Philosopher Vilem Flusser said, “We do not think about the act of writing while writing, but about what we are writing.”

We understand writing as a form of art that comes directly from soul to page, an intimate reveal of human emotion.

This core concept of writing is complicated with the development of AI trained to write and write creatively. It is, of course, “thinking” about the act of writing while writing, and doesn’t really have the capacity to think about what it is writing in Flusser’s sense.

AI writing models present a challenge to our notions of writing, but they may also be an overlooked tool to writers themselves. What do they mean for writers and the craft in the future? Could a robot write a New York Times Bestseller?

A friend of mine recently reached out to me and asked if I would be willing to contribute a poem to a zine they were making with digital artists. They told me to write anything under the thematic umbrella of “Fluidity”. I wrote a very unstructured poem about my past and present constantly flowing into one another. Later, I was playing around with a Writing AI app called Inferkit, and I decided to see whether it would pick up on the idea of fluidity and motion if I fed it some lines of my poem. I gave it the first and last line of each stanza, and let it fill in the middle. The result: Not only did it capture the theme of “fluidity”, but it used a few choice words that I had used and did not feed it. To my surprise, it also picked up a level of plot and incorporated an entire last stanza involving turning into something else–eerily similar to my original. I was curious: Does this speak to my lack of originality as a writer, or is it a testament to the growing sophistication of Natural Language Processing and other AI writing mechanics?

Natural Language Processing, GPT-3, & Its Uses:

Human language is not an easy thing to teach a machine. We have tone variances, we are able to understand that “she” is someone specific and variable, we understand that “bear” is an animal and “London” is a place. We also understand the feelings that accompany the words we choose. These are some of the challenges AI confronts when learning natural language. Most AI that has learned to write, speak, or communicate in any human language is built on what’s called Natural Language Processing. Natural Language Processing (NLP) is the utilization of vast amounts of language material, organized and structured for the AI to understand, to try and train artificial intelligence to speak or write in an organic, natural way. It is what informs chatbots, Google Maps, Google Translate, Siri, and Speech-to-text. Most of us interact with NLP systems in some way every day.

One NLP AI system is GPT-3. GPT-3 was developed by Open AI, and is the latest and more sophisticated model used by a variety of platforms. Its learning comes from all corners of the internet, so it is trained on anything from novels, to blog posts, to ads, to Facebook comments. It is sophisticated enough to write entire news articles that are mostly indistinguishable from human writing. The eerie video of two robots talking with each other about what it means to be human is also GPT-3. Many of the creative writing AI apps are powered by this, and the sophistication of GPT-3’s language knowledge is what allows users to customize the tone, add characters, and build a story conjointly with the AI. The wide implementation of GPT-3 doesn’t come without its criticism. Controversies have arisen surrounding its use of racially inflammatory language outputs likely learned from biases on the internet, and also for its environmental impact.

Xiaoice

Another Natural Language Processing model, perhaps the most famous one, is Microsoft’s Xiaoice. First developed in 2014, Xiaoice has become a celebrity, poet, news personality, and highly personal chatbot. Extremely popular in China, she has long-standing relationships with many of her users. Built on an “empathic computing framework”, Xiaoice is especially good at having real, emotional conversations with her users, creating a network of millions of fans. Xiaoice’s poetry was circulating online before anyone knew that AI had written it, and she wrote the first AI-authored published book of poetry, “The Sunlight and the Lost Glass Window”. Naturally, many poets disapproved of the work and felt it may mark the beginning of the desolation of the art form altogether. They contend that a machine that has never been alive could never capture human emotion poetically. Xiaoice’s intimate relationships with her users might attest otherwise.

Comparison of a few AI Writing (Free) Programs

To learn a bit more about how the free creative writing apps generate content, I decided to test out a few. I primarily wanted to see their ability to pick up on style, tone, and plot. The main tools I used were Inferkit and Sudowrite. I did play around with some others, like Sassbook and Ryter which is primarily configured to help write articles and could not pick up on poetry format.

Examples

I fed Sudowrite the first four lines of the Mary Oliver poem, “Wild Geese”, and let it do its thing. Here is the comparison between Sudowrite and the actual poem. The purple text notes where my typing ends and Sudowrite’s additions begin.

Sudowrite repeated the “Soft animal of your body” quite a bit, but it did pick up on the poem’s general theme of finding joy and acceptance in life.

Here are the results of the same poem input using Inferkit.

Inferkit seemed to prefer shorter lines, and auto-generated the next words of the actual poem, “Tell me about your despair.”

As I tried out these platforms with various writings other than my own, I noticed that if a work was particularly popular (and likely appearing on the internet more often), the AI already knows the next few lines. Both Sudowrite and Inferkit gave me the exact next paragraph when I was using Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone.

Here is an example of Sudowrite given an excerpt from Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower.

In this example, Sudowrite picked up on the idea of injustice that runs through the novel, as well as the main character’s feelings towards it.

