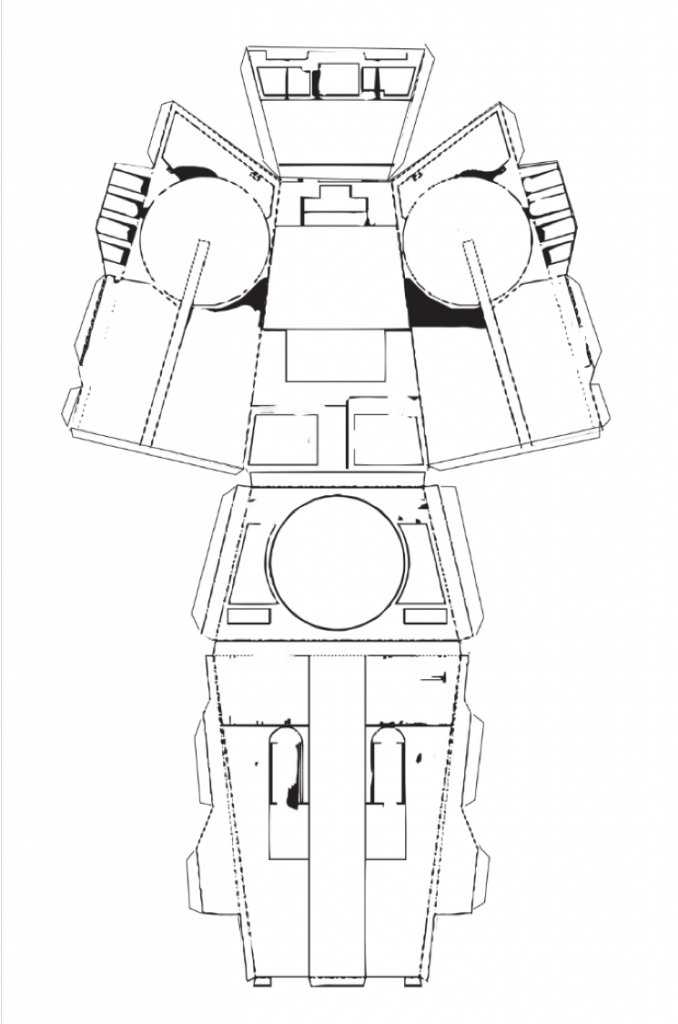

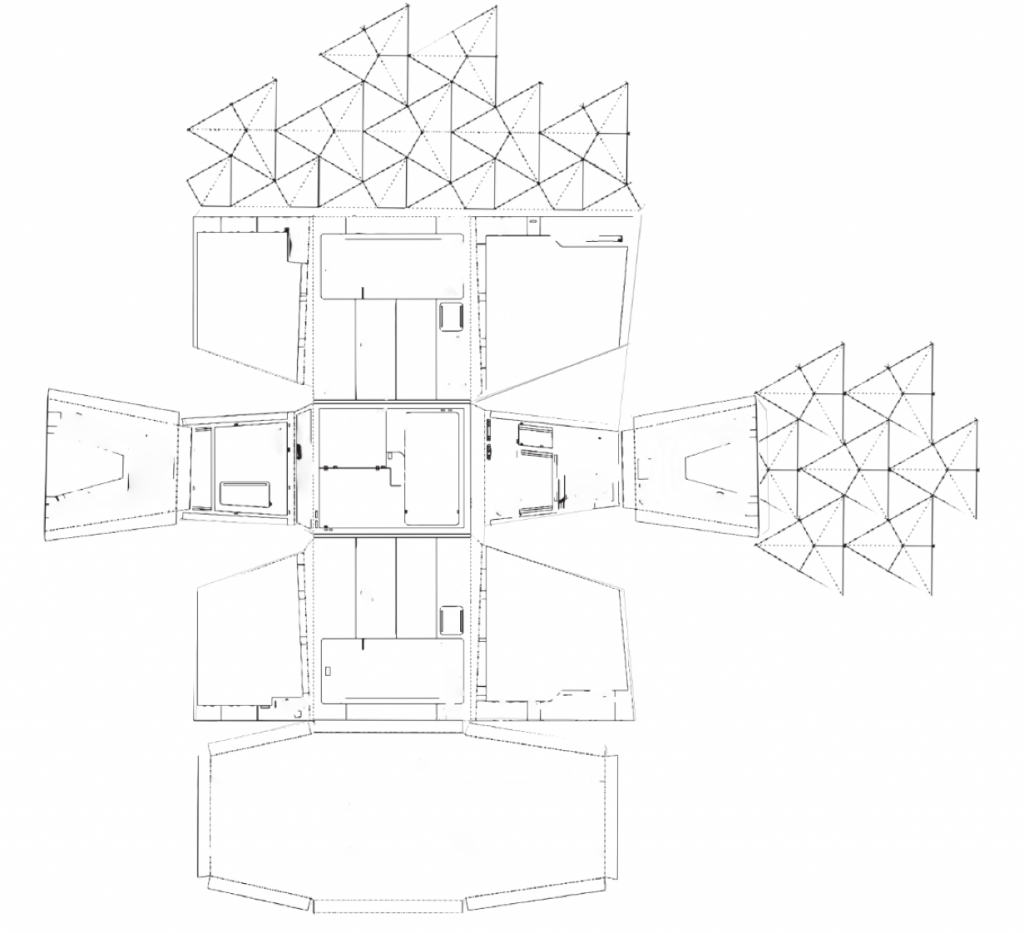

I used Blender to break a model of my object into different sections and then unwrapped each section using the blender Paper Model add-on.

3D model of AT-AT on Blender

Unwrapping of AT-AT head

Manipulation

The goal of my type of manipulation was to create organic growths on my model in order to cover certain parts that I did not remember well. I wanted to use addition material to “blur out” these parts, attempting to simulate what my mind does to parts of the memory of the object.

I created an illustrator script that would output a random-sized growth to designated edges of my unwrapped model’s net. This growth consisted of tessellation origami patterns that could then be folded into an organic-looking addition.

Reconstruction

The reconstruction of my model was made by folding, pasting and reassembling the different parts. The origami additions were folded up onto the model in order to cover up and “blur out” certain parts.

