Zapotec rugs are traditionally handmade and wool-woven in a foot loom in the village of Teotitlan del Valle located just outside of Oaxaca City in Mexico. The The Zapotecs surrendered peacefully to the Spainish like most cities in the Central Valley, and foot-looms and sheep wool were integrated into Zapotec culture which allowed them to create bigger and bulkier rugs and tapestries. Teotitlan’s weavings became internationally famous in the 1950’s with the arrival of foreign tourism. As sales rose, entire families became involved in the weaving process and the community shifted from predominantly farming to weaving. In the present day, there are still many artisan families the carry on this tradition of producing hand woven rugs and specializing in natural dyes.

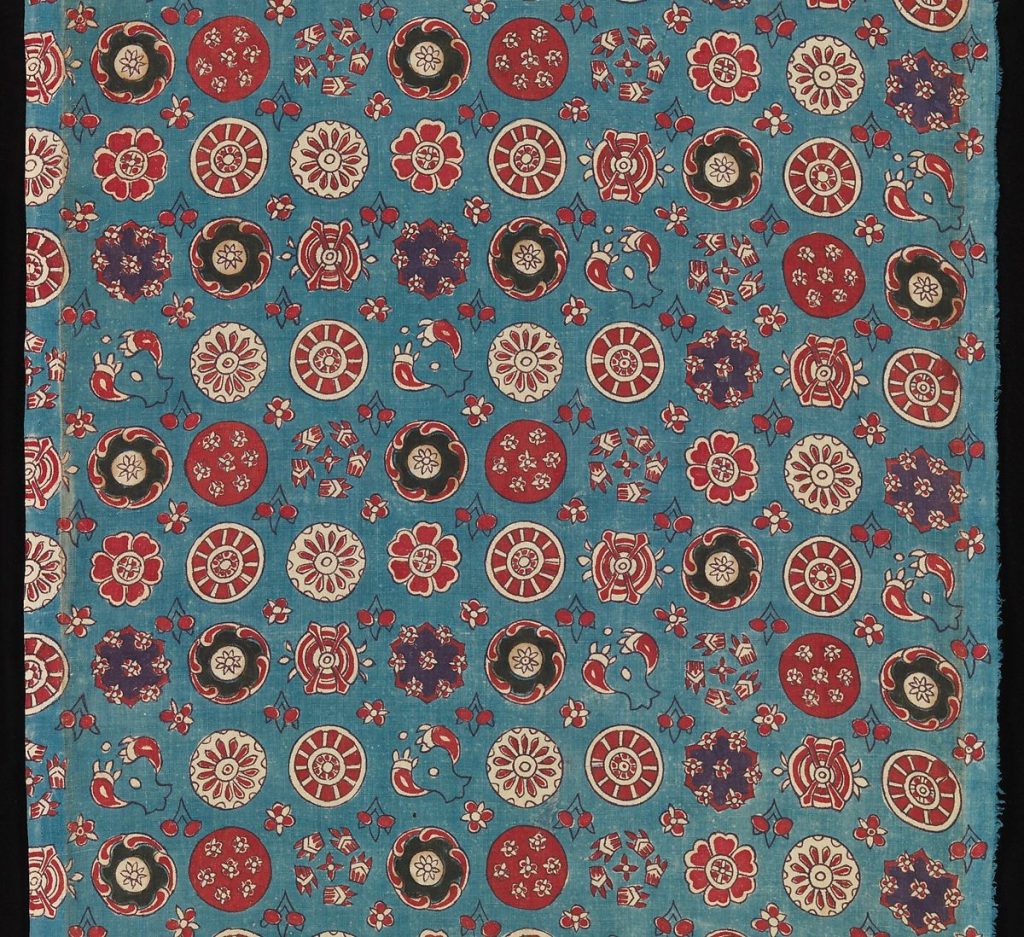

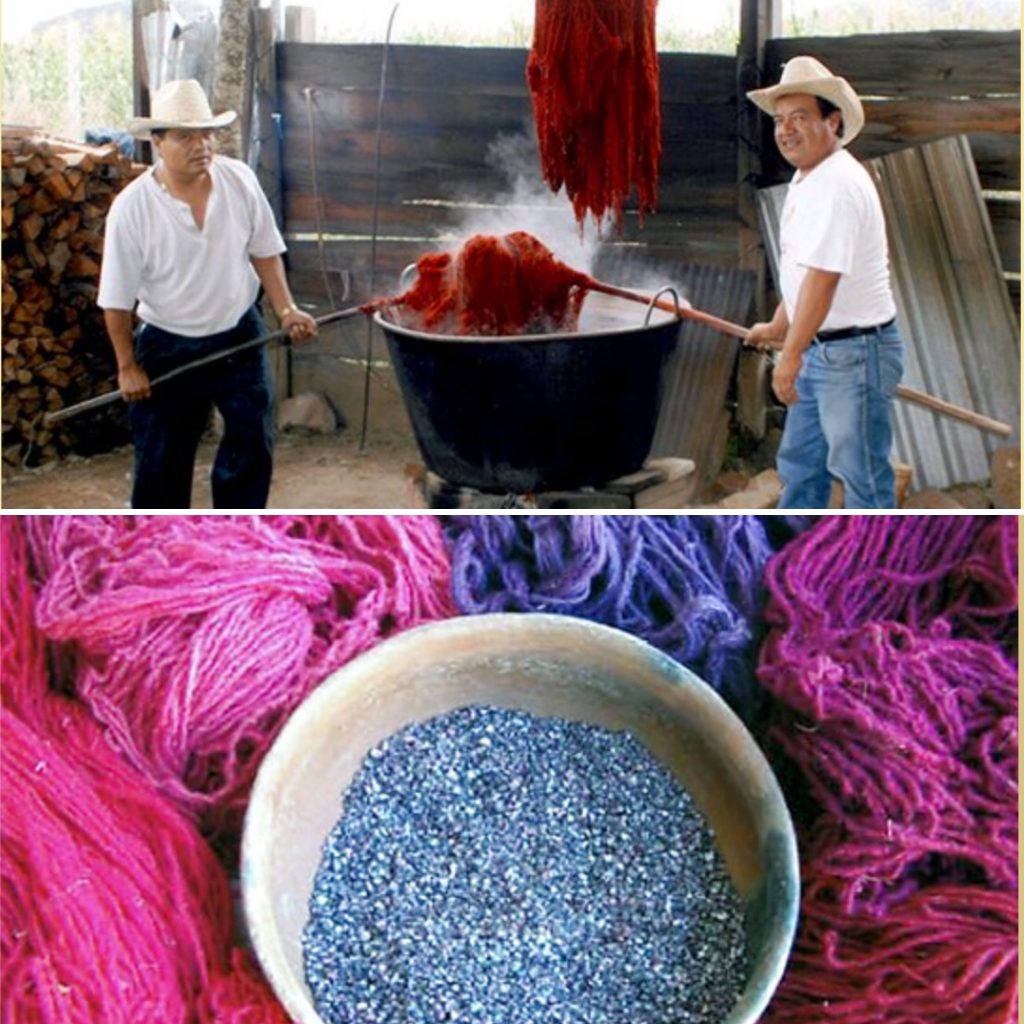

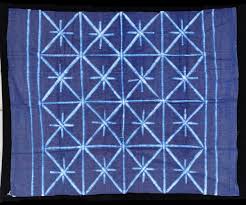

One of the most notable characteristics of Zapotec rugs are the rich colors. The Central Valley is rich in vegetal and animal dyes, and the Spanish brought along salts and oxides that are used as a color toners and fixatives to enrich native natural dyes. With the natural dye workshop coming up, I was drawn to this particular traditional textile. The dyeing process is long and involved, but it’s also cooperative, and the results are stunning.

