Recent years have seen a rise in the number of artistic and cultural institutions that offer virtual experiences. The appeal of these alternatives to in-person attendance seems to have increased since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Google Arts and Culture provides a mass landing space for those looking to both experience culture in a virtual setting, and engage with different forms of art in a different way. This post looks at the history of the website/app, its noteworthy features, and the implications of this platform—and others like it—for artistic and cultural organizations.

What is Google Arts and Culture?

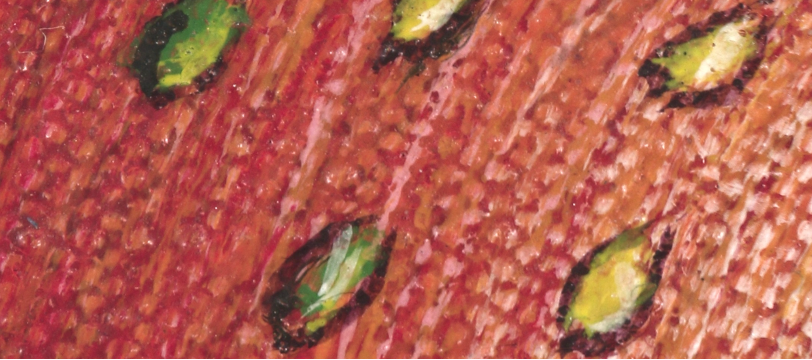

Launched by Google in 2011 as a nonprofit initiative, Google Arts and Culture was created with the purpose of increasing the accessibility of art and culture. The platform describes itself as a new way of experiencing art and culture, with the main attraction being that the user is able to access various types of art regardless of the their location, or the location of an institution. The platform currently has over 2,000 global partners and over 100,000 works of art, giving museums, performing arts venues, and historical landmarks the ability to showcase various exhibitions, photographs and information about their institutions. Some prominent institutions include The British Museum, The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and the Sydney Opera House. When an institution becomes a partner, they obtain access to tools that allow for paintings and other materials to be digitized and uploaded to the platform. The Art Camera, which performs the digitization, is a high-resolution camera that allows for users of the platform to zoom in and observe up-close details.

Another digitization feature allows institutions to add virtual, 360 degree tours to their pages, similar to a view you would see in Google Maps.

AI, AR, and Experiments

Building off a substantial number of partnerships, Google Arts and Culture utilizes technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI)/machine learning and augmented reality (AR) for a variety of experiments that allow the user to establish personal connections to art, primarily by participating in the creative and art-making processes themselves.

One of the platform’s most prominent experiments is its selfie feature. Using the Google Arts and Culture app, users are able to use selfies to see what piece of art they resemble. When the user uploads their photo, Google’s software works to scan the selfie and go through the variety of paintings in the databases for a potential match. Though created with good intentions, this experiment did not come without controversy. Many BIPOC individuals found that when they used the feature, their results did not come with the same depth as those of White individuals; the works of art that displayed people of color were already limited, and when they were matched, it was often with figures that displayed “stereotypical tropes.”

This is not a unique instance of artificial intelligence reflecting human biases; Google as a larger enterprise—along with the artificial intelligence industry in general—has come under fire for its general lack of diversity. The reproduction of racist stereotypes is not necessarily the algorithm’s fault, but rather the fault of the people behind the algorithm. Some have also acknowledged how the platform’s mishap specifically reflects the lack of diversity in the art world.

In a less harmful way of establishing a personal connection to art, Google Arts and Culture introduced its Pet Portraits feature, which is also utilizes AI. The process is similar to that of the selfie feature: the user takes a picture of their pet, and the algorithm attempts to find an artistic match. AI has also been used for the purposes of preservation. Along with one of their partners, the Belvedere Museum in Vienna, Austria, they utilized machine learning to restore the paintings of Austrian painter Gustav Klimt in color.

Google Arts and Culture also makes prominent use of augmented reality (AR). The video below, uploaded by NASA and displayed on Google Arts and Culture’s website, utilizes AR and allows the user to “fly through a galaxy.”

