“The Entertainment” by Cardboard Computer

|

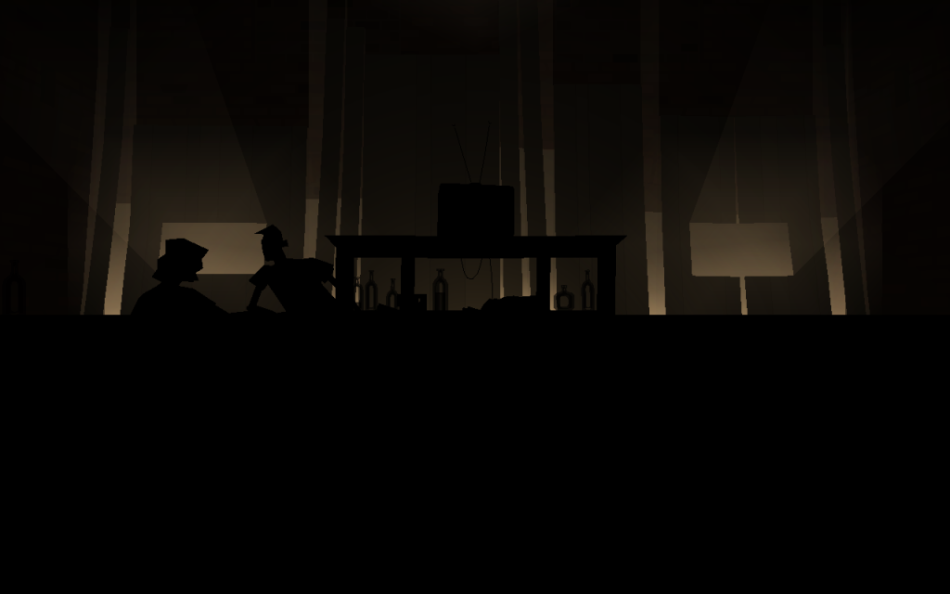

The Entertainment by Cardboard Computer is a piece that inhabits the nearly empty cross section between theatre and video game. Released for free as promotion for the third of five Acts of the studio’s acclaimed Kentucky Route Zero. Taking after their larger project, The Entertainment presents a linear story that interrogates our perception of hierarchical levels of fictionality between separate ontological structures that inhabit the same space. When one talks about theatre, it’s ingrained within our very linguistic pattern to both refer to and perceive a self-contained structure of reality that packages the drama with an isolated ontology that is unable to interact with any system beyond its scope, imprisoned by the fourth wall. The Entertainment attempts to bring this hierarchy of realities into the forefront of our consciousness and ask that we emancipate it in Rancière’s fashion. This theme of blurring roles and realities runs constantly through the piece. It begins innocuously enough, with the player taking on the role of a student actor, who in turn assumes the role of a “Bar-Fly”. The very first seconds of the game loads the player with certain expectations by drawing from the low-level language of video games. The player will see on the screen a representation of three dimensional space, decorated with caricaturized objects representing real objects — furnitures and people, namely, to represent a bar — shown from eye level. Immediately, these are all cues that the modern video game player has been conditioned to recognize. She has already situated herself in the imagined physical space and probably solved the problem of interfacing with an illusory world, moving the mouse across a two-dimensional surface to control the virtual camera angle in quaternion as expertly as if she were moving her own, physical head. This conditioning arose precisely because of how common these cues are within the medium, but what makes it worth reflecting on and presenting it at such a low level in this case is because this conditioning is soon subverted. Disproportionately more than any other medium, video games is a medium that expresses our predilection toward romantic escapism. Though lacking in the humane elements compared to books or film, video games offer far more fidelity as a physical space than any other, which allows the layman to imagine herself within that other space with little to no effort. Yet, just when the player believes she has entered another space as she has done hundreds of times before, the designer of The Entertainment tug away a part of the illusion by revealing that the bar being represented on the screen is, in fact, a verisimilitude of a bar arranged on a theatre stage in the spirit of Magritte: “This is not a bar”. The player’s avatar finds himself downstage from the bar, situated between the play and the audience, whom the player can see. The extent of the player’s interaction amounts to looking certain objects to cause informative text to appear on screen, or to serve as a cue for the play to continue. Eventually, even this modest degree of agency is taken away, as the show goes on regardless of the player’s gaze. Looking to the stagehand will yield factoids about the show. A student company has decided to produce two plays by a playwright Lem Doolittle simultaneously: one pantomime called “The Bar-Fly” which the player’s avatar alone acts out and another Southern Gothic play called “A Reckoning”, both backdropped by a bar setting. Through reading the dialogue boxes, the player learns that the script of “A Reckoning” was written with virtually no stage direction to allow the actors as much agency in shaping the play as the writer and so transfigures into a “Living Script”. The script of “The Bar-Fly” can be seen by looking that the table at the correct moment. It consists of a set of highly specific stage instructions, going so far as to dictating the character’s mental state that doesn’t physically manifest itself. Juxtaposed, they serve as ideological foils that problematize binary notions of activity and passivity with relation to a particular structure of reality, bringing into question the adequacy of how we typically think about our relationship to them. In embodying the ontology of three people, Bar-Fly, a student actor, and her real identity, the player becomes at once a passive observer of events that occur at the bar as Bar-Fly, an active participant in the play as a student actor, and a combination of both as an observer-participant of the entire virtual universe. Yet, even these identities are problematic, as the player also becomes the lone participant of the world of “The Bar-Fly” in playing out a pantomime whose directions are literally unobservable to anyone but the actor/Bar-Fly hybrid, Bar-Fly is the most active member of this