Here is Inferkit with the same excerpt:

It seems in this example that Inferkit is writing this as a news piece or blog article about a current event, rather than a story plotline. These examples are specifically surrounding free applications of AIs automated writing. With access to GPT3 and coding skills, of course, the outputs would be different. I use these examples just to demonstrate the capabilities and shortcomings of these applications and the types of outputs they provide.

Implications in the Craft of Writing

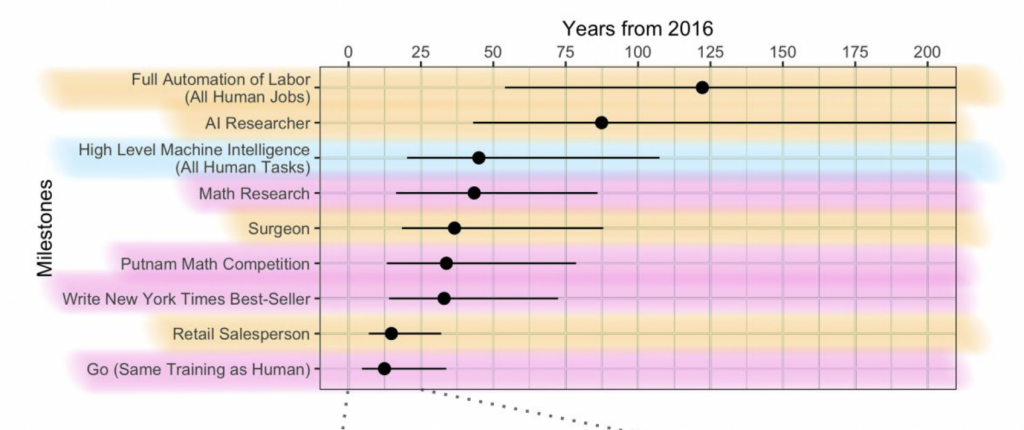

The implications of more sophisticated NLP AI programs like GPT-3 entering the creative writing field are varied. AI Impact’s 2016 Expert Survey on Progress in AI asked about predictions of AI’s progress in the future surrounding specific tasks. For the task “write a New York Times Bestseller”, researchers estimated a 25% likelihood of it occurring in the next 20 years and a 62.5% likelihood within the next 50 years. This is around the same time frame they gave to “surgeon”, and is a significantly lower probability than the task “retail salesperson”.

We often center our conversations about creativity and AI around whether or not it can become “human enough” to replace us or to solve human problems without us. One writer called AI-generated writing “A deepfake of meaning itself.” What if instead of suffering over the thought of Barnes and Nobles being full of robot books, we thought about AI as an implement to enhance our art?

The relationship between humans, machines, and creative writing is not necessarily a new one. Alison Knowles created a poem called “House of Dust” using an IBM computer programming system called FORTRAN in 1967, and used one of the stanzas as inspiration for a large-scale sculpture. K Allado-McDowell co-wrote the novel Pharmako AI with GPT-3 in 2020. In both of these instances, artist and machine were in collaboration with the transformative nature of unpredictability provided by the AI. A study that asked writers to co-write with a “machine-in-the-loop” setup, meaning the AI plays a supporting role to the person’s inputs, found that those who wrote with the machine were more satisfied with the end result than those that wrote it without.

AI may have the capability to profoundly affect the way we think about the act of writing moreso than the livelihood and paychecks of creative writers themselves. Of course, disruption of the creative traditions of a practice can provoke quite a bit of resistance (take Jackson Pollock’s early criticism, for example).

Creative writing has long been a uniquely solitary act, the most substantial collaboration being with inspirations from past writers. We think of writers on retreat in a cabin in the woods, isolated while perfecting their craft. The idea of solitude as a necessity for becoming “self-forgetful” in order to achieve elevated creativity is, in many ways, something AI can give to a writer.

Allado-Macdowell said on his process writing Pharmako AI, “At the end of the process, I felt more like I’d been divining, spelunking, or channeling than writing in a traditional sense.” Partnerships between writer and AI can generate serendipitous moments of creative gesture that allow a writer to break through writer’s block, and create unforeseen plots and descriptions. It can also push the writer outside their own imagination and lived experiences, just as that isolation can distort their sense of self.

Other Implications

Plagiarism Issues

The implications of more sophisticated NLP AI programs like GPT-3 entering the creative writing field are varied. With writers using AI as a collaborative tool, a critical potential issue is plagiarism. This topic has mostly been discussed through the lens of academic integrity, but there are parallel issues within creative writing. As mentioned earlier, inputting Harry Potter excerpts prompted word-for-word outputs from the book. A writer using platforms such as these could unintentionally be using full lines of writing by someone else.

And using a model that is trained on millions of pieces of writing, it may be difficult to discern what is random and what might be pulled from another source. In the cases of writers like Allado-Macdowell and Knowles, they were actually coding and training the machines, and more able to control the funnel of information that was going in and coming out. Those who don’t have the technological skills to train the machine themselves may opt to use programs like Inferkit and Sudowrite, where dangerous potentials could arise.

“There are no laws for the novel. There never have been, nor can there ever be.”

Doris Lessing

AI might just change the laws of the novel. For now, a fully independent AI-written novel likely won’t be on the NYT bestseller list anytime soon. But maybe it’s time to consider letting AI into the practice.

