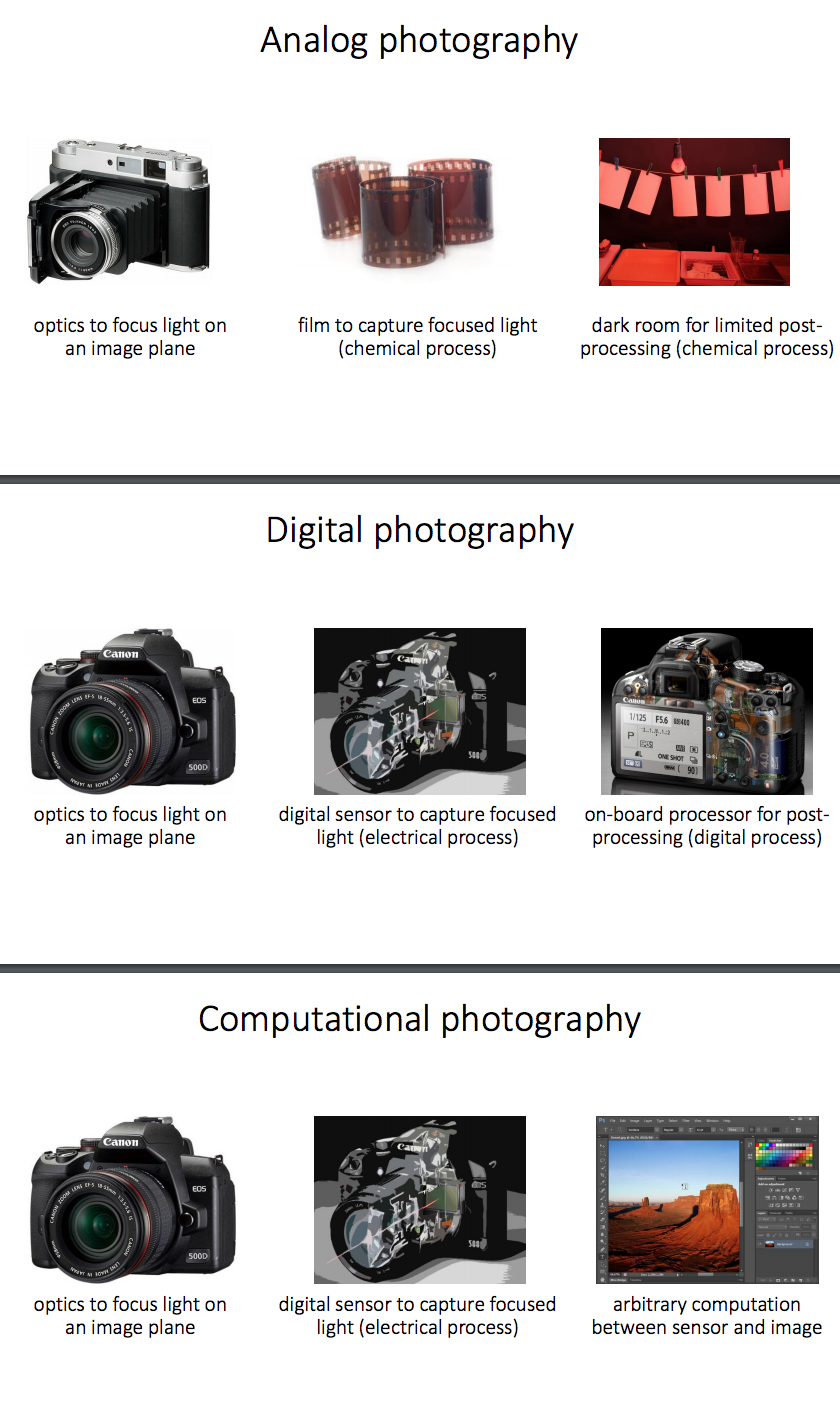

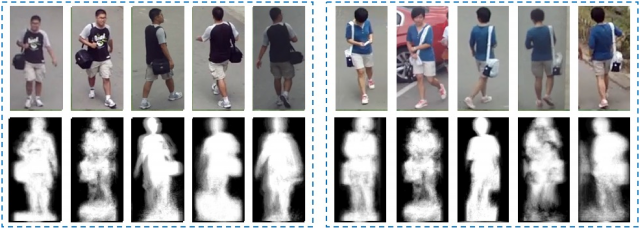

This article made me think about human gait recognition and its use as a a means for biometric identification. This led me to stumble across this paper on free-view gait recognition which is an attempt to solve the problem of gait recognition needing to have multiple views to be effectively measured/identified, and the use of multiple cameras in city-wide security systems to build such identification. So this combination of using security systems and then deploying algorithmic identification to make the specificity of human beings by the ways in which they move through such surveillance systems seems like an act of “nonhuman” photography that arises out of the combination of smaller systems of “nonhuman” photography. So I am interested in what other collisions of “nonhuman” systems of photography can intersect with each other to create unintended image portraits.