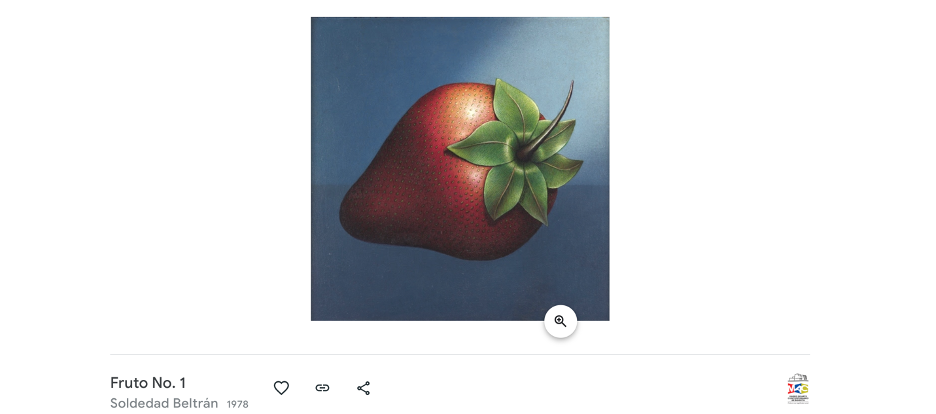

Additionally, using the above painting, Fruto No. 1, I was able to use the Art Projector feature on the app, which lets you see what an piece of art would look like up close.

The leaders behind Google Arts and Culture, and the larger Google Cultural Institute, work regularly to explore and encourage the uses of AI and AR in the art-making process. In partnership with the Barbican Centre in London, a virtual exhibit detailing the “evolving relationship between humans and technology” and its implications for art, culture, and other aspects of our daily lives, is available to users.

Experiments such as the Blob Opera are fun way to receive deeper exposure to certain art forms (in this case, opera). There is also the Assisted Melody experiment, which allows the user to engage in a special music project. The user is able to write their own music, and the machine transforms it to make it sound like that of famous composer. On a different side of the musical spectrum is the Hip Hop Poetry Bot, an AI that was trained on rap and hip hop music, designed as a way to create a deeper appreciation for the art form. In my opinion, experiments such as these play a large part in regards to the access model that is integral to Google Arts and Culture’s platform and offerings.

Disruptions and Implications

A form of disruption that I believe affects the art world is the aspect of personalization. In addition to the variety of AI and AR-based experiments that were mentioned earlier, a user can essentially curate their own art collections without having to leave their homes to do so. Because there are works of art from nearly every segment of the world, you can regularly see works of art that you otherwise might have never seen or heard of.

My initial perception of the Google Arts and Culture platform was that its presence would disrupt the visual arts world more than that of the performing arts. While the platform does showcase performing arts venues such as the Sydney Opera House and the Dance Theatre of Harlem, it is difficult to incorporate the entire experience of attending a ballet or a theatre production in an app such as Google Arts and Culture. At the same time, I still believe that many people visit museums not just to see the art, but to participate in the entire experience of being able walk around the physical building and engage with others who have come for a similar purpose.

To that end, I think that Google Arts and Culture serves more as a supplement, as opposed to a replacement, for cultural institutions. By utilizing the platform, a user is able to have a better idea of what they would like to see and experience if they were to visit the institution in person. In a way, the platform can serve as a marketing tool for partner institutions, as many of them do not publish the entirety of the collections that reside in their physical buildings. For larger artistic and cultural institutions, it could be worthwhile to look into establishing a partnership with the platform. It could also benefit smaller institutions, as your exhibitions and what you have to offer can be put on display for users from all around the world to see.

On the patron end, it allows users and potential visitors to be more informed of what the experience at a particular museum may be like. Because the app and the website are easily accessible, Google Arts and Culture lives up to its purpose of providing a new way of experiencing art, culture, and history: the app and website are both easily accessible, enabling users to engage in and view art whenever they want.

References

“12 Museums From Around the World That You Can Visit Virtually | Travel + Leisure | Travel + Leisure.” Accessed March 4, 2022. https://www.travelandleisure.com/attractions/museums-galleries/museums-with-virtual-tours.