universe of one. As both a student actor and player, one looks both within and without different levels of the fourth wall by peering at the virtual audience. And what about those other student actors playing out their part? Thematically, “A Reckoning” deals with how circumstances affect moral decisions; the bartender lies and ultimately sells his patrons to the devil to clear off a debt, and another character abandons her life to flee from the debt that her parents have accrued. As characters inhabiting the constructed world of the play, the audience from any other level likely suspends disbelief that these characters hold free will, even when the narrative portrays how this very will is curtailed. However, from another perspective, their fate is preordained by forces outside of “A Reckoning”, namely by Doolittle’s script and the production. Within the scope of The Entertainment’s universe, these actors hold the greatest agency as the co-authors of the “Living Script”, but the ultimate irony lies in the fact that these characters, too, play out their parts exactly as dictated by the game’s designer. These characters have no agency, nor are they even people at all. First looking to the audience will yield this quote from Antonin Artaud, “We have the right to lie”, though, ironically, the game’s approach is arguably more Brechtian. This simple statement becomes imbued with so many different meanings that it almost becomes meaningless in a post-structural sense. “We” can refer to the designers themselves who built this fictional universe. It can refer to the student production that created another fictional universe within. It can refer to characters in the play who cheat each other. These hints toward an uncertain web of ontology reach a climax at the last few seconds of the game and play when the devil arrives to collect his prize. However, he appears to materialize out of nothing, projecting an otherworldly, electric aura, confronting the player with the possibility that this is no actor playing the part of the devil, but the actual devil himself. If they had not been critical of it already, it definitely jars whatever metaphysical structure the player constructed to justify an escapism from its foundation. Many questions linger — is it the devil or an actor, can the audience see this character, and is this character aware of the audience? The answer, of course, is that there is no answer. The questions are ill-formed from their presupposition that the character, the audience, the player, the actor are all meaningful designations in an ontologically coherent reality. And with the inner realities pushed to their boundaries and bleeding through, the designers got to work deconstructing its hierarchical relationship with our own reality. Throughout the game, the player learns more about the stage production and views the many critical reviews of the play, and is led question whether the entire game is actually a reenactment to some point of a real production, taking place November 16, 1973. The answer again, remains steadfastly ambiguous, not in small part by the developers’ intentional sabotage. Any research into the name Lem Doolittle inevitably leads to a mention of the game, but without an answer to whether Doolittle was an obscure playwright advocated by the game or a fictional character from the start. Their treatment of the play’s supposed set designer, one Lula Chamberlain, is even more interesting. Her identity as an obscure, avant-garde installation artist stretches over multiple realities. She appears as a minor character in both The Entertainment and Act 3 of Kentucky Route Zero, but serves as the focus of another video game short Limits and Demonstrations. The latter depicts a Lula Chamberlain retrospective within a virtual space, where the primary mechanical interaction with the space is in choosing how to respond to the works. This exhibit was recreated by a small collective known as Little Berlin in October 2013 and shown alongside the game. It still remains an open question as to whether Chamberlain refers to a real artist. One of the reasons that the intersection between theatre and game is so sparse is laid bare by The Entertainment. Video game and theatre too often come baggaged with expectations that appear irreconcilable. One can occur at any time and place with no one but a user with a computer, the other requires particular timeslots at specific venues and trained actors. Games demand active participation structured in a language unique to games as a decades-old industry, and the other borrows from millennia-old standards of etiquette and ethos. By juxtaposing them, the developers ask that we question our normative way of thinking about both media. Do away with conventional notions of participation, spectacle, and fictionality to expand one’s experience at a conceptual level. Lula Chamberlain’s Edit of Nam Jun Paik’s “Random Access” |