References:

AI Impacts. “2016 Expert Survey on Progress in AI,” December 14, 2016. https://aiimpacts.org/2016-expert-survey-on-progress-in-ai/.

The Guardian. “A Robot Wrote This Entire Article. Are You Scared yet, Human?,” September 8, 2020, sec. Opinion. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/sep/08/robot-wrote-this-article-gpt-3.

Clark, Elizabeth, Anne Spencer Ross, Chenhao Tan, Yangfeng Ji, and Noah A. Smith. “Creative Writing with a Machine in the Loop: Case Studies on Slogans and Stories.” In 23rd International Conference on Intelligent User Interfaces, 329–40. Tokyo Japan: ACM, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1145/3172944.3172983.

“Demo – InferKit.” Accessed February 14, 2022. https://app.inferkit.com/demo.

People’s Dialy Online. “First AI-Authored Collection of Poems Published in China – People’s Daily Online,” May 31, 2017. http://en.people.cn/n3/2017/0531/c90000-9222463.html.

Flusser, Vilém. “The Gesture of Writing.” In Gestures, 208. University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

Hoel, Eric. “I Got an Artificial Intelligence to Write My Novel.” Electric Literature (blog), June 10, 2021. https://electricliterature.com/i-got-an-artificial-intelligence-to-write-my-novel/.

Plagiarism Today. “How AI Will Change Authorship and Plagiarism,” February 12, 2019. https://www.plagiarismtoday.com/2019/02/12/how-ai-will-change-plagiarism/.

Literary Hub. “How Collaborating With Artificial Intelligence Could Help Writers of the Future,” November 9, 2021. https://lithub.com/how-collaborating-with-artificial-intelligence-could-help-writers-of-the-future/.

IBM Cloud Education. “What Is Natural Language Processing? | IBM,” July 2, 2020. https://www.ibm.com/cloud/learn/natural-language-processing.

“Jackson Pollock Criticism Rebuted by Helen Harrison – The New York Times.” Accessed March 3, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2010/12/05/nyregion/05spotli.html.

Kantosalo, Anna, and Sirpa Riihiaho. “Quantifying Co-Creative Writing Experiences.” Digital Creativity 30, no. 1 (January 2, 2019): 23–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/14626268.2019.1575243.

Loutfi, Amira. “12 Artificial Intelligence Tools to Write Your Novel For You.” MetaStellar (blog), October 18, 2021. https://www.metastellar.com/2021/10/18/12-artificial-intelligence-tools-to-write-your-novel-for-you/.

“Next Chapter in Artificial Writing.” Nature Machine Intelligence 2, no. 8 (2020): 419–419. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-020-0223-0.

OpenAI. “OpenAI.” Accessed February 28, 2022. https://openai.com/.

Rogers, Hannah Star. “Cheering Artificial Intelligence Leader: Creative Writing and Materializing Design Fiction.” Leonardo 53, no. 1 (n.d.): 58.

Rytr. “Rytr · Best AI Writer, Content Generator & Writing Assistant.” Rytr. Accessed February 24, 2022. https://rytr.me.

“Sassbook AI Writer: High-Quality AI Text Generator.” Accessed February 24, 2022. https://sassbook.com/ai-writer.

Schmelzer, Ronald. “What Is GPT-3? Everything You Need to Know.” SearchEnterpriseAI. Accessed February 22, 2022. https://www.techtarget.com/searchenterpriseai/definition/GPT-3.

Spencer, Geoff. “Much More than a Chatbot: China’s Xiaoice Mixes AI with Emotions and Wins over Millions of Fans.” Microsoft Stories Asia, November 1, 2018. https://news.microsoft.com/apac/features/much-more-than-a-chatbot-chinas-xiaoice-mixes-ai-with-emotions-and-wins-over-millions-of-fans/.

TWiT Tech Podcast Network. Microsoft’s Xiaoice Bot Is Getting Smarter, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P8tEB0W9YnM.

Weller, Chris. “Chinese Poetry Scholars Are ‘disgusted’ by a New Book Written by a Robot.” Business Insider. Accessed February 28, 2022. https://www.businessinsider.com/chinese-poetry-written-by-robot-2017-6.

“Why Writers Need Solitude. Writing Takes Extraordinary Persistence… | by Jan Fortune | Medium.” Accessed March 3, 2022. https://janfortune.medium.com/why-writers-need-solitude-f5e9bd93b17a.

Wilk, Elvia. “What AI Can Teach Us About the Myth of Human Genius.” The Atlantic, March 28, 2021. https://www.theatlantic.com/culture/archive/2021/03/pharmako-ai-possibilities-machine-creativity/618435/.

Tech2. “XiaoIce Is the AI Chatbot That Millions of Lonely Chinese Are Turning to for Comfort- Technology News, Firstpost,” 13:53:37 +05:30. https://www.firstpost.com/tech/news-analysis/xiaoice-is-the-ai-chatbot-that-millions-of-lonely-chinese-are-turning-to-for-comfort-9910921.html.