For this project, I (mis)use corporate knowledge transfer methods to make a portrait of my grandfather.

Through it, I get an extremely weird, sometimes unsettling, and usually hilarious point of view on corporate culture.

I’m also able to impose some of my HCI education and push it into a space where it’s not “supposed to go.” I get to see how human-centered design principles (like interview techniques, concept mapping, etc.) hold up against the extremes of the hyper-logical and the hyper-personal.

Background

(In all seriousness) I have one grandparent left, and we’ve gotten closer over the last few years. He expresses some regret over not having been an active part of my childhood (thanks to living on opposite ends of the country). I want to help close this gap, find a way to capture his wisdom, and consider the knowledge-based “heirlooms” he might be passing down.

What do we do in the face of this problem? We turn to the experts. When you google “intergenerational knowledge transfer” or even “family knowledge transfer,” all I found was corporate knowledge transfer methods. What happens if I apply these methods to my family as if it were an organization?

———————-

Method

Method derived from: Ermine, Jean-Louis. (2010). Knowledge Crash and Knowledge Management. International journal of knowledge and systems science (IJKSS). 1. 10.4018/jkss.2010100105.

password: excap20

Phase I: Strategic analysis of the Knowledge Capital.

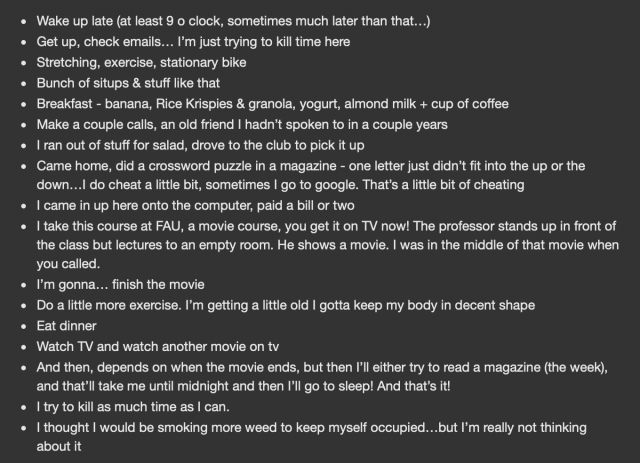

First, identify the Knowledge Capital. One day, I called my grandpa and gathered a list of every single thing he had done that day.

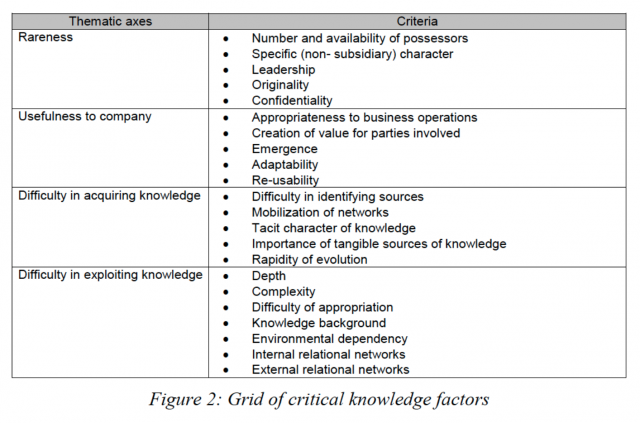

Next, perform an “audit” to identify the knowledge domains that are most critical, by using the following metrics:

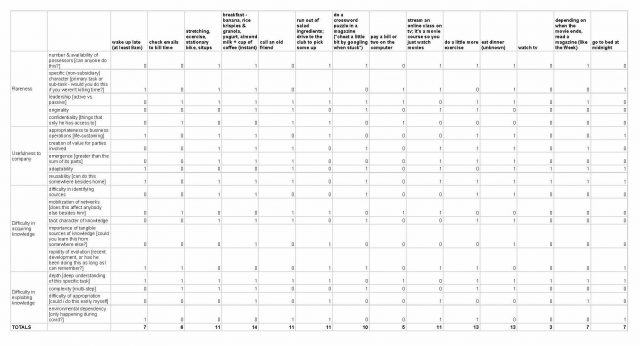

My table (full version here):

