Museums ranging in all disciplines act as cultural hubs that narrate a story to their visitors. These spaces, and the people who curate the items that are found in these spaces, in many ways dictate the cultural identity of the respective area they exist in. The items acquired by museums often have great cultural significance or they represent cultural significance. These items freeze a moment in time and bring with it the mood, themes, implications, successes, and failures of the respective period. Because of this it is the responsibility of these museums to respect these artifacts and keep them safe so that these small snippets of time can be digested by those who seek out stories.

In the United States, the American Alliance of Museums holds the “AAM Code of Ethics for Museums” that accredited museums follow.1 The “AAM Code of Ethics for Museums” exists to make sure that all museums in the United States are acting with integrity.2 Specially, the code details how museums should acquire, own, have on loan, and store the items in their collections. The “Collections” section of the document protects “[…] objects, specimens, and living collections representing the world’s natural and cultural common wealth”.3 Art in this case is classified as an object, and digital art falls under this category as well. However, because digital art exists as a different media and in a different space than “traditional” art, museums need to acquire, store, and care for this art in a new way while still following the code.

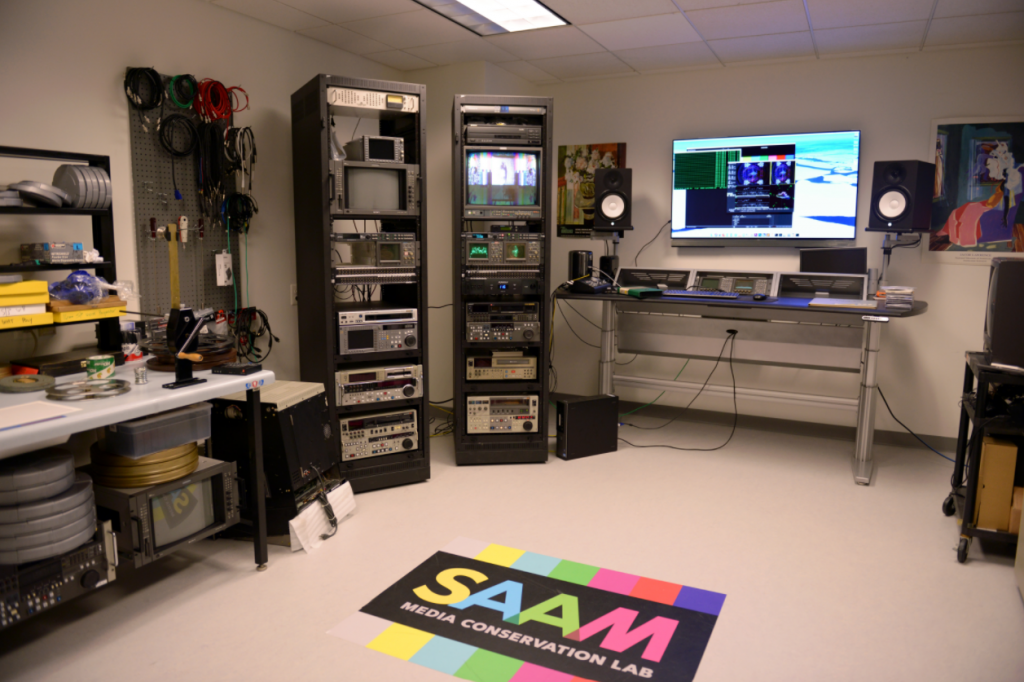

The acquisition process is the first step in a museum gaining a new permanent or on loan item for its collection. Just like any “traditional” art the museum would need to gain some beginning attributes to know what they are acquiring. In the case of digital art, a museum needs to do this as well, but with some additional steps. The Museum of Modern Art teaches that museums need to gain a “brief technical history” as well as the “equipment requirements” a museum would need to display the digital art.4 Knowledge of the supplies and instruction to install digital artwork is vital, because many in-house gallery managers may have never installed this respective digital art before.5 Similar to installation art, digital art can have many different installation methods that are unique to the artist and the art. Continually, to protect the rights of the artist the museum needs to obtain comprehension of the stipulations of ownership that the museum is gaining with the work.6 If the digital art is not the only one of its kind than this could affect the rights that a museum has to name and artwork itself.7 Moreover, the artist may only be selling the museum the method and instructions of creation and not the actual work they created, which changes the way the museum can credit and display the piece.8 At some point in the acquisition process the archival and conservation departments in the museum need to be involved in the conversation in order to assess how the digital art will be able to exist in the museum.9 The storage, care, and archival needs of each digital art piece will be different, and therefore these departments are vital to understanding if the museum can take on a piece with these respective specific needs. Specifically, a digital artwork requires a particular equipment piece to view the art.10 Hence, the museum would also potentially need to acquire this equipment, store, and archive it.11 In this case the equipment is not a part of the art, but it is essential to the way the artist intends the art to be experienced.12

