In contemporary captures I would not consider the medium objective overall, however I do think, depending on how it is used, it is one of the most objective mediums we have available. Regardless of the “accuracy” (I would define this as the precision with which a capture recreates what exists in the moment of capture), there is still an element of the objective that cannot be separated from the creating on the capture itself. The choices made in the capturing, and in the interpretations of the data are what make the mediums of capture and the typologies they present “a malleable material.” The accuracy of the technology we have to use in capture has changed and developed over the history of photography. It has provided us with information that exposes us to understandings of our world that can be measured, standardized and observed in ways that we cannot measure or see without these tools. The x-ray and astronomical capturing provides us with insights in the scientific field that are undeniably important, through processes that we understand as being scientifically reliable. However I do not think that scientifically reliable always equates with objectivity, nor predictability.

Category: Reading02

Reading 02: Photography and Observation

I’m interested in the transition from observing as an art form, to observing as a passive act of science. It’s inspiring to know that something as culturally concrete as physical perception can be flipped on its head by the invention of tools. The medium a photograph is captured in can have obvious effects, like if the data being collected even describes the state being recorded. This seems to be the overarching goal of these scientists and artists experimenting with capture medium; to convert world data to visual representation by whatever means necessary. The objective value we prescribe to sight is what gives photography so much power. We can believe that what we see is what is real, but we only see the abstracted information our eyes and brains (organic cameras) are able to immediately present to us in forming our perception of physical space and the events that take place within it. It makes me wonder if it was necessary to rationalize the possibility of photographs and illusions to rationalize our own sense of sight as a similarly organized phenomenon.

Photography is now so widely available and consumed, that the realization of sight as a medium doesn’t even expose its fragility in the same way. Being born into a culture guided by manufactured icons, we can’t help but associate them with natural reality. If you had to struggle to see things, or if you were made immediately aware of the great lengths and processes needed to produce such images, you would understand the nuanced reasons why photographs don’t express reality, and are only estimations with limited focus. Because photography aims to transcend process, and just present a neatly bundled product, these considerations aren’t necessary to make in its everyday application.

Photography and Observation Response

The methods employed to capture a typology, when applied to a newly defined typology, can define how that group is perceived. For example, many of the telescopes used to capture images of planets within our solar system capture images in wavelengths outside of the visible spectrum and translate that into visible light. Because of this, we often imagine planets in colors that don’t match what they’d look like if we were actually looking at them with our eyes.

Capture techniques can always be used demonstrate a particular thing or to make a certain point, and because of this, anything captured can be subjective. In fact I would argue that it is incredibly challenging to produce an objective means of capturing something. Because the capture of something is shaded by our interests to capture a certain aspect of that object/event, it is extremely rare that a captured image represents the totality of the object, making it very unlikely for that image to be objective.

If well-standardized, a capture under the right conditions can be incredibly predictable. One could potentially capture the same aspect of an entire typology, which could then demonstrate whatever observation the individual is trying to show. Because of this predictability, capture is an essential tool in scientific research. While it might not be entirely objective, it is often necessary for a subjective representation to exist to highlight a deeper, objective truth.

Photography and Observation Response

I find in the mentioned “impulse” to measure photographs an interesting dilemma. At one level I view photographs as an entirely subjective medium, much in the same way that science is fundamentally biased and yet still offers an understanding of our world, but there is level of objective truth to them, or at least there once was. Scale and form, fundamental principles of photography and film, form what I believe to be the basis of this measurement, but in many ways the impulse to measure these fills inapt to me largely because their own nature is a subjectively framed through the eye of the photographer. Taking this, and applying it to the Typology, conceptually I feel the typology is a facet of organising these subjective approaches. Much in the way that these typologies act out as machines that repeat the same task, the typology is a repeated subjective framing. There is little to no objectivity in the typology, with the capturer using the capturing as a kind of sausage machine to produce the typology.