The results show that making breakfast is the most critical knowledge domain (with a high score of 14). I’m not surprised at all. It’s an incredibly specific ritual for him – he has been making the same bowl of cereal, 7 days a week, for at least 30 years. It’s in my earliest memories of him (even when he was visiting us in Colorado, we would make sure we had all the ingredients on hand). It’s interesting that the “knowledge audit” managed to capture the salience of this task as well.

Phase 2: Capitalization of the Knowledge Capital.

Now that I know the most important knowledge, I convert the tacit knowledge of how to do it into explicit terms. Or, in other words,

“collect this important knowledge in an explicit form to obtain a ‘knowledge corpus’ that is structured and tangible, which shall be the essential resource of any knowledge transfer device. This is called ‘capitalisation,’ as it puts a part of the Knowledge Capital, which was up to now invisible, into a tangible form.”

As a fun aside, the last line there is essentially the business-speak definition of “experimental capture” – bringing something that was invisible into tangible form.

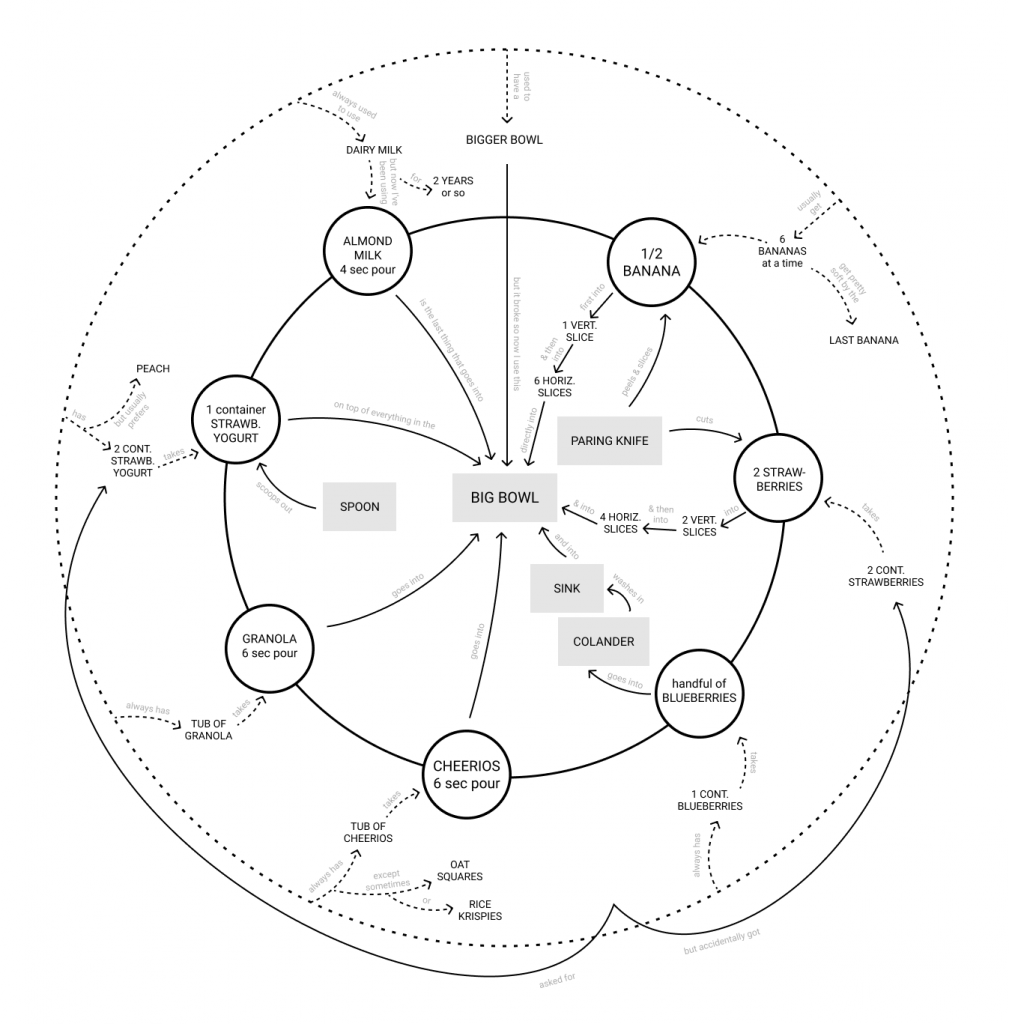

To “capitalize the knowledge capital” (not a joke – this is what it’s actually called), the literature calls for the use of “graphical models,” and give several examples such as the phenomena model, activity model, concept model, task model, and history model.

Before making the model, it’s important to interview the stakeholders. I relied on interview techniques from my research background, as well as some inspiration from Rachel Strickland’s Portable Portraits, and conducted a contextual inquiry over FaceTime where I asked my grandpa to walk me through making breakfast in excruciating detail. (Arguably the hardest part of this whole capture was remotely helping a 89-year old figure out how to flip the camera view 🙂 ).

