Asemic Writing

Asemic writing is a wordless open semantic form of writing. The word asemic means “having no specific semantic content,” or “without the smallest unit of meaning.” With the non-specificity of asemic writing there comes a vacuum of meaning, which is left for the reader to fill in and interpret.

Asemic writing explores the liminal territories between familiarity and chaos, language and gesture.

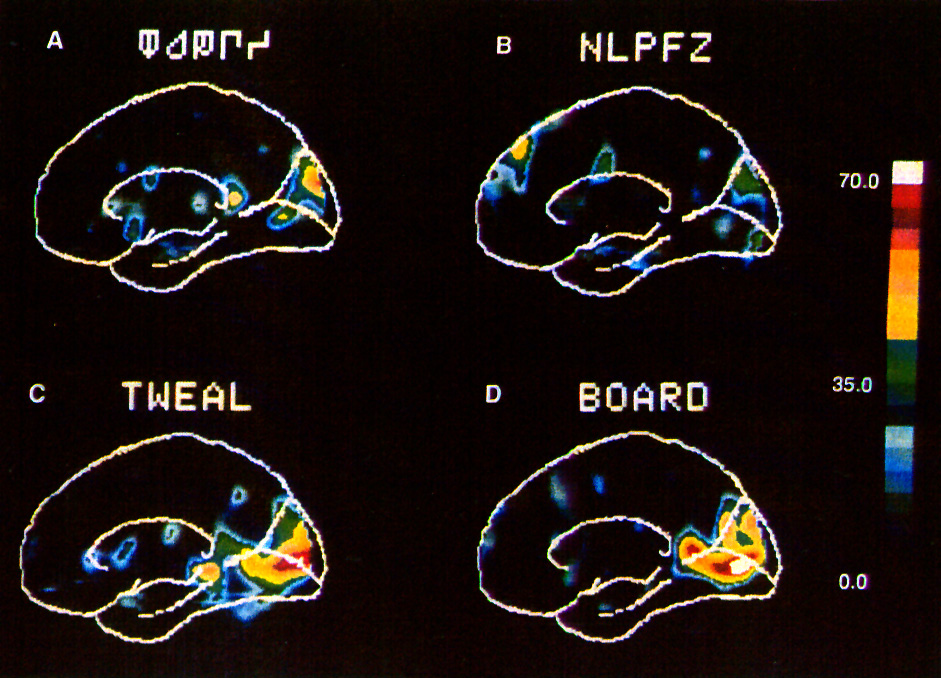

This is research by S.E. Petersen (1995), showing activation of the cortex by “word-like stimuli” including what she called “false fonts”, or letters from an imaginary alphabet.