“About Google Cultural Institute.” Accessed March 4, 2022. https://about.artsandculture.google.com/experience/.

“About Google Cultural Institute.” Accessed March 4, 2022. https://about.artsandculture.google.com/partners/.

“AI: More than Human — Google Arts & Culture.” Accessed February 25, 2022. https://artsandculture.google.com/project/ai-more-than-human.

“Assisted Melody by Simon Doury, Artist in Residence at Google Arts & Culture Lab with Google Magenta – Experiments with Google.” Accessed February 25, 2022. https://experiments.withgoogle.com/assisted-melody.

Bustle. “Google’s ‘Arts & Culture’ App Is Being Called Racist, But The Problem Goes Beyond The Actual App.” Accessed February 25, 2022. https://www.bustle.com/p/googles-arts-culture-app-is-being-called-racist-but-the-problem-goes-beyond-the-actual-app-7929384.

Google. “Exploring Art (through Selfies) with Google Arts & Culture,” January 17, 2018. https://blog.google/outreach-initiatives/arts-culture/exploring-art-through-selfies-google-arts-culture/.

“Google Used AI to Recreate Gustav Klimt Paintings Burned by Nazis.” Accessed February 25, 2022. https://mashable.com/video/gustav-klimt-ai-paintings-google-arts-and-culture.

Google. “How Artists Use AI and AR: Collaborations with Google Arts & Culture,” May 24, 2019. https://blog.google/outreach-initiatives/arts-culture/how-artists-use-ai-and-ar-collaborations-google-arts-culture/.

“Google Arts & Culture.” Accessed February 25, 2022. https://artsandculture.google.com/.

Google Arts & Culture. “Art Camera.” Accessed March 4, 2022. https://artsandculture.google.com/project/art-camera.

Google Arts & Culture. “Blob Opera.” Accessed March 4, 2022. https://artsandculture.google.com/experiment/blob-opera/AAHWrq360NcGbw.

Google Arts & Culture. “Fruto No. 1 – Soldedad Beltrán.” Accessed March 4, 2022. https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/fruto-no-1-soldedad-beltrán/pgHEHsf8R2zbCg.

Held, Amy. “Google App Goes Viral Making An Art Out Of Matching Faces To Paintings.” NPR, January 15, 2018, sec. America. https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2018/01/15/578151195/google-app-goes-viral-making-an-art-out-of-matching-faces-to-paintings.

“Hip Hop Poetry Bot by Alex Fefegha in Collaboration with Google Arts & Culture – Experiments with Google.” Accessed February 25, 2022. https://experiments.withgoogle.com/hip-hop-poetry-bot.

Metz, Cade. “Who Is Making Sure the A.I. Machines Aren’t Racist?” The New York Times, March 15, 2021, sec. Technology. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/15/technology/artificial-intelligence-google-bias.html.

Muriuki, Purity. “What Is Google Arts & Culture?,” July 17, 2021. https://startup.info/what-is-google-arts-culture/.

NASA Video. Orion Nebula – 360 Video, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1-goEmM0c4Q.

“Pet Portraits — Google Arts & Culture.” Accessed March 4, 2022. https://artsandculture.google.com/camera/pet-portraits.

Schofield, Matthew. “LibGuides: Advanced Google: Google Arts and Culture.” Accessed February 25, 2022. https://library.sfc.edu/Google/artsandculture.

“Sydney Opera House, Sydney, Australia — Google Arts & Culture.” Accessed March 4, 2022. https://artsandculture.google.com/streetview/sydney-opera-house/KgGPW2YWtcHpBg?sv_lng=151.2135034733324&sv_lat=-33.85845058282505&sv_h=30.36855573629456&sv_p=2.382047067182725&sv_pid=opBj2MqN2Mk4yX5QdZPYDw&sv_z=1.

TechCrunch. “Why Inclusion in the Google Arts & Culture Selfie Feature Matters.” Accessed February 25, 2022. https://social.techcrunch.com/2018/01/21/why-inclusion-in-the-google-arts-culture-selfie-feature-matters/.