David’s Process

Skinning

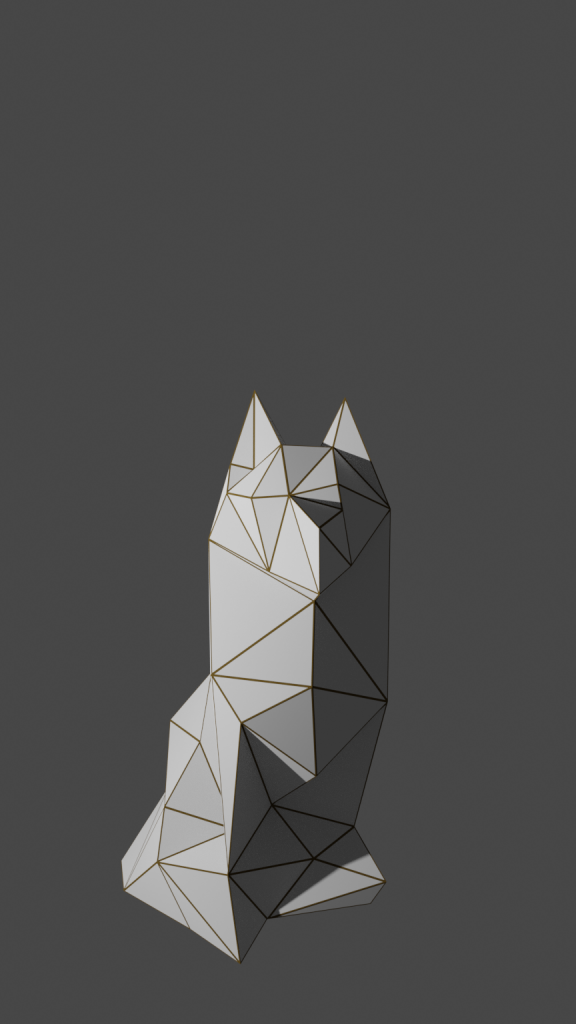

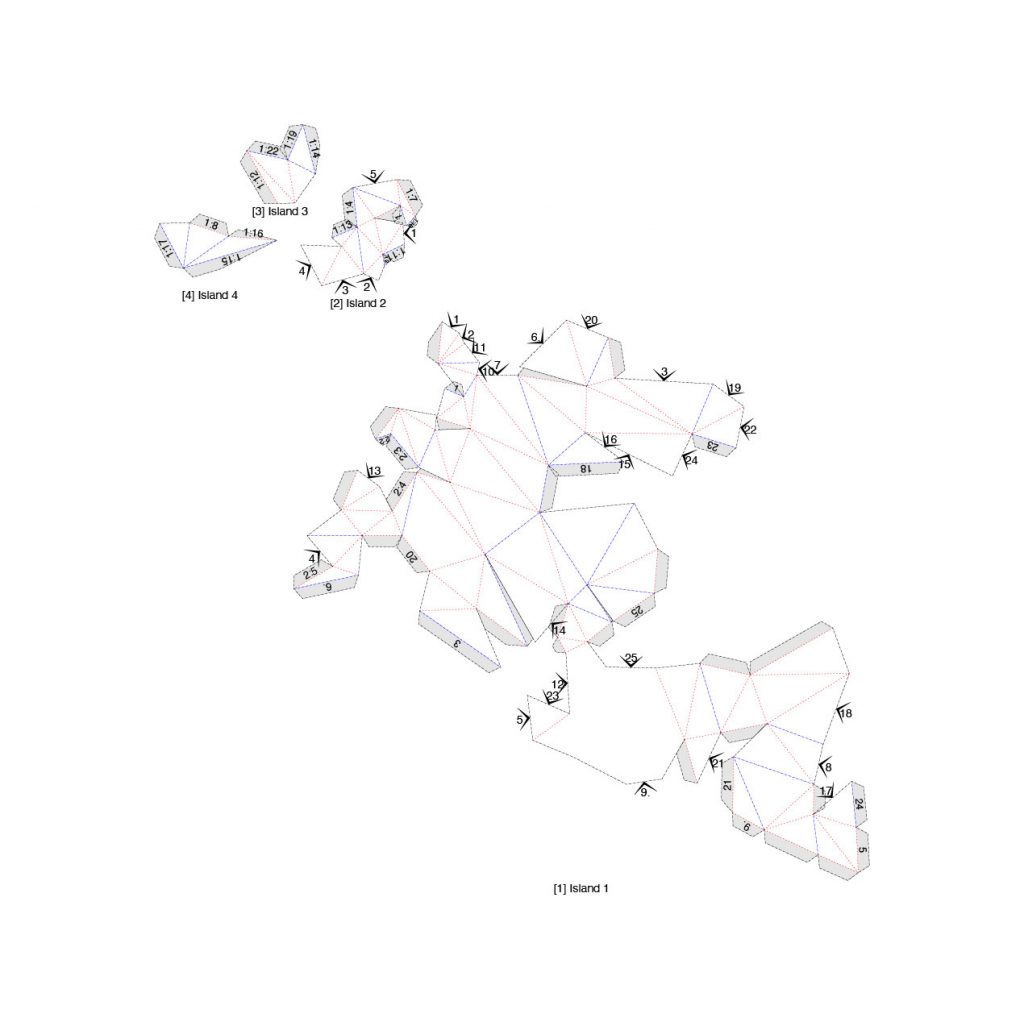

I used tools in blender to simplify and unwrap a model of a dog into a paper-foldable pattern.