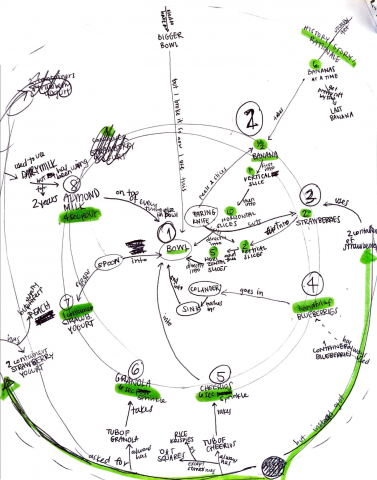

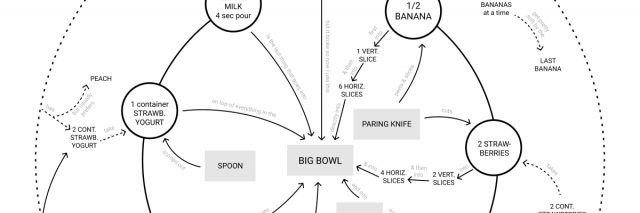

Next, as I am the knowledge corpus (literally), I needed to convert the tacit knowledge I had learned into an explicit model. I chose to make a concept map.

Concept maps appear not only in the KM literature but also in my HCI curriculum. Each field has a slightly different definition, but overall, concept maps are meant to be highly structured & methodical to articulate a user’s mental model in a specific situation. Each element in the map must be a noun, and every arrow must be a verb.

Counterintuitively, it’s the constraints that allow strong stories to emerge. We are taught this in HCI, and I am really taking that and pushing it to the limit here. To what extent can I tell a hyper-personal story within the strict constraints of a concept map?

Phase 3: Transfer of the Knowledge Capital

I completed a capture for one specific task. The next step would be to repeat this capturing-and-modeling process for a whole series of critical knowledge domains. With all the models together, the organization goes on to create a “Knowledge Book” (or “Knowledge Portal” if it’s online) where it can be disseminated to new employees.

reflection

Beyond having some fun with corporate literature, using (or mis-using) these highly structured tools are an opportunity for me to critique my academic background. I don’t get a lot of opportunities to do this, so I loved being able to push up on the edge of user research tactics in ways that would probably not fly in my career.

I often struggle to position myself within my field and feel generally suspended between art, design, and tech. This project was not incredibly profound or anything, but it was a way of placing myself directly between two emotional extremes and sort of navigating that ambiguous space, all within the nice constraints of a single quotidian task.

Some “making of” content: