Virtual Reality has been an ongoing trend in the art world. While more and more museums adapt to VR technology, some among them have gone one step further — they do not exist as a physical entity at all. This study reviewed three digital museums, each taking a different approach, and oriented with different techniques, trying to bring a new way of engaging with arts to a broad audience.

Finally, the need for a new appropriate museum and archive infrastructure is shown to preserve the art of our time.

Digital Art Through the Looking Glass, Grau, Hoth and Wandl-Vogt

Alongside the constant evolving of technology, digital art has modeled itself into its best possible version. While the talents use digital tools to create more and more diverse and cutting-edge art pieces, it gradually becomes a significant form of contemporary art standing on its foot. Feeling a strong need to create a space dedicated to presenting digital art in its own context, the Museum of Contemporary Digital Art came to life.

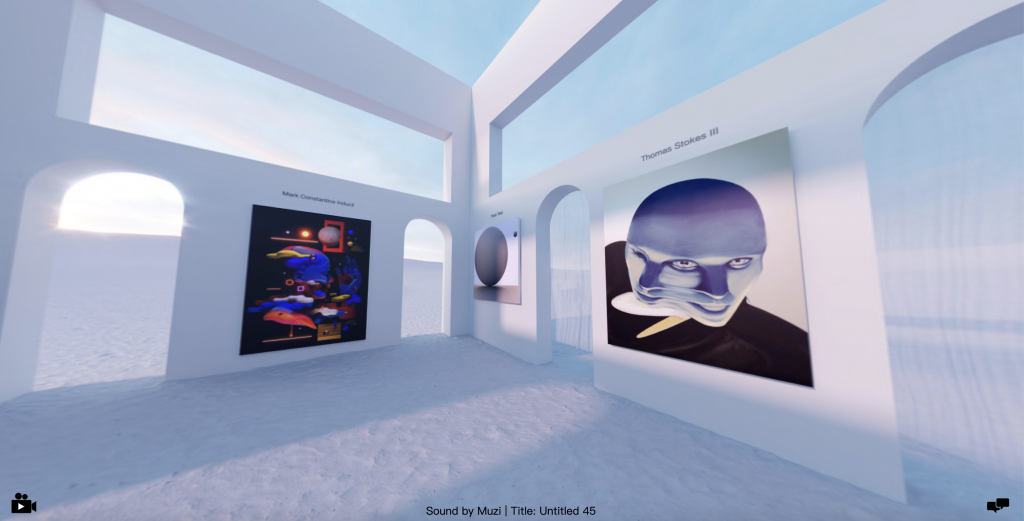

The Museum of Contemporary Digital Art (MoCDA) is a digital-based museum that “exhibits digital artworks to document, collect and advance the position of digital art.” Their primary focus is education and the endorsement of contemporary digital art. Its exhibitions could generally be categorized into three different types: virtual exhibitions based on the museum website, virtual exhibitions generated by other virtual world platforms, and new media arts exhibited directly on the website. System Shock – 777 Exhibition is a first type, in which users enter the virtual space by clicking on a link to the web page. It is viewed from the first perspective and adapts the design language of traditional exhibitions. One can zoom in and out on any part of the exhibition space. And in some cases, users can follow the arrow on the ground to enter several rooms. The exhibition is accompanied by background music. By clicking on the chat sign on the right bottom of the page, users will see how many people are in the exhibition and chat with each other.

The exhibition, MEMENTO MINTI – if you stop contributing, you will be forgotten, was presented via Decentraland, a 3D virtual world. It is an example of virtual exhibitions generated through VR platforms powered by blockchains, in which users can purchase virtual plots of land, craft, and monetize the contents within the virtual world. This shared metaverse allowed MoCDA’s exhibition to be much more sophisticated. Before entering the virtual exhibition, users get to create their own avatars (though with quite limited options for free). From a first glance, the environment shares the simple blocky graphics that would remind people of Minecraft. The exhibition space was held in the MoCDA virtual building and consists of three stories.

Like the web-based virtual gallery, the interior of MoCDA Building follows the basic design language of the real-space exhibition. Similar applications such as background music and the chat room can also be found in the virtual museum. Except this time, users have a lot much more freedom in controlling the movement of avatars, and are able to pull out more complicated action commands, such as jump or interact with the artwork. In general, the experience with MoCDA’s virtual museum in Decentraland is more like navigating in a game setting.