Manipulation

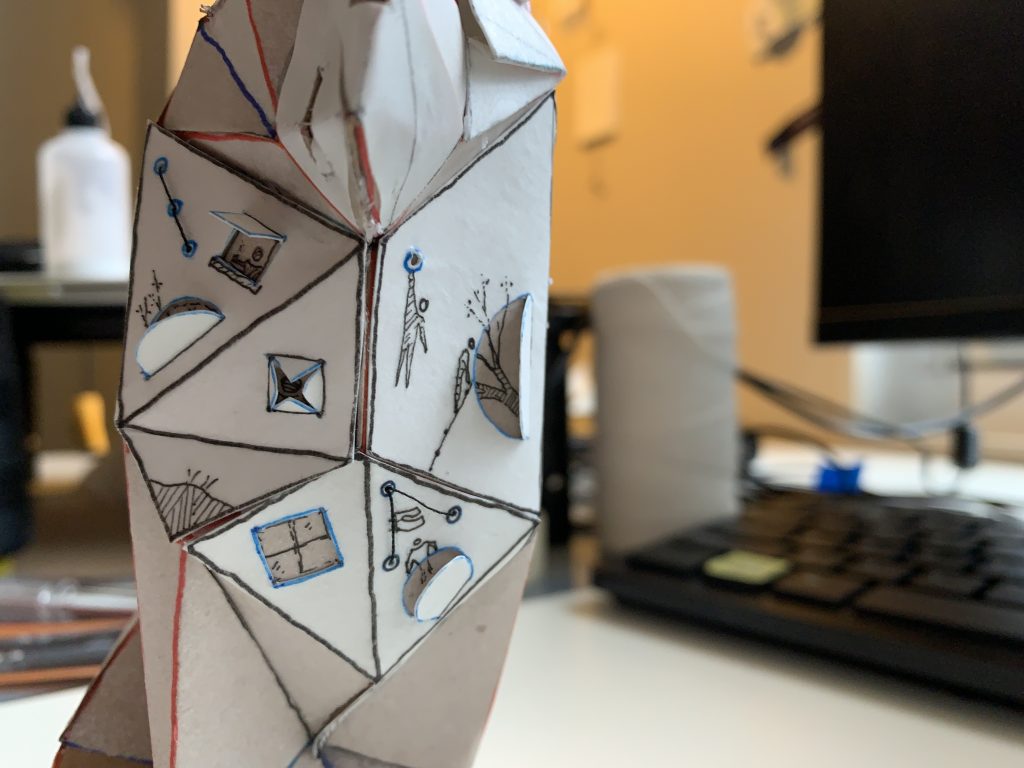

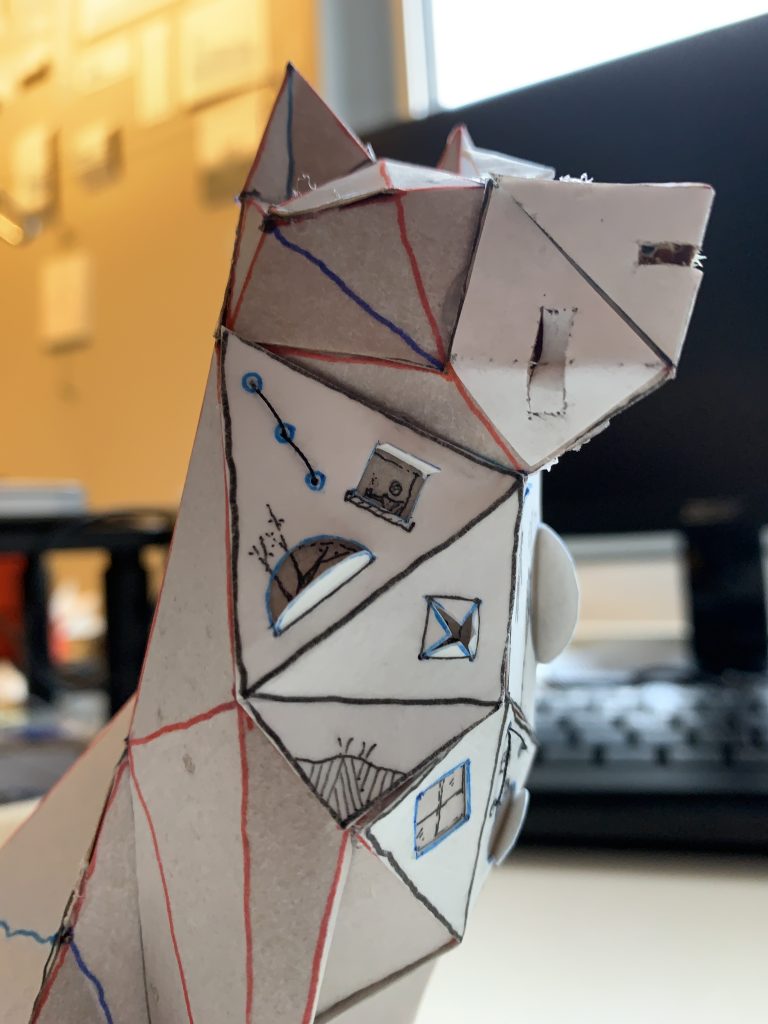

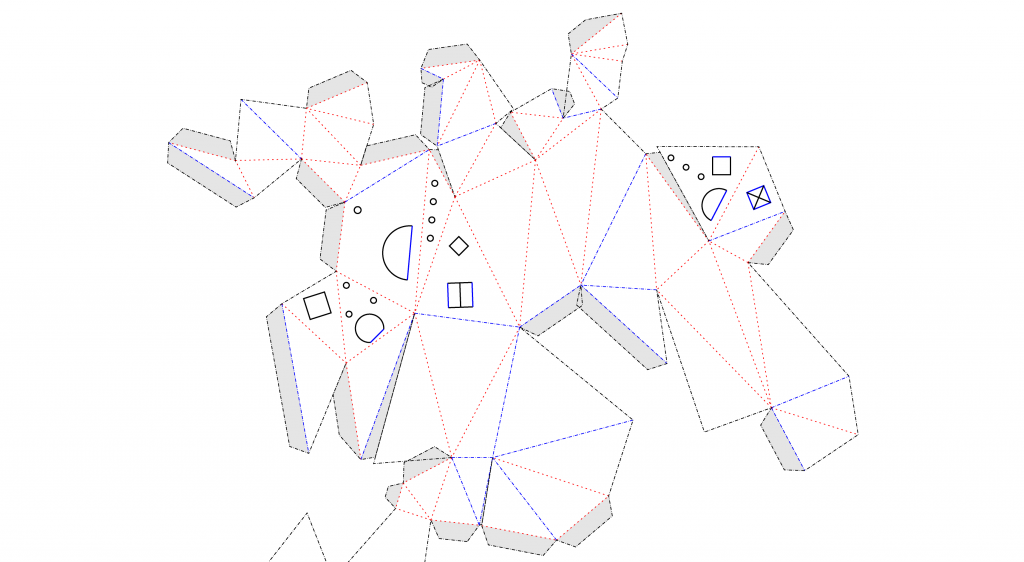

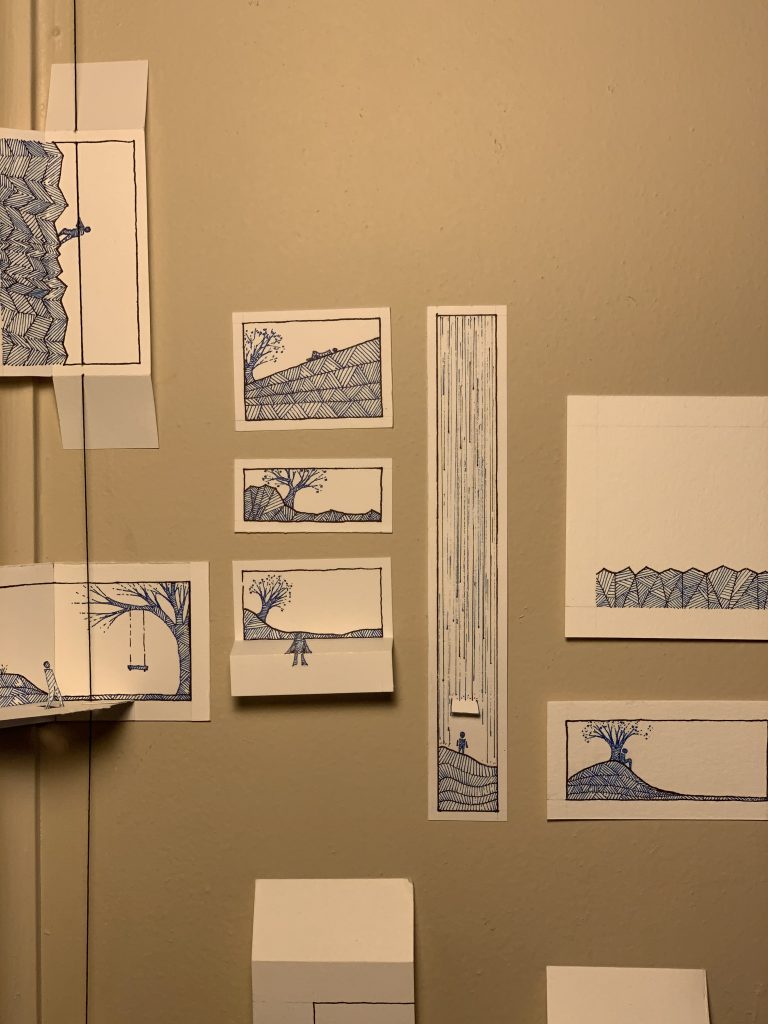

The goal of these manipulations was to create a simple system for playing exquisite corpse with the computer. The computer would randomly place cutting and folding patterns across the flat pattern. I respond by adding 2d illustration that resolve the intention of those folding patterns. For example a folded flap could become a window for a character or a shelf for some books or a crack for grass to grow through.

