It is fitting that the quote I intended to open this article with is impossible to attribute to any one person. “Good artists copy, great artists steal” or some similar wording has been associated with artists and “creatives” such as Steve Jobs, Pablo Picasso, T. S. Eliot, Igor Stravinsky, and William Faulkner. I can think of no better quote to set the tone for this attempt to briefly illuminate one convoluted chapter in the exhaustively long and complex history of art theft.

Good artists copy, great artists steal”

Jobs quoting Picasso quoting someone else probably…

Some may think of art theft and conjure ideas of heists involving masterpieces from museums and galleries but in this article, I will be referring a much less cinematic, yet no less important, form of theft: theft related to NFTs. This manifests in two ways: 1) an NFT (as I will define in the coming pages) can be stolen from its owner or creator, and 2) a work of art that exists on the internet can be stolen via the creation and distribution of an NFT. I will focus on the second more complicated example of theft via the creation of NFTs. However, the issue of hackers stealing NFTs is well documented, and no less problematic.

For now, let’s get back to art theft via NFTs. In this case, creative content posted online is being copied, minted as an NFT, and sold all without the artist/creator’s permission. There are a few important and highly nuanced ideas one must understand to fully comprehend this form of art theft.

What are NFTs, really?

First, one must understand what exactly an NFT is. Much to my chagrin, NFT does not stand for “noses feets teefs” as I was promised by many an internet meme, but instead stands for Non-Fungible Tokens.

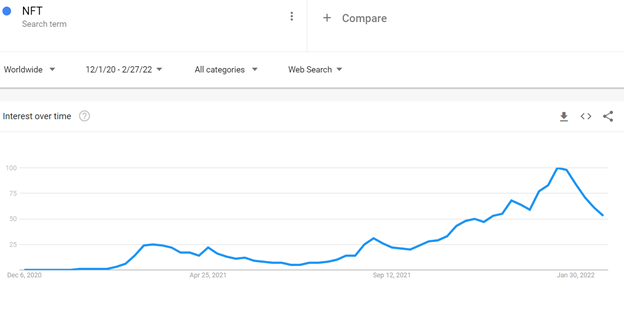

The technology for NFTs has existed since 2014 but started gaining global attention and popularity in early 2021.

Non-Fungible Tokens are a product of blockchain technology, the same technology that creates bitcoins and other cryptocurrencies. Ultimately, NFTs are meta-data that act as a receipt or certificate pointing towards an intangible asset housed on the internet. Blockchain technology enables the creation of a unique and secure receipt or certificate for a digital item. When a digital item is created, as is the case with cryptocurrencies and NFTs, the blockchain “holds” a decentralized record of that item. The key difference between NFTs and cryptocurrency is the “Non-Fungible” part.

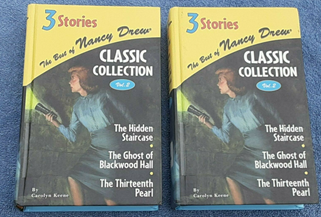

One of the most illustrative analogies is comparing an NFT to a copy of a book like Carolyn Keene’s Nancy Drew Mysteries while comparing one bitcoin to a US $1 bill. Each copy of Keene’s book can appear identical while being completely unique and may have different values on the market. Additionally, the book cannot be broken down into smaller pieces and sold (this is the non-fungible part of NFT coming into play). In contrast, a US $1 bill is also unique thanks to a serial number, but after that, a single US $1 is valued the same as every other $1. Additionally, the worth of that dollar can be broken into change. If this analogy didn’t clear things up for you, you are in good company. Unfortunately, things only get more convoluted from here.

Specifically related to the issue of art theft via NFTs, we need to determine if an NFT includes anything in addition to the meta-data (or “receipt/certificate” for anyone who still feels queasy from even reading the word “meta-data”). The crux of art theft via NFTs really comes down to this point and the answer is not consistent for every NFT minted and sold. Some NFTs exist purely as the meta-data (receipt). To be more explicit this is like owning the receipt from the purchase of a Nancy Drew Mystery novel without owning the book itself. Some NFTs include a digital copy of whatever the receipt refers to (an image file, music file, text file, etc). To refer back to our analogy, this is like owning both a copy of the novel and holding onto the receipt. There may be stipulations to how you can use the file. For example, you could be allowed to personally open the file, but not post it for others to open just as you can read your copy of the novel, but you can’t turn that story into TV show without additional permissions. And finally, some NFTs include the meta-data, a copy of whatever the receipt refers to, and the copyright to that file. This is like owning both a copy of the novel, a receipt, and the publishing rights for all future copies. The distinction between these three categories of NFTs that are minted and sold are often misrepresented (sometimes intentionally) by sellers or misunderstood by buyers and even reporters writing about this latest art phenomenon.