Once the museum has the art they need to care for and conserve the art. Just like oil paintings that have parameters about how it needs to be cared for in order to survive, digital art also requires specific measures to insure it lasts across time. Unlike oil paintings however, at this point museums and museum authorities have not dictated a formal procedure for the management of digital objects.13 Continually, every art museum holds different collections with a number of different mediums within that collection, so the needs of each museum are vastly unique.

When museums first began adding digital art to their collections it meant that their whole space needed to be rethought to accommodate a new medium. Jim Coddington, who works in conservation at the Museum of Modern Art, sought out to answer initial questions of how museums can make this art last.14 Coddington discusses the experimentation process at the Museum of Modern Art in 2003, “Over time we drafted a series of projects, each one becoming slightly larger, each one inviting new expert voices to the discussions. We started with—what else? —a collection survey”.15 From the initial trials of 2003, Coddington continues to note that housing digital art in a museum is dynamic and above all a multi-department effort from acquisition of the piece.16 More recently in 2016 when the Museum of Modern Art was acquiring Bouchra Khalili’s The Mapping Project, Coddington notes the process “[…] involved the collaboration of curators, conservators, registrars, audio-visual technicians, and exhibition designers”.17 Specifically, when it comes to conservation of art Coddington poses that the future of this practice may see a change that enduring.18 He states, “We are becoming less dogmatic, less rules-based in our approach, and more risk-based in our analyses and recommendations. There is an open-endedness to what we have been talking about here”.19 Coddington’s words about conservation seem to echo the overall themes of working with digital art- the art is constantly changing so the institutions must change too.

Moreover, because digital art is ever changing it is difficult to conserve. Frances Lloyd-Baynes, who is associated with the Minneapolis Institute of Art, argues about this issue in the article “When ‘Digital’ meets Collection: How do (traditional) museums manage?”.20 Because digital art has to be displayed through the use of specific equipment, the artwork’s lifespan is only as long as the life span of that type of equipment.21 She states, “And therein lies the problem given the pace of change, it is not a question of if the technology will fail or become obsolete, but when”.22 To combat this issue museums and conservators have to shift their thinking about what they are caring for.23

Most visual art is a tangible object and nothing else. A painting is just a painting. A sculpture is just a sculpture. But digital art exists in a tangible and intangible form, and both forms need to be preserved.24 In order to achieve this the digital art needs to be removed from its initial form and put “[…] into a managed digital preservation environment”.25 Just like an archive for non-digital art, a digital art storage system works best when it is amalgamated.26 After acquisition of a digital art piece, to get the piece into the collected “environment” the museum can utilize a checksum program to get the raw data file of the art.27 The raw data file code is unique to the artwork and can be transferred into similar programs, and therefore will be able to last over time.28 Then, to pair the original artwork to the raw data file the program BagIt can be used.29 Once the digital art has been protected in this way it can be stored. Storage programs used rely on business decisions that need to be made in order to conserve and store these artworks in a sustainable way for both the art and the institution.30 Especially because deciding to store digital artworks will require financial planning, as storage programs vary in size and cannot always be customized after purchase.31