Randomly Placed Cut & Fold

Illustrations

Reconstruction

This method emerged when I was trying to consider a ‘charming’ way to frame this project, i.e a way to frame the manipulation so that I’d be drawn back to it and excited by it.

Flattening models is integral to the process of applying textures to models, this pipeline inverts that process by flattening the model then generating illustrated texture that responds to the flat pattern.

Lea’s Process

Skinning

I chose a Kitchenaid mixer. This object is an icon of domesticity and is in reality quite heavy and difficult to move (which is why I don’t have it with me in Pittsburgh). When thinking about memories and domestic confinement, I continued to return to the theme of hermit crabs — of repurposing a cast-off object at body scale; of “making do and mending.” I decided to sew a lightweight fabric “shell” of my mixer to inhabit.

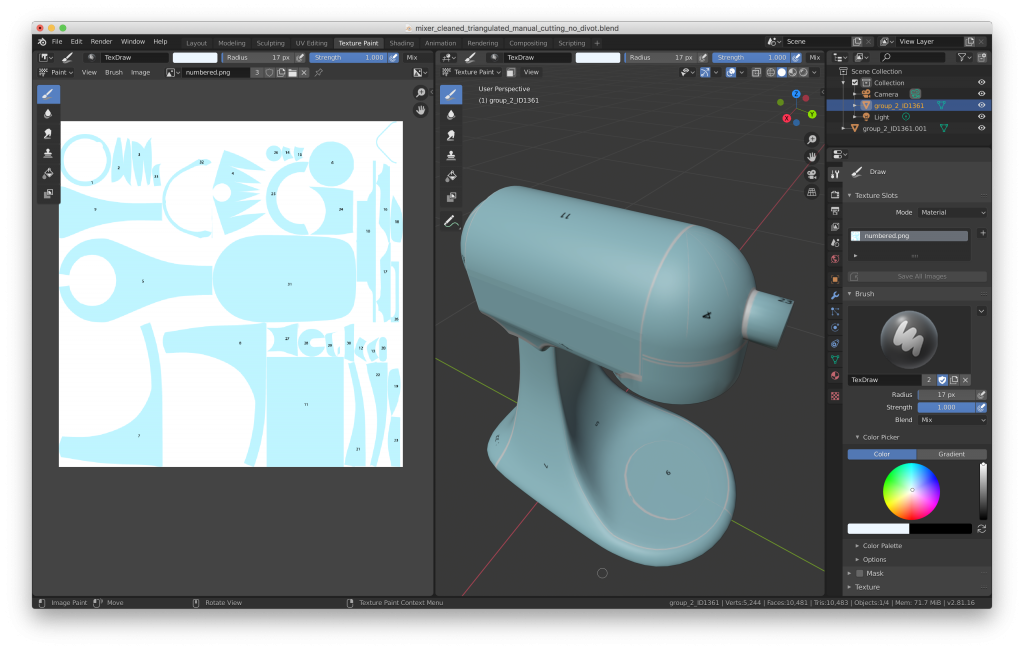

The mixer has smooth curves that felt perfect for cutting as seams; however, my sketchy shareware model file was full of quirks and oddities. I initially planned to use Stein, Grinspun, and Crane’s intriguing Developability of Triangle Meshes code to cut the seams, but the model’s irregularities caused so many problems that by the time I had fixed them, I decided to mark the cut lines on the model in Blender by hand.

This process was very manual, with the result that, by the time I had a nicely carved model, I knew the digital model more intimately than I have ever known the physical one.

Manipulation

I noticed that I really liked the back part of the mixer head, and I would like to use it as a sleeve cap. So I marked that part with UV painting in blender, and unwrapped again. With Illustrator scripting, I wrote a length-aware scale to match the relevant seam lines (marked in red) to the seam length of a known sleeve cap.

