In the 50s and 60s, psychological research was lead by behaviorists and psychoanalysts that supported the idea that we, as humans, became attached to our mothers because they provide us with food. Harry Harlow’s studies with monkeys -now unethical- revealed that our healthy development compromised more than nourishment and personal livelihood. Love was part of this equation. As we grow, we extend the boundaries of our affection to other individuals – sometimes even to non-human objects.

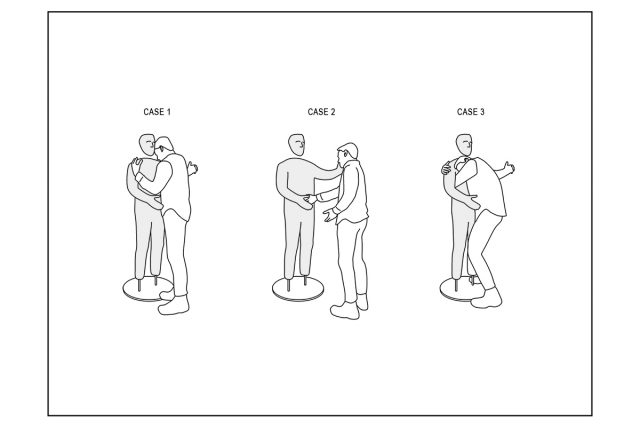

In highly-intertwined technological times, sometimes, this affection is shown as data messages, photos, phone calls, or 1-day-delivery Amazon packages. In this scenario, our caress has to travel through a devious matrix of data filters until it reaches the final recipient. But still today, we have not lost many other physical shows of affection: the hug. Almost universal to all our cultures, hugging is one of the most sophisticated ways of communication. Polite, intimate, or comforting; passionate, light, or quick; one-sided, from the back, or while dancing. Hugs have been widely explored compositionally from the perspective of an external viewer, or from the personal description of the subjects that intervene in its performance.

Statement of purpose

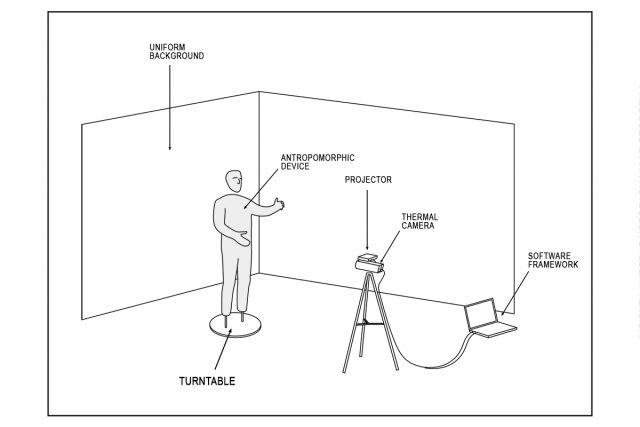

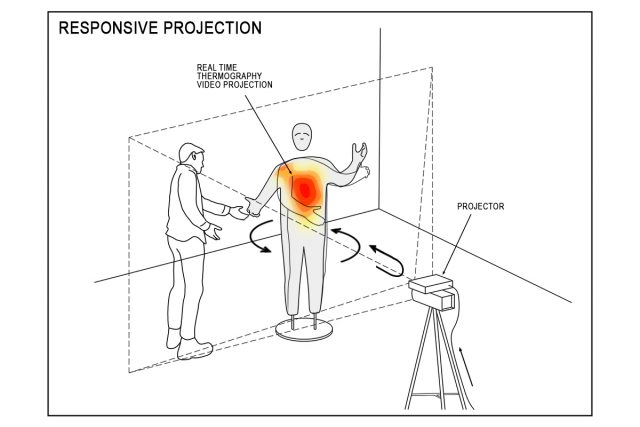

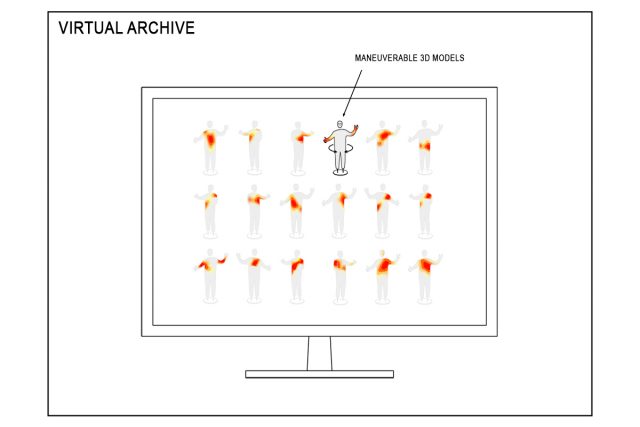

In contrast, I want to study them with a phenomenological attitude and, as James J. Gibson states, from ‘where the action is,’ the outer layer of the physical matter, its surface. For that, I will measure the same surface that intervenes in this affection interchange. Not only is a hug a pressure interaction, but it is also a heat transfer that leaves a hot remnant on the surface once hugged. Using a thermal camera, I will be able to see the radiant heat from the contact surface that shaped the hug. This thermogram will be after projected in real-time onto the ‘anthropomorphic huggable device’ for the study volunteer to view. Parallelly, the temperature information will also be collected to reconstruct 3d models of the hugs using photogrammetry in a virtual archive.

