As a NON-photographer, it was really useful for me to get this history lesson from “Photography and Observation,” to learn how the “purpose” of photography has sort of co-evolved with its capabilities over the last couple centuries. There’s a lot to unpack here, but I’ll mainly focus on:

- the concept of “objectivity” and “reliability” in these evolving methods

- how this plays out in typology

Objectivity & Reliability

I like the way this reading describes the shift from photography as a (extremely cumbersome) way of capturing what we see, to a way of allowing us to see new things entirely. In other words, a shift from photography as a method for documentation to a method of perception. By showing us the “un-seeable” we are forced to reconsider entire philosophical frameworks about what is “real” and what is “fake.”

My background in cognitive science makes me particularly interested in the ways in which all of human perception is essentially a lesson in experimental capture – everything we see, feel, hear, smell is an image, passed through the “lenses” on the skin and in the brain into something we can understand. What we experience is not the “real thing” (and many philosophers argue that there is no “real thing” anyway). Lots of people think this is scary. I think this is awesome.

Capture & Typology

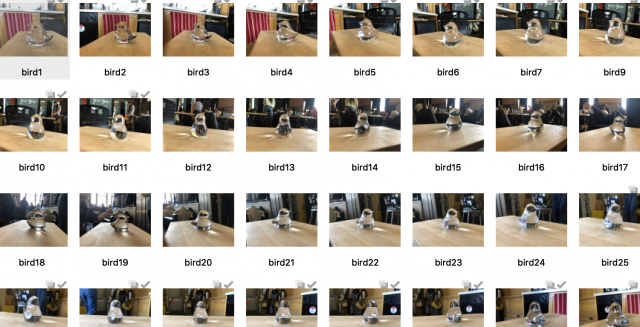

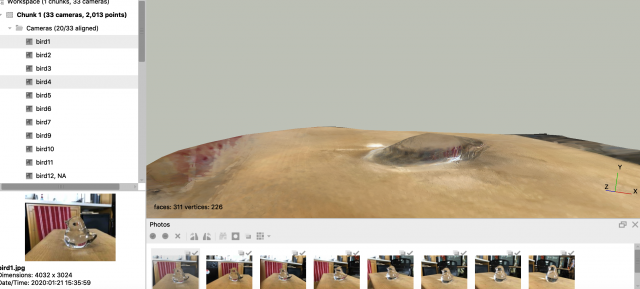

In the latter half of the reading, the author begins to talk about photogrammetry and stitching images together, and then arrives at breaking images apart. This is where typologies really come in.

“The use of the strobe or spark for instance, when applied to photography… is a powerful tool for the isolation of single elements in the stages of motion.”

“[The arrival of] high-speed photography…broke human and animal motion down into finely distinguished moments.

I love this idea of typologies as a way to break something down into more digestible pieces. We see Muybridge’s “Animal Locomotion” of the running horse. This also reminds me of the Time Magazine examples from class, where the artist blacked out everything but the faces on the front page.

This deliberate break-down of gestures, events, and interactions usually taken for granted is an opportunity to reveal things “too small, too fast, too comples, too slow and too far away to be seen with the eye.” I’m curious how this idea can continue beyond the obviously visual and break into our other senses.

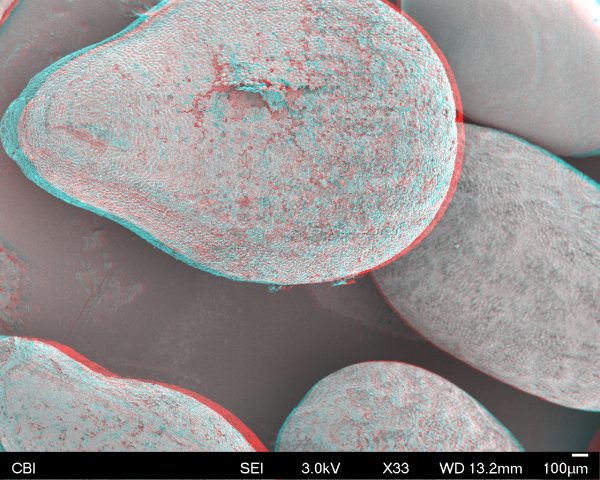

I like how the reading ends. It brings us full circle, describing how “x-ray photography arrived at a time when the reliability of photography was acutely questioned.” This was a time when the impression of photography as an “objective” source of truth was “beginning to wear thin” due to photo editing, staged events, etc. Are we not in a similar place today?

X-rays in this way reconnected the world with the dominant Western, scientific, truth-seeking discourse of the time. We are in an era today where politics, technology, etc. have likewise disconnected us from that discourse. Will we as a society find a “new x-ray” to cling back to that fleeting vision? Or is the discourse simply changing for good (and maybe for the better)?