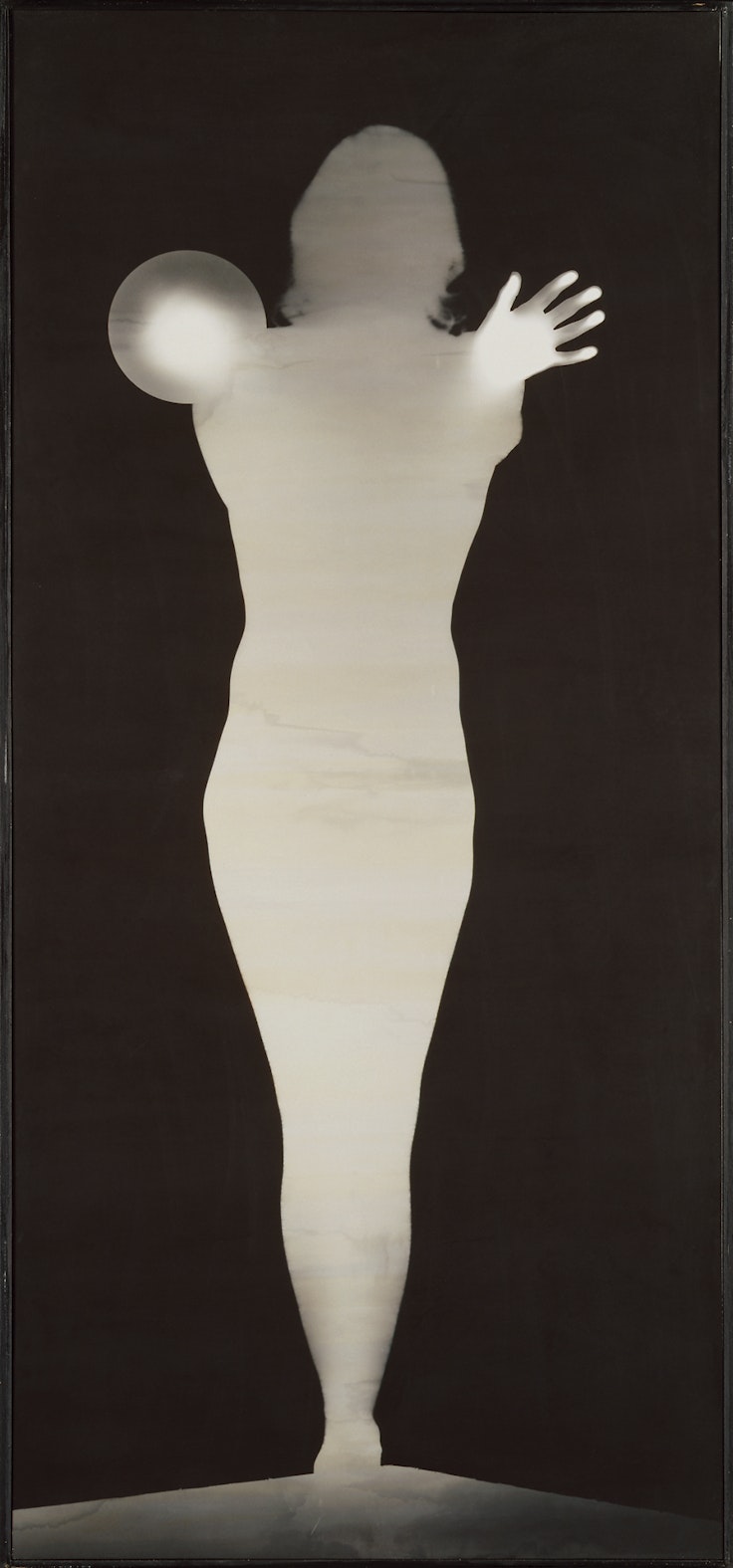

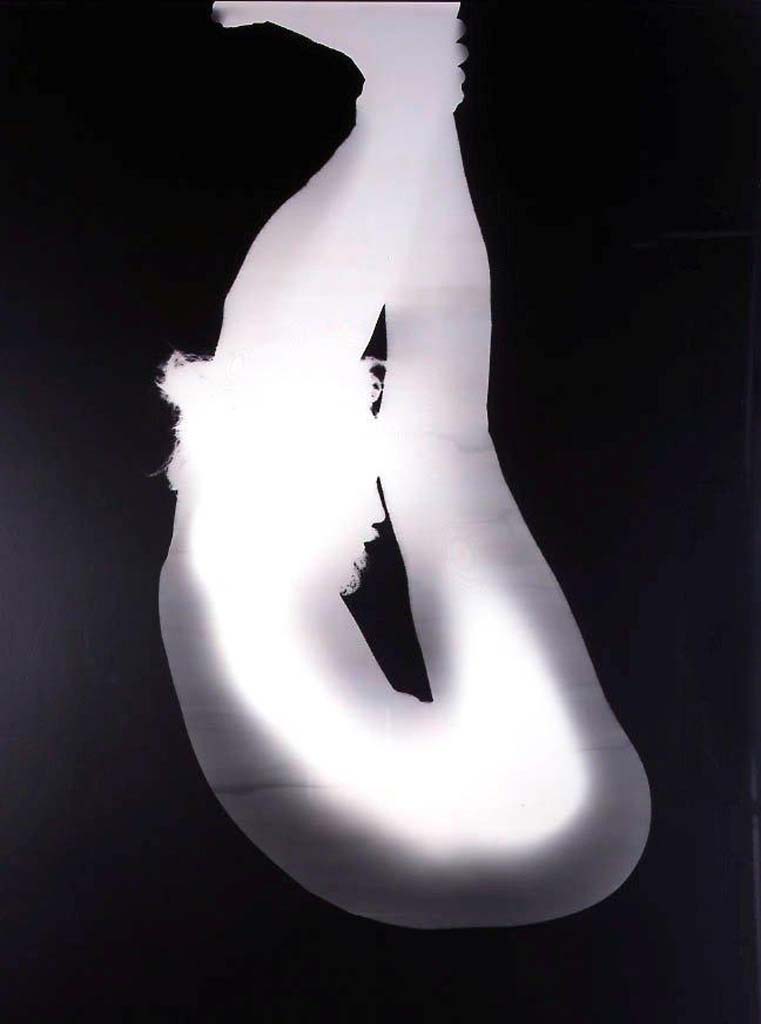

“Nonhuman photography can allow us to unsee ourselves from our parochial human-centered anchoring, and encourage a different vision of both ourselves and what we call the world.” I think that the above example concerned with gait identification is about trying to see something specific, and I am interested in the fragments and detritus that could be created from this (and other systems of collision). For example, in the picture below one can see the images compiled and the lines they create for the gait detection to be accurate, but this for me raises an aesthetic question of what does the imagery needed to identify people via their gate look like. What are the human portraits created out of surveillance and algorithmic identification?