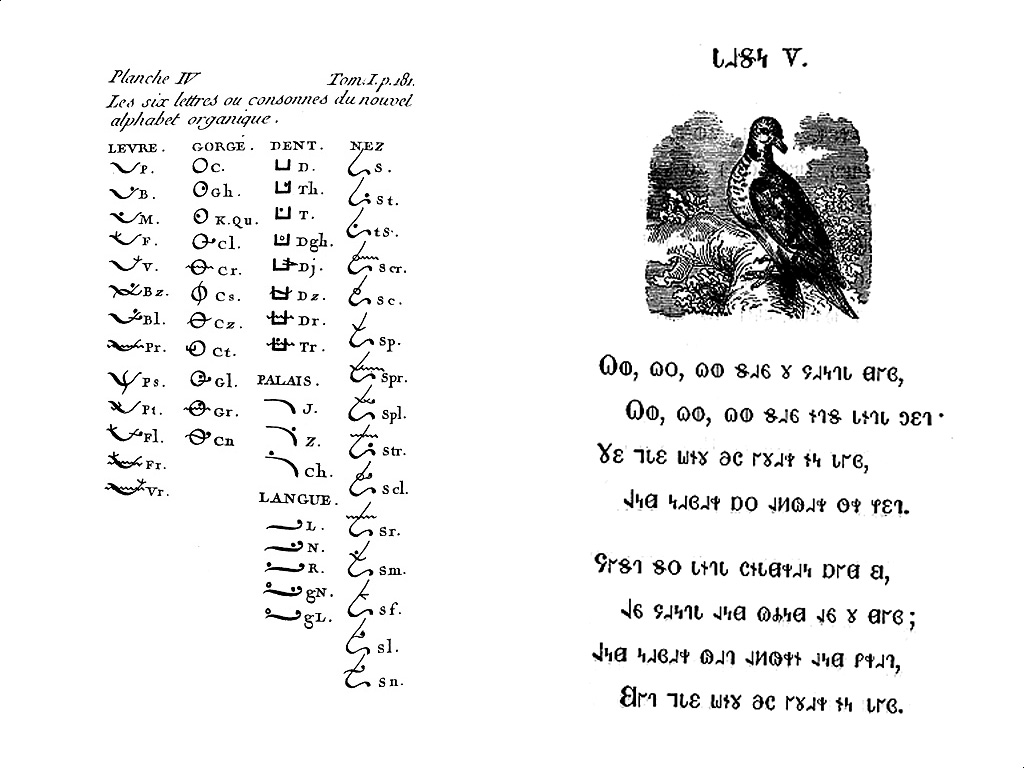

Alphabet Organique (France, 1780s); Deseret Alphabet (1847-1854)

Hélène Smith’s “Martian”:

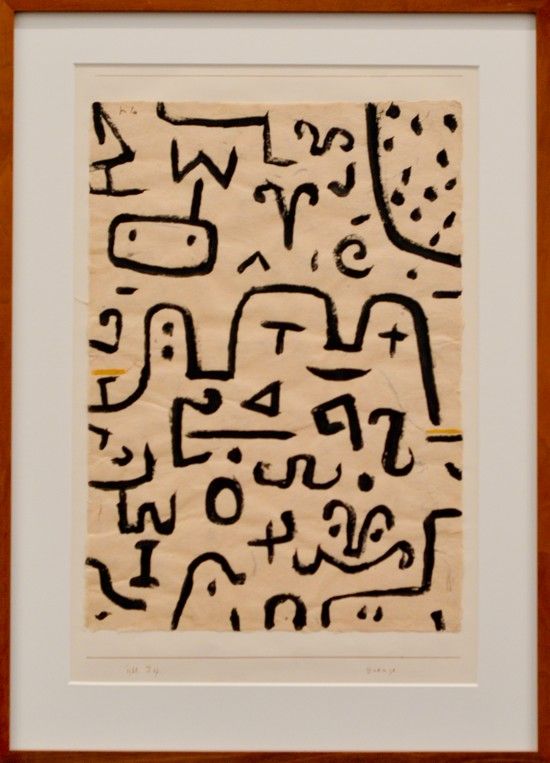

Paul Klee, Frontière (1938)

Joan Miro: surreal writing (1940s);