My own notion of a scientifically reliable capture was somewhat distorted after visiting the SEM, with the physics involved in it becoming all the more pressing and present. The reading highlighted this quality a little, but I find in the contemporary setting of 3d scanning and the like, the notion of being confined to the 2d image with regards to 3d space still felt exceptionally stifling. However, what I did find intriguing was the idea of being able to capture movement in the 2d image, since the rasterising allowed for the moving sample to be captured. To me, this spells the interesting dilemma between objective and subjective capture, wherein the purposeful use of objective physics translates into a subjective desire to push the notion of an image to its periphery.

Reading #2

This reading covered a myriad of capture technologies and how the variability and idiosyncrasies of the technique influenced the result, concluding that photography is far from ‘objective.’ In contemporary captures, the medium is far more predictable than it was over a century ago. We no longer have to deal with film irregularities and such, and cameras with simple UI are available to anyone with a cellphone, rather than experts only. One quote I particularly enjoyed described how photography was seen as a rational, enlightened pursuit:

“Observing was considered an art, reserved for those exceptional, diligent and above all sharp-eyed devotees of the natural world and the heavens.”

As pretentious and idealistic as these concepts seem today, I understand the defensive attitudes of individual photographers and the discipline as a whole. Considering the scientific method was not as widely accepted as the foundation of truth (not that it necessarily is now,) any lapse in the objectivity and reliability of measurements, like wobbly photos of the moon, could undermine the entire endeavor. It’s interesting to imagine what photography would look like today if it had originated as a tool of religious and faith-based belief systems rather than scientific ones.

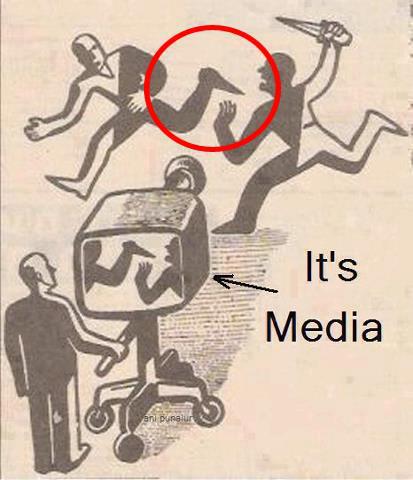

However, photography is no more objective than it ever was. If it weren’t painfully obvious that images can be used to manipulate ‘truth,’ we wouldn’t have this highly complex political cartoon (only intellectuals can understand, sorry.)

There genuinely are different kinds of truth. One of my favorite ideas from the reading was botanical illustrations that showed a flower in all stages of growth, collapsing time and idealizing a living thing:

“These images were true and scientific representations of nature, just like photographs, but they relied on an entirely different understanding of the truth claim.”

Finally, a quote on what makes a photograph interesting. Maybe it’s the failures of a photograph as a tool that make it a good way to make art.

“Measuring photographs that also offer accidental pictorial details are, on the other hand, more likely to survive in archives.”

Policarpo Baquera’s ‘Photography and Observation’

Historically, art practice has been consistently mastering the tools and defying the mediums to achieve a new objective and subjective perception of the physical world. Capturing techniques, from writing, painting, sculpting, or photographing, force the author to work along with the limitations of the medium, but art insistently refuses to admit these rules.

John Gribbin, in his text ‘Photography and Observation,’ exposes how in post-photographic times, science decided to rely on the supposed objectivity of photography to observe and measure natural phenomena and living creatures. Even more, different techniques such as microscopy, astronomical observation, or spectrometry, promised ‘to see plainly where the human eye would find nothing but darkness.’ This leads science to trust blindly in cameras to their research work. Nevertheless, far for being utterly reliable, photography has been evolving much from the nineteenth century: dry plates, daguerrotypes, x-ray imaging, or digital sensors. However, while photography matches better our vision every day, disciplines such as medicine still depend on diagrams and drawings to explain time-depending processes.

So while I think that contemporary capture techniques can be highly reliable and precise for measuring purposes in engineering, architecture, and sciences, before choosing them as documenting tools, we should study their suitability over other ‘less objective’ techniques.

In my personal, professional experience as an architect, any digital capturing (cameras, phones) or displaying devices (screens), will not ever substitute a physical representation of a devised design. All of us are equipped with high-quality cameras in our phones, but even like that, texture and color are still not captured with the same accuracy and also error of our eyes. Digital image processing software is designed mainly to please our senses, not always to describe the reality naturally. Consequently, I could not affirm that the medium is objective unless we talked about high-fidelity instruments, where their cost will lead to discussions as to whether objectivity is only affordable to the scientific or professional community.

