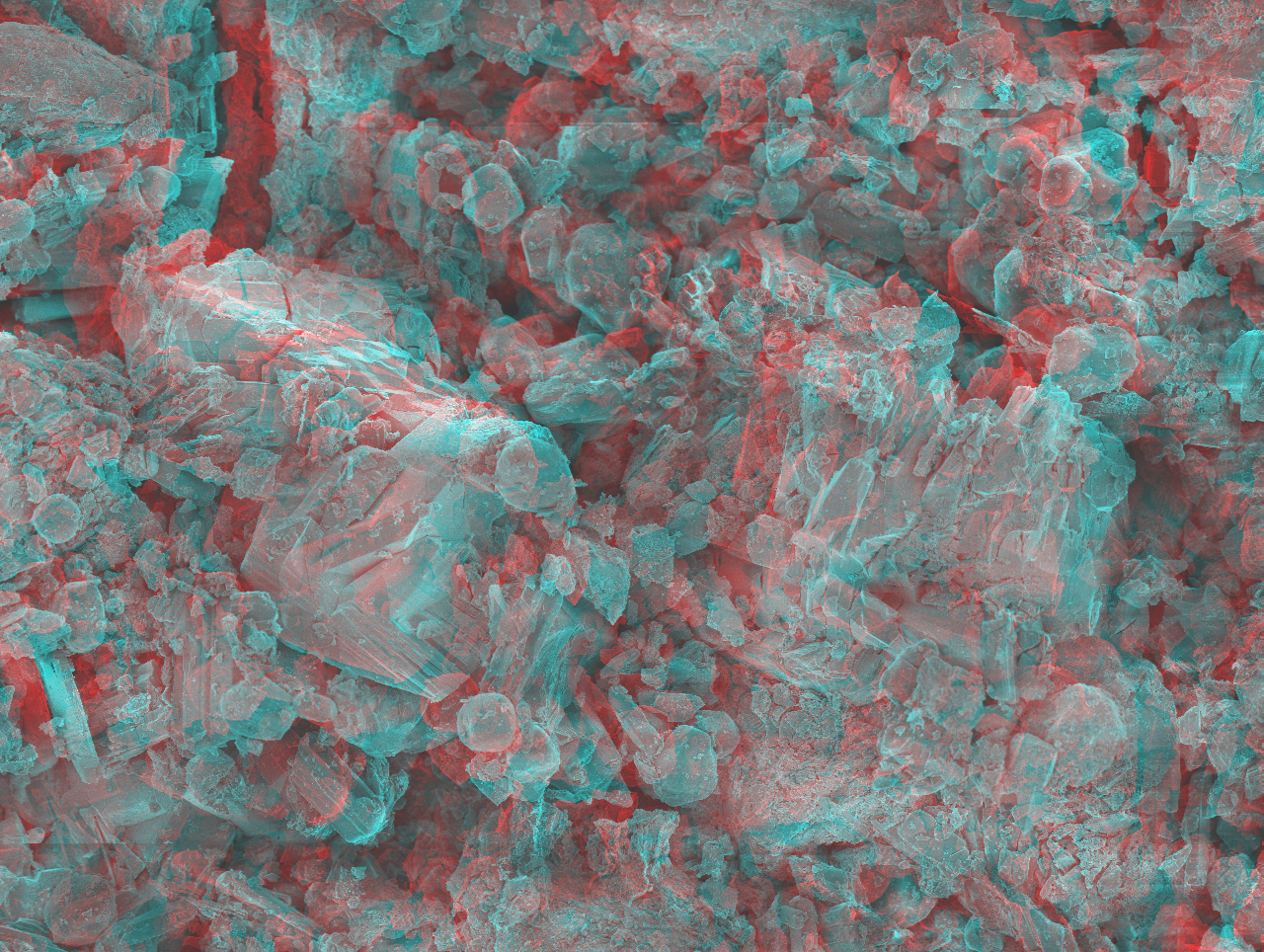

I wasn’t totally sure about other examples of postphotography, so I looked at some other classmates responses, a lot of which were astronomy-related. This made me realize a cool example — how astrophotographers colorize their photos of space, especially of galaxies and phenomena from light-years away. We obviously cannot see these objects because they are too far away, but if they were close enough, our eyes still aren’t complex enough to be able to understand space in a lot of color. The technique that astrophotographers use to add color to their images is similar to what we did with Photoshop to create the anaglyphic versions of our SEM images. They take one set of three different photos of space, each one filtering only red, green, or blue light, and often a second set as well, which filters for light coming from places with hydrogen, oxygen, and sulfur (I’m not exactly sure how that part works). Then they are combined to create a single RGB image. Read here.

As for Zylinska’s paper — I appreciate how she has invented a subcategory for this kind of media, as I don’t think photogrammetry, LIDAR imaging, etc. should be grouped with traditional photography. This may just be my biased opinion as a relatively experienced photo-taker (“photographer” these days seems to be a loaded label), but as I said in a previous response, but I believe the relationship between the human and non-human in postphotography isn’t as close as Zylinska claims, and this paper somewhat scares me as a result. I find myself defensive on analog photography’s behalf. I am absolutely supportive of exciting technology, and a lot of my own art uses it, but my wish is that all these data-driven capture techniques get their own name without “photography”.