Copyright Law in Regards to NFTs

Now that you are a newly minted NFT expert (one who surely understands and appreciates that joke), let’s move on to The Digital Millennium Copyright Act. Passed in 1998, the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, commonly referred to as DMCA, amended U.S. copyright law with an eye towards protecting copyright from innovations related to the internet and other technologies that could be used to thwart traditional copyright law. In relation to NFTs, the DMCA has specific provisions that govern copyright law today.

- The person who creates or generates a work of art or piece of creative content does not need to actively register that content with the US government to have sole ownership rights. Any unique creative content that is posted or published online is protected from art theft. This includes images or other digital files uploaded to Twitter, Facebook, or any website.

- Online service providers (like YouTube, OpenSea, or any other media hosting platform) are protected by a “safe harbor” rule that states that they cannot be penalized for copyright infringement that takes place on their website if they create “notice-and-takedown” system. These online service providers must designate an agent to receive, review, and act upon grievances brought up in good faith by any individuals claiming their property was used on the site without their permission. This protects online service providers from harm as it is difficult for them to screen the massive amount of data being posted to their sites and it protects artists by giving them what is supposed to be a relatively easy and free pathway to protect their work without the money and time required for formal litigation.

- Ignorance is not a defense against copyright infringement. If you unknowingly purchase a stolen work of art and try to utilize or re-sell that art you can be severely financially penalized.

Here is where the DMCA falls short in practice when artists and other content creators have their work stolen and turned into NFTs.

1) Creating copies of digital work or digital copies of someone’s work is as easy as clicking a button. Additionally, editing software is becoming more powerful and easy to use, so almost anyone can remove watermarks or other tools previously employed by artists protect their works from theft. This means almost anyone including bots can make digital copies of anything posted on the internet without anyone knowing, including the original poster.

2) The internet is vast and if, as established in the DMCA, it is nearly impossible for large online service providers to keep track of what gets posted on their site, it is even more difficult for an individual artist or content creator to monitor every corner of the internet for unauthorized copies of their work. Minor strides have been made using bots to screen for illegal activity, but there are limitations to this solution. Currently, bots are only able to screen files that have been uploaded to specific websites so art thieves can easily avoid the sites screened by such bots.

3) Finally, assuming an artist learns of their artwork being used without their permission, and they report it using the site’s mandated “notice-and-takedown” system, and the site actually takes action promptly (the amount of time a site must process and act on such reports is not spelled out in DMCA) since NFTs and other cryptoart can and is often created and sold completely anonymously, there are few serious ramifications that cryptoart-theives actually face. If an account is shut down, they can easily resurface using another account and continue to mint and sell NFTs using stolen files.

Additionally, if you think back to an NFT in its purest form being only that receipt, not the file itself or the rights to the file, some argue that minting and selling an NFT regardless of the content it is pointing to, cannot be illegal. Afterall, if I write “You now own Nancy Drew and the Hidden Staircase” on a piece of paper, and sell that paper – not a copy of the book, nor a contract that outlines and includes the rights to the story – just that paper, I have not broken any laws. Some argue that is all any NFT is and if the buyer doesn’t understand that and then goes to make a new Nancy Drew movie, only the buyer of the NFT could be held responsible, the seller would not be liable or even necessarily traceable. Afterall, the DMCA makes it clear that ignorance is not a defense against copyright infringement. The complexity and lack of education around NFTs leads buyers to be at risk of thinking they are purchasing a valuable work of art and ending up with little more than a digital serial number.

Conclusion

Let’s think back to our dear friends Picasso and Stravinsky and remember this proverbial tale is old as time. Art is the twin born only seconds before art theft and digital art theft has always been an issue that artists face when trying to publicize or sell their work online. However, the sensationalism of NFTs as the new “it” thing in the world of art, tech, and finance paired with the high price tags associated with many NFTs and the ability for people to steal a vast amount of art with minimal effort thanks to bots has only intensified the issue. Many artists have been driven away from digital platforms as they no longer feel like safe or profitable tools for advertising or selling their art. As artists flee from these platforms as marketplaces, they are also being forced to abandon online artistic communities where they could once find friendships, collaborators, peer support, and inspiration.