The third type of exhibition is based on the web page, so visitors do not have to open another tab to enter the exhibition. The exhibition Digital Bodies – concerning bodily structures showcases blockchain-based tokens. Although it appears like a regular GIF on the website, it is in fact a unique 3D model registered on the blockchain. Thus, MoCDA is both creating traditional exhibitions in a virtual space, and presenting arts made with the latest technology.

In light of MoCDA’s commitment to education, the institution holds live talks with digital artists, curators, and art experts. The talks are live-streaming, and those recordings of talks can be revisited on the museum website.

A museum without gravity, plumbing or code regulations.

Johan van Lierop

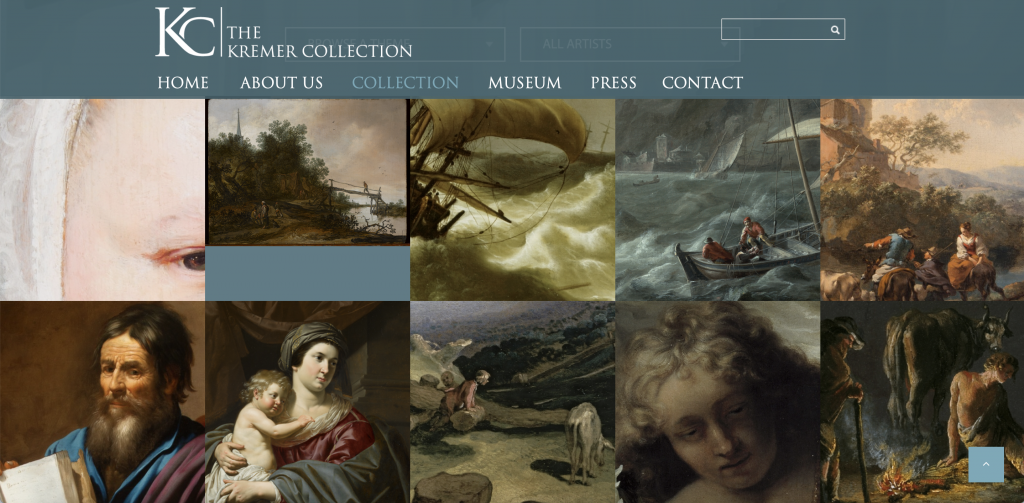

Unlike MoCDA, which showcases works meant to be consumed through VR, the collection of the Kremer Museum “forced” the old masterpieces into a digital recreation. The museum is an extreme case of VR taking over the physical entity. It displays over 70 Seventeenth-Century Dutch and French paintings of George Kremer’s collection in exclusively virtual space.

Each painting has been photographed between 2,500 and 3,500 times with the “Photogrammetry” technique, resulting in an ultra-high-resolution model for each work. The collection includes great masters such as Gerrit Dou and Rembrandt and less famous but exciting and worthy artists such as Abraham Janssens and Theodoor Rombouts. The idea is to make it truly accessible to all people to see the masterworks in a museum setting. Johan Van Lierop, an architect and the designer of the museum, believes VR is ” to the 21st century what Dutch Realism was for the Golden Age, allowing the observer to escape into an alternative reality or mindset.”

The paintings of the Kremer Museum can be viewed under the “Collection” section. The full-sized painting and a detailed introduction to the work will pop up by clicking on each piece. Visitors can then zoom in on any part of the painting to view it close-up. It seems like they worked really hard to recreate the unique colors of individual artworks and feel their textures, such as small cracks of pigments resulting in a long period.

The Kremer Museum can be downloaded from various app stores, including Apple, Google Play, Steam, Meta Quest, as well as Vive Port. A VR experience is also made possible through the headsets.

A hub for debate and discussion around innovation through the digital.

Lee Cavaliere

Launching in 2020, Virtual Museum of Arts (VMOA) is the world’s first entirely virtual museum. It collaborated with some of the most prestigious museums worldwide, such as the Museum of Modern Art, Chicago Institutes, and the Musée d’Orsay. It recreated the 3D reproduction of works from over 40 artists varying in time, styles, and places, such as Henri Matisse, Francisco Goya, Frida Kahlo, and Bansky.

To visit VOMA, users can simply tap on the “Enter” button from the homepage and then launch on the entrance. By clicking on the white circles, users will be able to move around in the virtual space and drag the mouse to have a 720-degree view of the space. There is the built-in sound of running water, corresponding to the waterfront surroundings. At the same time, plants are in motion with the wind to create a generic imitation of nature. Architect Emily Mann even managed to change the scenery according to different times of the day and weather.