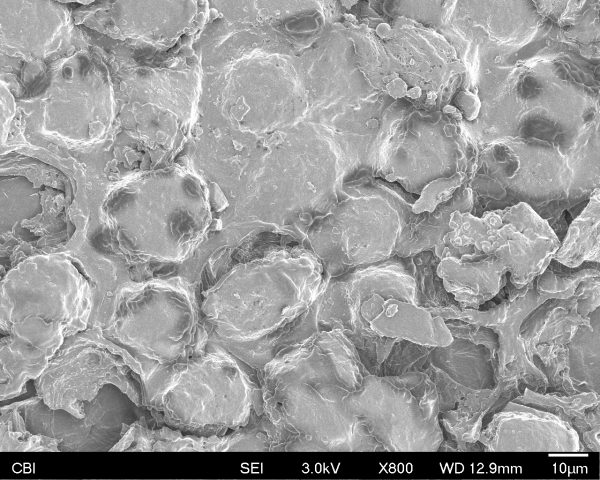

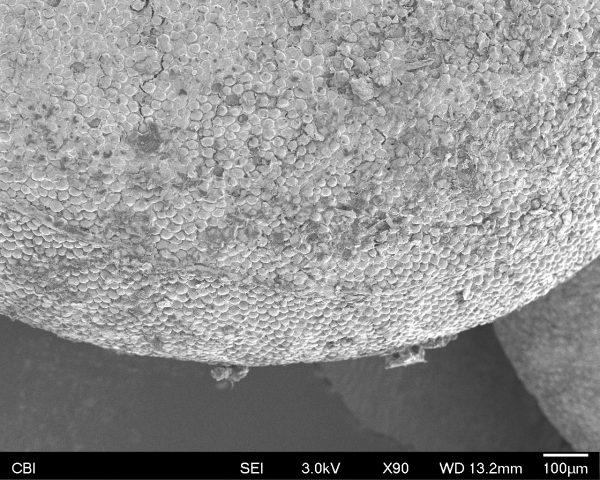

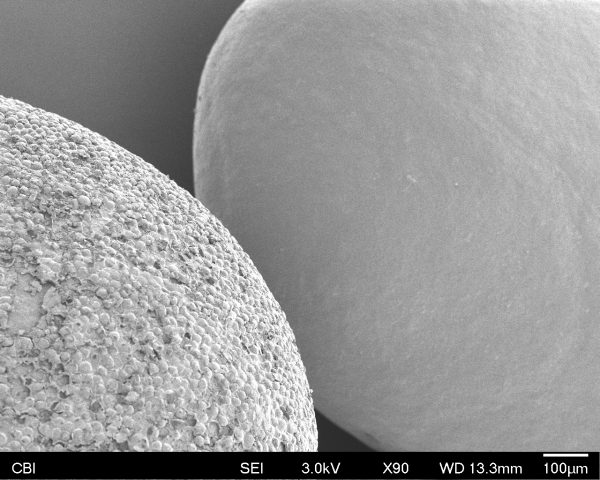

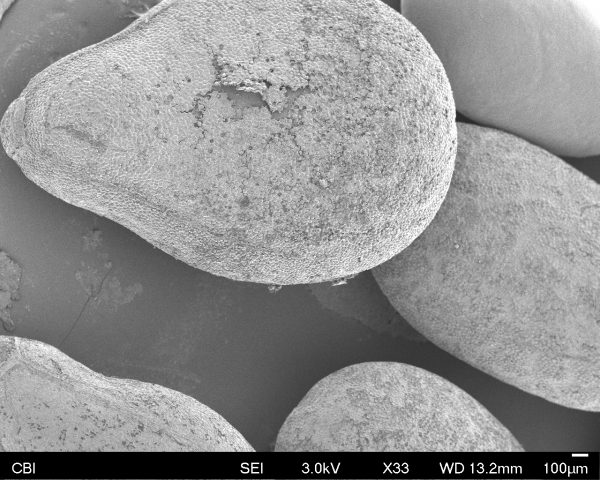

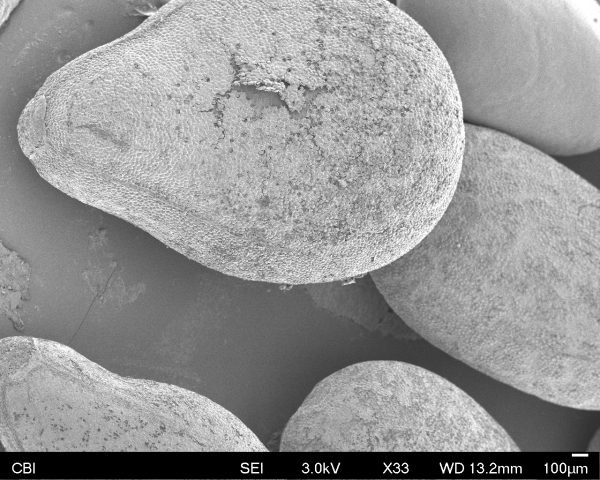

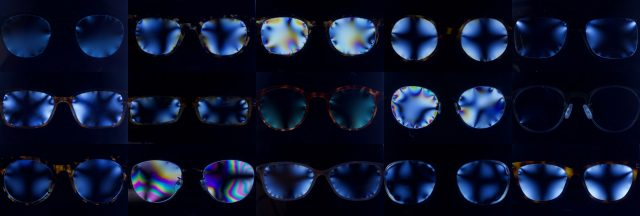

Many people are completely dependent on corrective lenses without knowing how they work; this project examines the invisible stresses we put in & around our eyes every day.

Many people are completely dependent on corrective lenses without knowing how they work; this project examines the invisible stresses we put in & around our eyes every day.