Graham Murtha

Section A

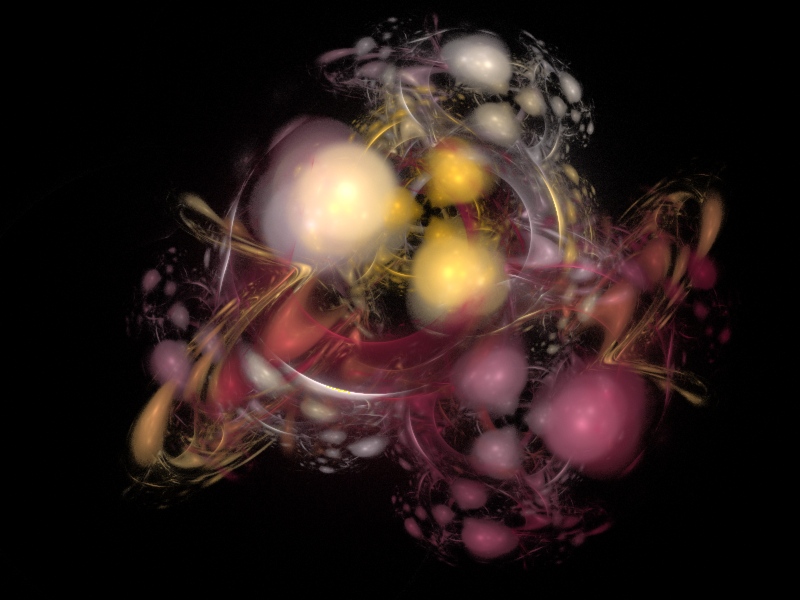

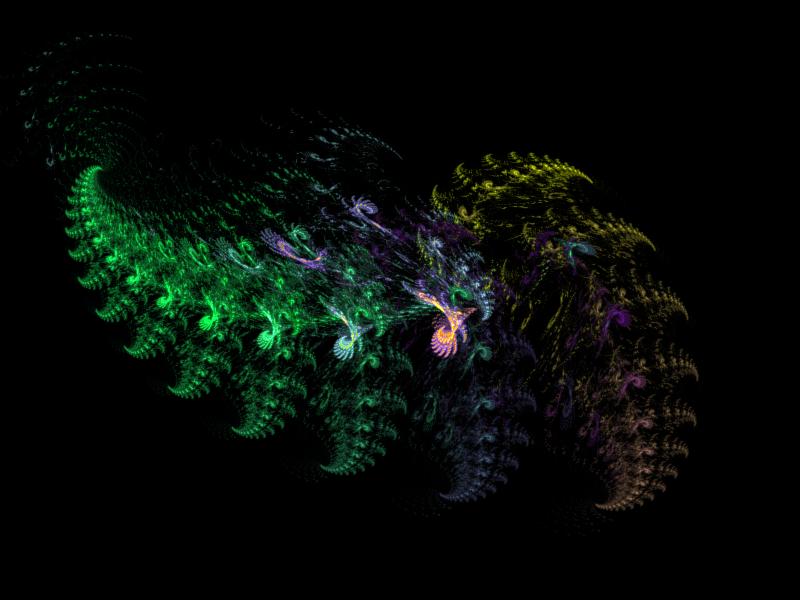

The randomly generated computational art that I looked into this week is called the “Gallery of Randomly Generated Flames” by JWidlfire, an independent artist/blogger. This German artist uses T.I.N.A, a electronics design software by DesignSoft, to generate a series of randomly generated images that all include some depiction of a flame. The flames are generated through a series of random sin/cos waves, arrays, string art, and lighting effects, all with a black background. What I find particularly fascinating about this exhibition is the sequential nature of it, since we know that these 64 different images come from one identical code. The differences in each image are drastic, and yet at the sametime there is a strong visual acuity and pattern througout all 64 pieces. Even some of the flames that look almost biomorphic share commonalities with flames that appear gaseuous. By depicting all different variations in this series, JWildfire demonstrates to us how randomness can provide massive variety, while at the same time preserving certain biases or qualities.

![[OLD SEMESTER] 15-104 • Introduction to Computing for Creative Practice](../../../../wp-content/uploads/2023/09/stop-banner.png)