Also in Illustrator, I performed a computational “smearing” operation to add pleats. This operation is based on the flat pattern manipulation technique “slash and spread” and it functionally lengthens one seam length while maintaining the others. The lengthened seam can then be pleated or gathered back into its previous length, adding three-dimensional fabric volume.

Reconstruction

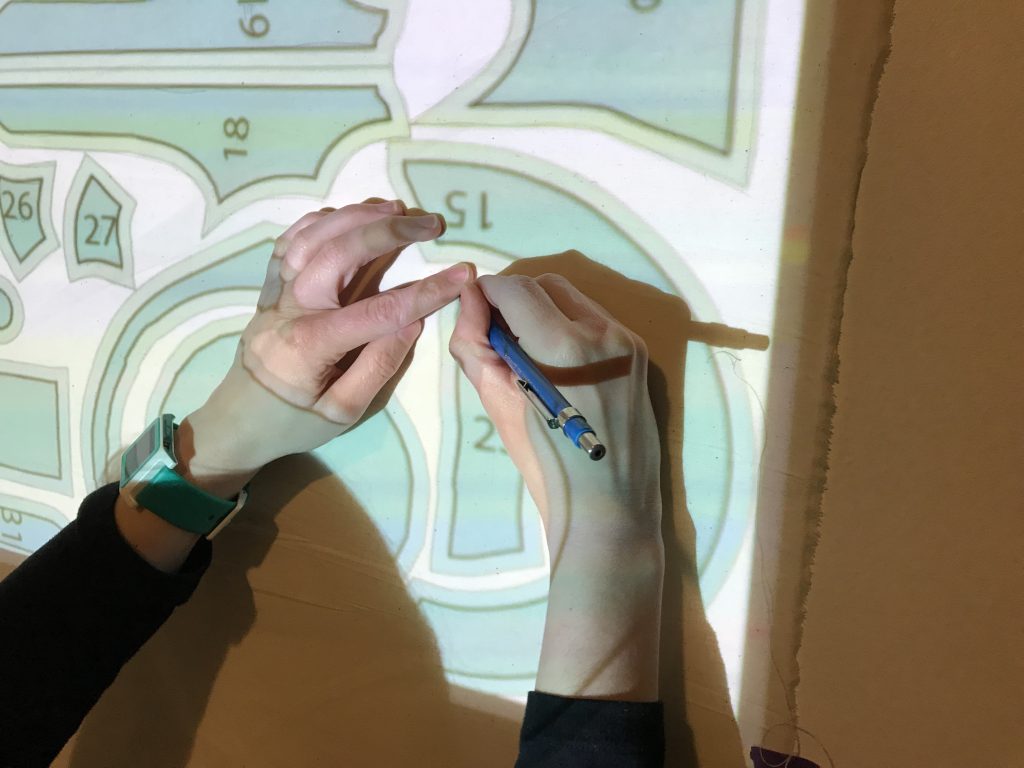

To reconstitute the digital model at body scale, I used a pico projector to project and trace onto fabric. I numbered the parts and referred to the digital model for how to re-assemble them.

System Insights

Sewing has a deceptively simple constraint: you can frankenstein/kitbash patterns together as long as their seam lengths match. This system therefore is one that scales objects by reference to body, via flattening all the way to the one dimension that is seam length: a sort of variational autoencoder for translating from model data to body space.