Reading02 – Photography and Observation

The medium of capture can influence typology in terms of sample size. The capture system developed depends on the capture’s scope and limitations. The goal of typology is seemingly to collect all or find as many possibilities of a certain type and different modes of capture can restrict findings. For instance, a photographer taking photos inputs a personal perspective and arrangement while leaving an automated camera can limit data by having only one angle of view. Either way there is preference present in the systems set up, so it is rare that any data collection is completely impartial.

It’s also difficult to argue that contemporary captures are objective or scientifically reliable because it depends on the case in which the capture is made. However I do think captures can bring out patterns or enforce and detect predictabilities. No capture can be 100 percent reliable, but patterns captured in a larger sample size give a higher chance of reliability.

Photography and Observation

In the context of this class, a capture is synonymous with a piece of data. It seems, then, that any collection of data could be considered a typology. For this reason I think it is inaccurate to consider “capture” a single medium–perhaps it generally categorizes the devices we use to make typologies, but I think the type of data itself should be considered the medium.

The article’s definition of objective seems to be “a recognizably real representation” of the world. By this definition, I don’t think many contemporary capture technologies create typologies that are necessarily recognizable nor representational> Especially in art, sometimes artists. but they are definitely real. This makes me realize it’s interesting to think about what is “objective” and what is real. Is reality the realness of objects in physical space? or of our eyes perceiving the signifier and our brains interpreting that as a signified? or of the schema we’ve learned to remember at the cognition of the object? Does an object have to be a physical thing or can it be a thought? There’s layers and layers of reality.

The question of reliability is a bit more complicated. I think it comes down to the purpose of the typology. If the data in the typology was created purely for measurement, then obviously it is reliable. This data exists only to describe, and they are generally predictable because they describe reality. But when capturing became an art and emotion and interpretation got thrown into the mix, art typologies could not simply exist; they commented, caused, and affected. A typology created for art has opinions of its own, and it shows the world through a filtered lens.

Reading response #2

In contemporary captures I don’t consider anything objective. After reading about the history and development of different photographic processes it seems like it never was objective. What seems to have been objectively present was the quest for a capture situation that would be objective. A desire, in the western tradition of the enlightenment and its relation to the scientific method, to make something verifiable by reproducibility and replication. So, while there may be tools that can now generally reproduce roughly the same image in a repeatable way, it is not that the process is objective, but more that the journey towards seeking something objective has resulted in something that is close to agreeable in a more generalized way. This idea about process in relation to identifying an objective image is different than a predictive one. While objectivity I think is inevitably wrapped up in the human-perception centric sense of the creators if the image technology, I think there are at this point chemical process for capturing light (or other capture techniques) that can be predictable, or likely to be repeatable. And is predictability what is tied to the veritas of objectivity? That is the question I would posit at the end of this reading.

Photography and Observation

Capture’s influence on typology and objectivity is a debated topic. Some lean to the side of “the camera cannot lie,” while others say that the camera “does not do justice” to its subject. To capture, one generally uses tools. The more complex these tools become, the more chance bias can appear inherently in the data secured. One can look at Kodak and Shirley Cards as an example of bias in even how a photograph represents its own capture. Furthermore, in the context of art or design, a typology displayed is the result of some curatorial decision. Even to show every photo, recording, or point captured is a value judgement about the data, which is subject to the bias of the curator. To say one captured some datum is to say that datum was processed through a series of filters logical and mechanical, which inherently changes the perception of the subject.

That’s not to say capture is not useful, or reliable. Many tools are predictable, and allow for scientific research. MRIs, X-Rays, thermostats, barometers and other capture tools reliably feed out similar enough data each iteration that we feel comfortable letting it inform our decisions.

In the context of typologies, there is a certain ego to curating a selection of data and proclaim one has discovered or identified some special category. Who is anyone to proclaim that someone is a hero, or that this is a house, while this is a home?