Logistics

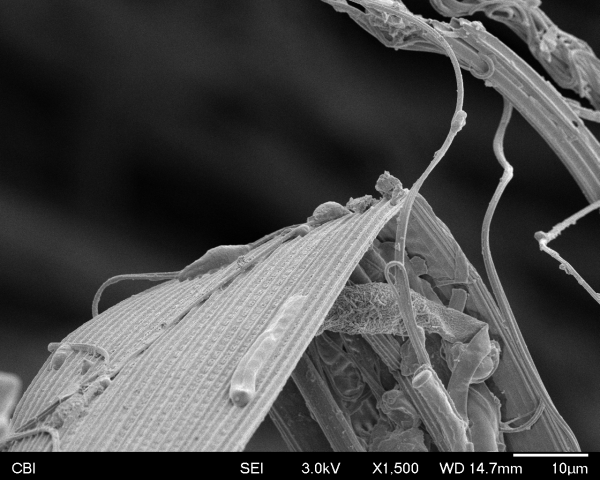

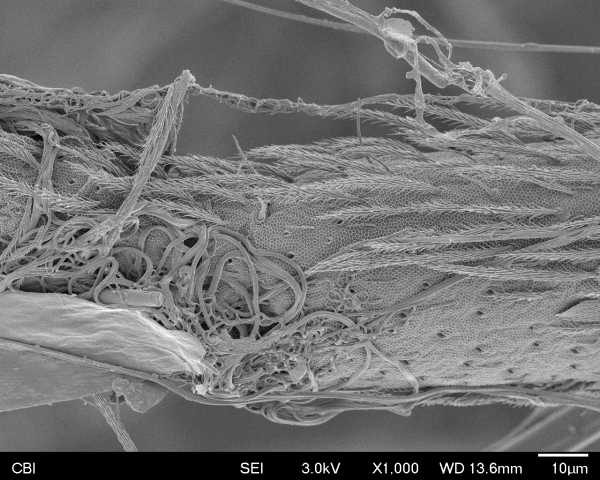

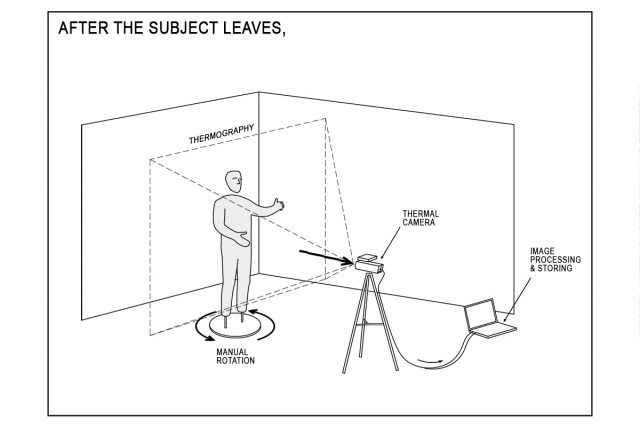

The installation will consist of an ‘anthropomorphic huggable device’ placed on top of a manual turntable that will be dressed with a high thermal effusivity material, like polyester. A higher thermal effusivity allows materials to be thermally activated in a more rapid manner – and therefore, a more thermal load can be stored during a dynamic thermal process. This way, the heat footprint will be more intense and will be perceived in a higher contrast with the rest of the surface, allowing a better thermal capture.

Opposed to the huggable device, a thermal camera (Axis Q19-E), and a small projector will capture the heat and project back the image onto the real surface. Both will be connected to a software framework that will apply a bandpass luminance filter to the image to isolate the hugged area from the rest of the image.

Simultaneously, I will use an external DSLR camera calibrated with the thermal camera to record a set of images used to rebuild the hug in 3D through photogrammetry. Finally, the thermal images will substitute the 3d models’ real textures. A 3d interface will collect all models as a virtual archive of the typology.

References

This project is inspired in the work of artists like Linda Alterwitz that explored thermal portrait photography in ‘Signatures of Heat’ (2012-2017). It also aims to be contextually placed around the ‘Body Art’ artwork explored by cuban-american artist Ana Mendieta in ‘Body Tracks’ (1982).