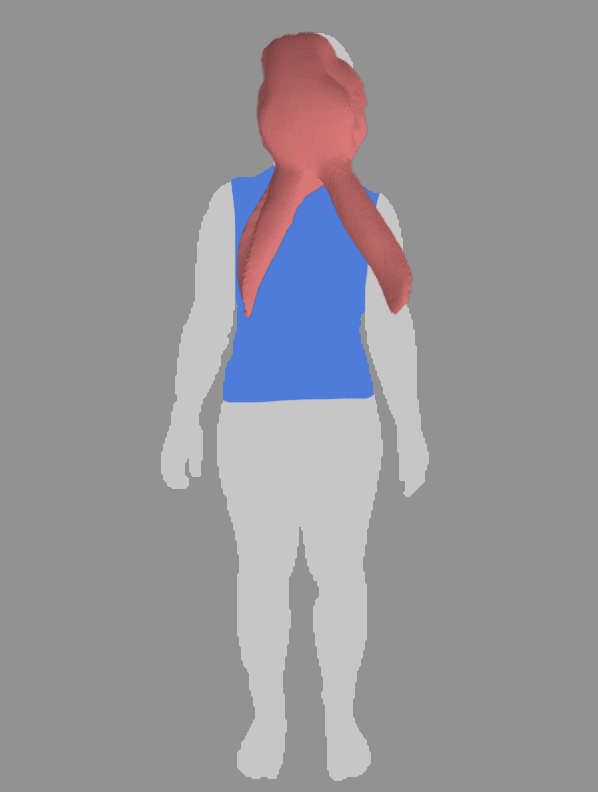

Stanford bunny neck attached to blouse neck

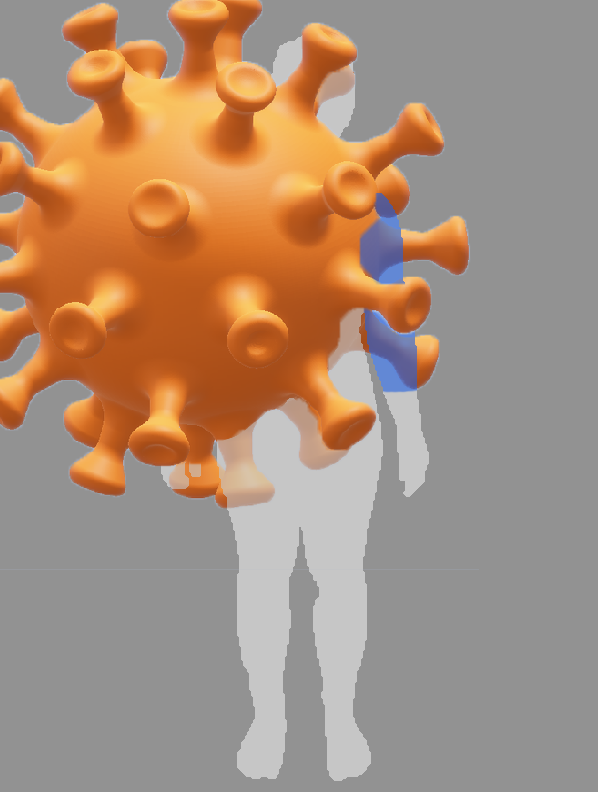

Coronavirus with one spike as a sleeve

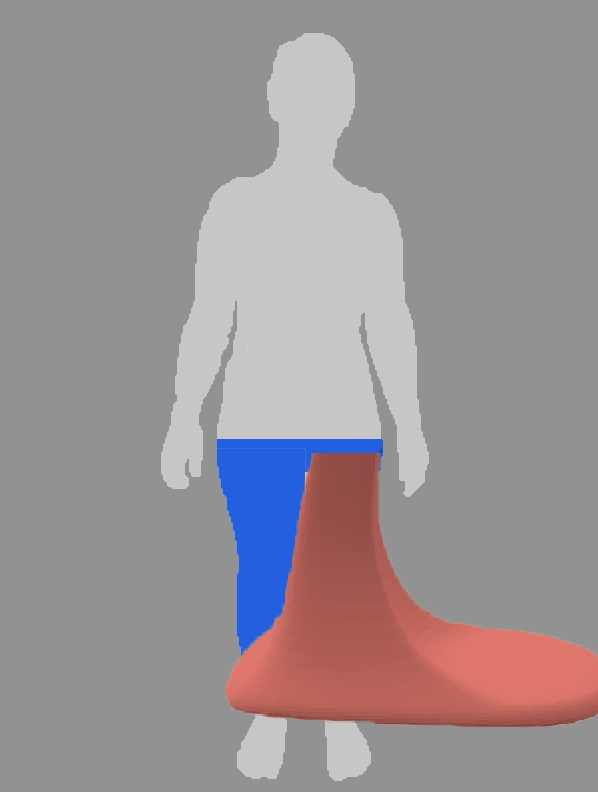

Mixer stand as pants leg

Reflections

Our collection of manipulations explores how the process of digital and craft based deconstruction can expose novel and creative ways of reinterpreting an object.

Many computational processes are about filtering data. This project imagines how a craft person can act a part of a filtering process for 3 Dimensional Data.