Among the natural dyes available in Oaxaca, the cochineal is the most renowned. The cochineal is made from an insect that lives and feeds on cacti and produces carminic acid which can be extracted from its body and eggs to make carmine dye.

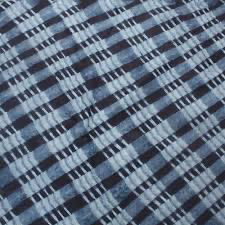

Other classic natural dyes used to color the wool include: the cempasuchil flower for yellow shades, indigo for blue hues, pecan bark and walnut husks for brown, and huisache pods for black. Natural acids (lemon juice for example) and heat are also strategically used to draw out the desired shade of color for the dyed wool.

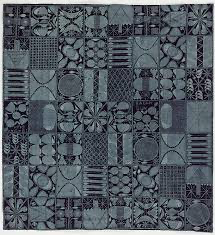

Zapotec rug patterns are drawn out beforehand, and traditional patterns feature glyphs, fretwork animals, and idols taken from the archeological remains of the village church. The designs represent Teotitlan’s history and culture, and overtime, they have even come to incorporate Navajo patterns or reflect famous paintings. Zapotec rugs are a statement piece and testimony to family and history.

References:

https://www.mexican-folk-art-guide.com/zapotec-rugs.html#.X4XRPhNKiYU

https://www.monarchandmallard.com/notes-from-the-road/handwoven-rugs-of-oaxaca

.jpg)