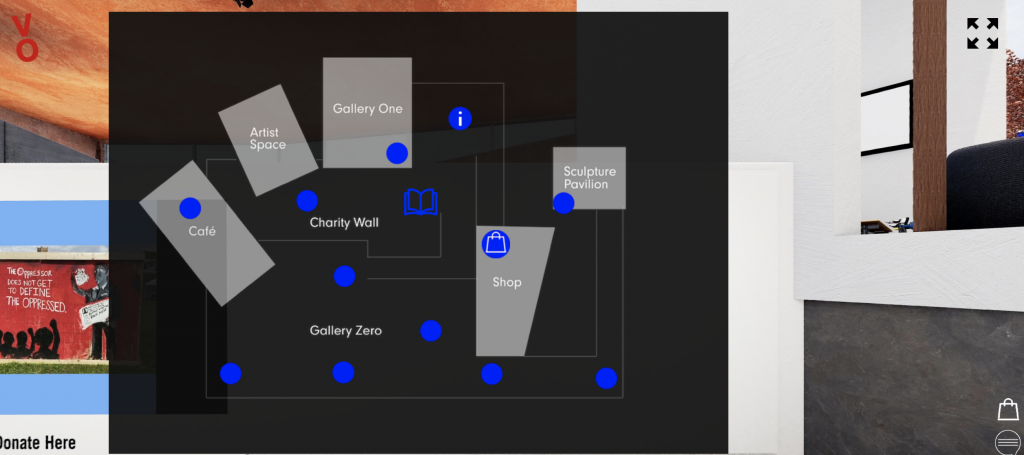

When entering the gallery space, users can click on each piece for more information, as well as to zoom in and out. Some of the video installations will be viewed via Youtube. Map, catalogs, and the chat function are available on the bottom of the page. Users can either use the map or follow the staircases to move to other sections. Compared to the virtual museum of MoCDA, which has users to take the trampoline-like installation to jump to different floors, transferring through the staircase seems a more realistic experience. However, the limitation of only being able to move to the designated spot of the circle may undermine such realistic efforts.

There is also a cafe, which serves as a chat space for users to message other users sitting on the same table. The reading room is an online archive with materials to featured artists, and the shop sold merchandise such as the reproduction of paintings, T-shirts, and notebooks. All of those applications are closer to the usual web-browsing experience instead of a more interactive touch.

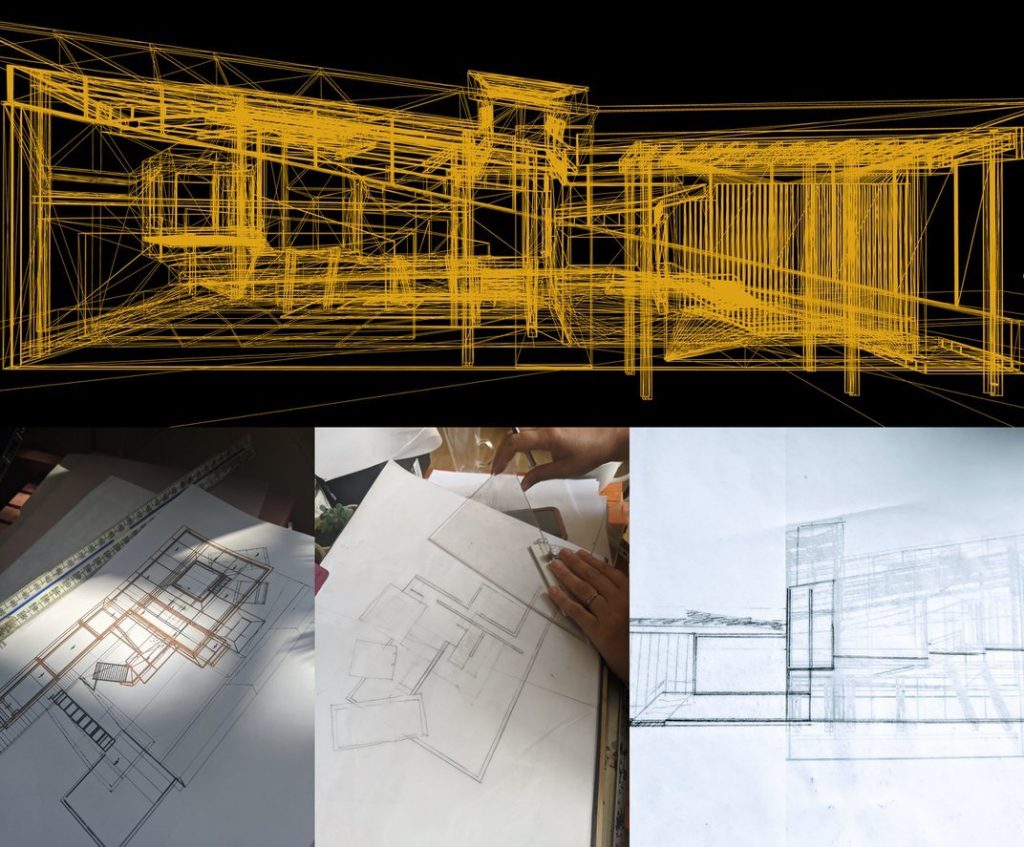

Compared to the MoCDA, which wants to create a place for digital art to be displayed in its original context, and Kremer, who challenge the physical means of old masterpieces, VOMA is less radical in its agenda. Instead, it focuses on developing a fully immersive experience with the latest technology. Stuart Semple, the creator of the VOMA, brought together a team of programmers, video game designers, and architects to build the museum from scratch. They attempt to restore all the essential components one would expect from a physical museum, including a uniquely designed architecture, external surroundings, gallery space, cafeteria, and bookstore.

What does VR mean for museums?

We see VR museums grapple with the means of digital and push the boundaries. From MoCDA’s creating a space for digital art to Kremer’s converting physical paintings to an exclusive virtual view to VMOA’s fully immersive museum. They claim the legitimacy of digital art forms in their own language as something more than just a by-product of the art world. In doing so, they challenge audiences on to what extent we would refer to creation as art and who gets the access, and what to expect as an audience of the museum.

One thing particularly interesting is that, among the three, Kremer is the only one who decided not to attach their paintings to a virtual wall. By depriving the works of the physical substance, but replicate the exact features of the original painting in a way that you will expect to see with human eyes (or even clearer and allows more freedom to observe in detail. Are there more we are asking from the museum? Is there something fundamentally essential and satisfying about the experience of physically walking through piece by piece? The answer can vary for different people, but the existence of virtual museums opens up the dialogue for it.

Resources

“About: Museum of Contemporary Digital Art.” Accessed February 20, 2022. https://www.mocda.org/about.

“The History of the Kremer Collection.” The Kremer Collection. Accessed February 21, 2022. https://www.thekremercollection.com/history-of-the-collection.

“Decentraland. “Accessed February 20, 2022. https://play.decentraland.org/?island=I9xzhu&position

=-21%2C116&realm=dg&server=loki-amber.

“Home – The Kremer Collection.” The Kremer Collection. Accessed February 21, 2022. https://www.thekremercollection.com.

“Intelligence 0296, VOV, Maurice Benayoun: Museum of Contemporary Digital Art.” MoCDA. Accessed

February 20, 2022. https://www.mocda.org/maurice-benayoun-intelligence.

“The Kremer Museum.” The Kremer Collection. Accessed February 21, 2022. https://www.thekremercollection.com/the-kremer-museum/.

“Live Talks and Podcast: Museum of Contemporary Digital Art.” MoCDA. Accessed February 20, 2022. https://www.mocda.org/live-talks.

Magazine, Smithsonian. “The World’s First Entirely Virtual Art Museum Is Open for Visitors.” Smithsonian Institution, September 17, 2020. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/travel/worlds-first-entirely-virtual-art-museum-is-open-for-visitors-180975759/.

“System shock – 777 exhibition.” Accessed February 20, 2022. https://www.mocda.org/system-shock-777-exhibition.

“Virtual Online Museum of Art (VOMA) Officially Opens Online.” Blooloop, January 18, 2021. https://blooloop.com/museum/news/virtual-online-museum-art-voma-open/.

“Virtual Reality Is a Big Trend in Museums, but What Are the Best Examples of Museums Using VR?” MuseumNext, January 20, 2022. https://www.museumnext.com/article/how-museums-are-using-virtual-reality/.

“VOMA – Virtual Online Museum of Art: A Virtual Online Museum of Art.” VOMA virtual online museum of art. Accessed February 24, 2022. https://voma.space/.

“World’s First Virtual Museum VOMA to Launch next Month – with Your Help.” FAD Magazine, May 7, 2020. Accessed February 24, 2022.https://fadmagazine.com/2020/05/07/worlds-first-virtual-