This fact is even more distressing when you consider that many digital platforms and NFTs were created with the goal of supporting and protecting artists and content creators. These tools were meant to democratize and art and art markets by protecting ownership rights while making access to all manner of art easier for anyone with internet access. Instead, they have put a stranglehold on creative content generation, manufacture artificial scarcity, and financially reward investors and prospectors over artists and art lovers.

References

Berg, Chris. “Non-Fungible Tokens and the New Patronage Economy,” March 22, 2021. https://www.coindesk.com/business/2021/03/22/non-fungible-tokens-and-the-new-patronage-economy/.

“Calling All Creator Platforms to Fight Art Theft by Team on DeviantArt.” Accessed February 27, 2022. https://www.deviantart.com/team/journal/Calling-All-Creator-Platforms-to-Fight-Art-Theft-901238948.

Dash, Anil. “NFTs Weren’t Supposed to End Like This.” The Atlantic, April 2, 2021. https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2021/04/nfts-werent-supposed-end-like/618488/.

Dexerto. “Top 10 Most Expensive NFTs Ever Sold,” February 17, 2022. https://www.dexerto.com/tech/top-10-most-expensive-nfts-ever-sold-1670505/.

Gerard, David. “NFTs: Crypto Grifters Try to Scam Artists, Again.” Attack of the 50 Foot Blockchain (blog), March 11, 2021. https://davidgerard.co.uk/blockchain/2021/03/11/nfts-crypto-grifters-try-to-scam-artists-again/.

Gizmodo Australia. “NFT Theft Is Still Plaguing DeviantArt, Despite Fraud Detection Tool,” December 20, 2021. https://www.gizmodo.com.au/2021/12/deviantart-nft-theft/.

Hagan, Karsh. “Using NFTs to Protect Creative Works | Karsh Hagan.” Karsh Hagan Advertising, May 24, 2021. https://karshhagan.com/news/2021/05/24/using-nfts-to-protect-creative-works.

Kinsella, Eileen. “‘All My Apes Gone’: An Art Dealer’s Despondent Tweet About the Theft of His NFTs Went Viral… and Has Now Become an NFT.” Artnet News, January 5, 2022. https://news.artnet.com/market/kramer-nft-theft-turned-nft-2056489.

Liscia, Valentina Di. “Artists Say Plagiarized NFTs Are Plaguing Their Community.” Hyperallergic, December 28, 2021. http://hyperallergic.com/702309/artists-say-plagiarized-nfts-are-plaguing-their-community/.

Mattei, Shanti Escalante-De. “Thieves Steal Gallery Owner’s Multimillion-Dollar NFT Collection: ‘All My Apes Gone.’” ARTnews.Com (blog), January 4, 2022. https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/todd-kramer-nft-theft-1234614874/.

Munster, Ben. “People Are Stealing Art and Turning It Into NFTs.” Vice (blog), March 15, 2021. https://www.vice.com/en/article/n7vxe7/people-are-stealing-art-and-turning-it-into-nfts.

Nast, Condé. “An Artist Died. Then Thieves Made NFTs of Her Work.” Wired UK. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://www.wired.co.uk/article/nft-fraud-qinni-art.

NBC News. “Artists Say NFTs Are Helping Thieves Steal Their Work at a Jaw-Dropping Rate.” Accessed February 23, 2022. https://www.nbcnews.com/tech/security/nft-art-sales-are-booming-just-artists-permission-rcna10798.

NFT thefts. “‘We Are Not Seeking Permission’ Https://T.Co/Y8SNnWPpdw.” Tweet. @NFTtheft (blog), February 21, 2022. https://twitter.com/NFTtheft/status/1495807542274019332.

“Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs) and Copyright.” Accessed February 26, 2022. https://www.wipo.int/wipo_magazine/en/2021/04/article_0007.html. Engadget.

OpenSea. “What Can I Do If My Art, Image, or Other IP Is Being Sold without My Permission?” Accessed February 23, 2022. https://support.opensea.io/hc/en-us/articles/4412092785043-What-can-I-do-if-my-art-image-or-other-IP-is-being-sold-without-my-permission-.

“OpenSea Faces $1 Million Lawsuit over Stolen Bored Ape NFTs.” Accessed February 23, 2022. https://www.engadget.com/open-sea-facing-1-million-lawsuit-over-stolen-bored-app-nft-133044623.html.

“The Digital Millennium Copyright Act | U.S. Copyright Office.” Accessed February 26, 2022. https://www.copyright.gov/dmca/.

The Gamer. “Artists Share Their Frustration Over Stolen Artwork Becoming NFTs,” January 19, 2022. https://www.thegamer.com/artists-share-their-frustration-over-stolen-artwork-becoming-nfts/.