Understanding how digital art exists and its delicacy is how art organizations are able to show audiences digital art from the past. In 2016 the art institution Rhizome debuted the show Net Art Anthology.32 This show was significant because it successfully displayed digital artworks from the 1980s and 1990s.33 The team at Rhizome pulled this feat off because they were one of the first organizations to understand that digital art exists more as an intangible action than a tangible object.34 Zachary Kaplan, the executive director at Rhizome, states, “[…] there is only a performance of code. Our preservation program is built around this idea of preserving performance”.35 Kaplan and his team pulled digital art from superannuated devices like “legacy computers” and “CD-ROMs” and displayed them on a new program that was able to imitate the obsolete equipment.36 Thus, they were able to successfully conserve and show art that would have otherwise been lost to time.

Just like the acquisition process for digital art, the conservation of digital art involves the majority of the departments within the museum. Lloyd-Baynes states, “No one conservator or expert of any kind can address every technical challenge. Specialists from across the digital and museum spectrums must work in partnership to ensure these works survive”.37 The IT department and the Archives department in a museum may seem like a peculiar pairing to solve an artistic dilemma. But conservation of art is steeped in collaboration across fields. The conservation of paintings has seen artists and scientists working together since the late nineteenth century.38 Therefore, it is very appropriate that experts from across disciplines are needed to solve these new issues of how to properly acquire, care for, and conserve digital art.

Bibliography

“AAM Code of Ethics for Museums.” 2017. American Alliance of Museums. December 12, 2017. https://www.aam-us.org/programs/ethics-standards-and-professional-practices/code-of-ethics-for-museums/.

Art, The Museum of Modern. 2018. “Digital Art Storage by Ben Fino-Radin from Workshop 1 (June 11-15, 2018 at MoMA).” Vimeo. August 3, 2018. https://vimeo.com/283104768/0b0e468ed9.

Art, The Museum of Modern. 2018. “The Acquisition Process from Workshop 1 (June 11-15, 2018 at MoMA).” Vimeo. August 3, 2018. https://vimeo.com/283104671/eba9311a32.

Cameron, Fiona., and Sarah. Kenderdine. Theorizing Digital Cultural Heritage : a Critical Discourse. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 2007.

Grau, Oliver, Wendy Coones, and Viola Rühse. Museum and Archive on the Move: Changing Cultural Institutions in the Digital Era. Berlin, [Germany] ;: De Gruyter, 2017.

Lloyd-Baynes, Frances. “Preserving Digital Art: The Innovation Adoption Lifecycle.” 2020. Museum-ID. February 7, 2020. https://museum-id.com/preserving-digital-art-the-innovation-adoption-lifecycle/.

Salarelli, Alberto . “Management of Small Digital Collections with Omeka: The MoRE Experience (A Museum of REfused and Unrealised Art Projects).” Bibliothecae.it 5, no. 2 (2016): 177–200.

Sterrett, Jill.“Codifying Fluidity.” n.d. VoCA Journal Summer 2017. https://journal.voca.network/codifying-fluidity/.

Sutton, Gloria.“A Performance of Code.” n.d. VoCA Journal Summer 2017. Accessed February 22, 2022. https://journal.voca.network/summer-2017/.

“Time-Based Media & Digital Art.” n.d. Www.si.edu. Accessed February 22, 2022. https://www.si.edu/TBMA/#:~:text=The%20Smithsonian%20Time-based%20Media%20%26%20Digital%20Art%20Working.

Wagner, Karin. “Randomness and Recommendations – Exploring the Web Platform of the Artist Ivar Arosenius and Other Digital Collections of Art.” Museum and society 18, no. 2 (2020): 243–257

“When ‘Digital’ Meets Collection: How Do (Traditional) Museums Manage?” 2019. MuseumNext. March 6, 2019. https://www.museumnext.com/article/when-digital-meets-collection-how-do-traditional-museums-manage/.