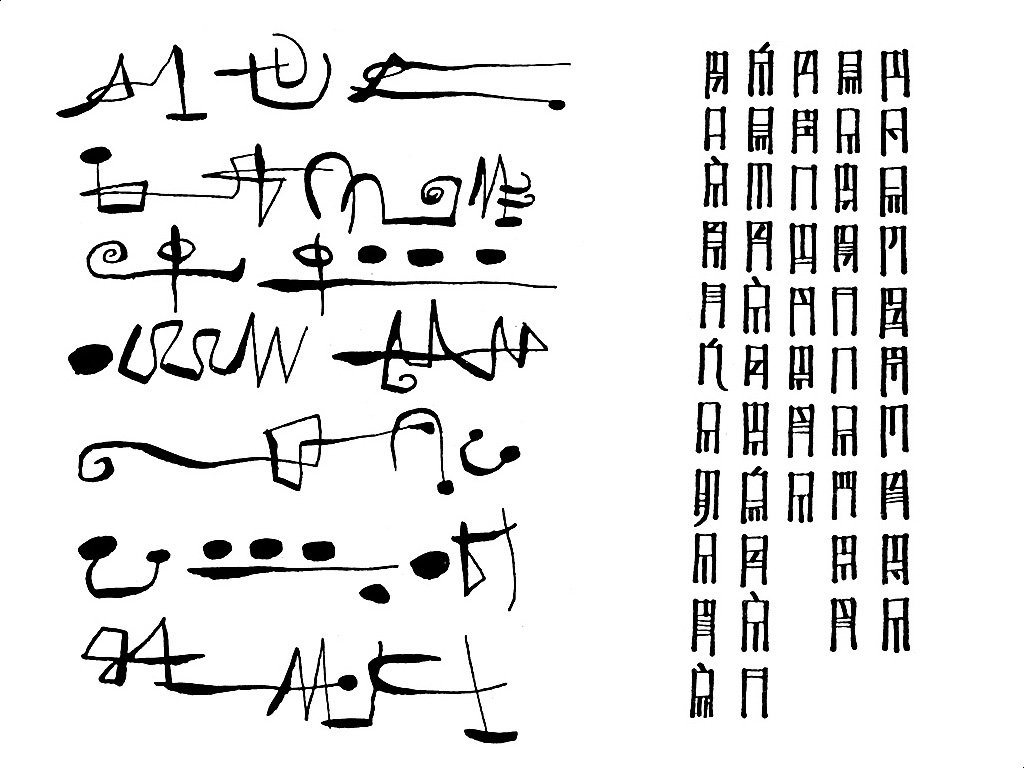

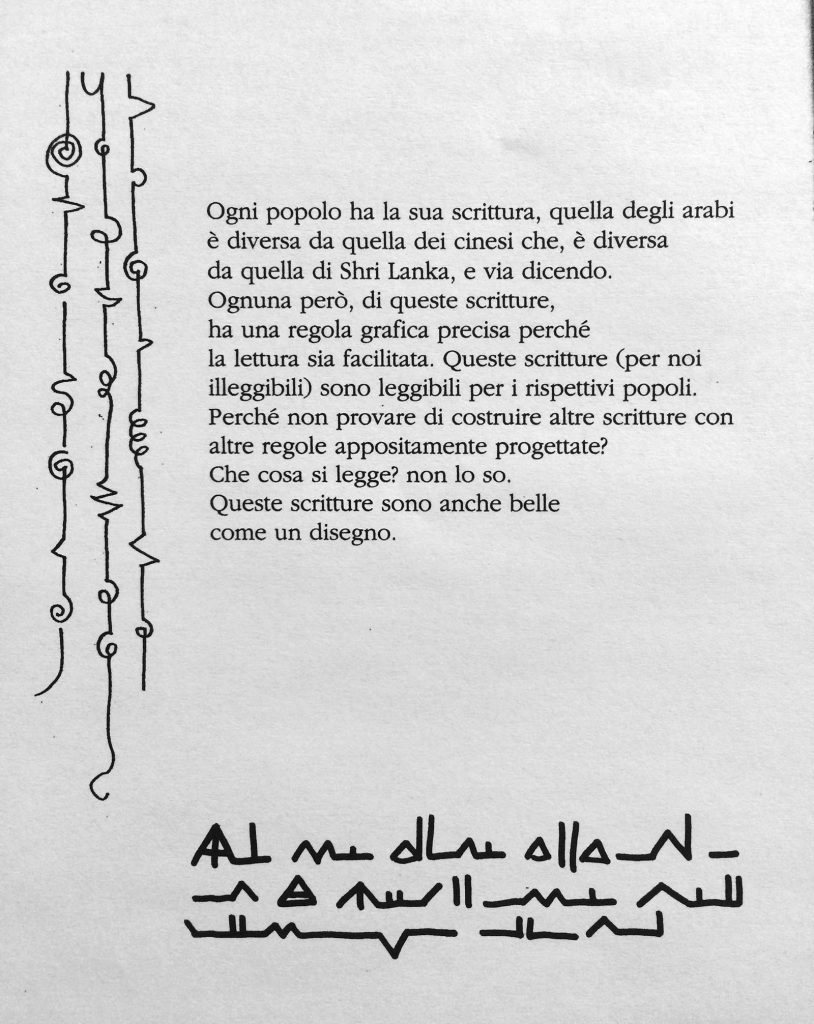

Bruno Munari, Scritture Illegibili di popoli Sconosciuti (1940s)

Munari: “Every people has its own writing, that of the Arabs and different from that of the Chinese, which is different from that of Sri Lanka and so on. However, each of these scriptures has a precise graphic rule for reading to be facilitated. These writings (for us illegible) are legible for the respected peoples. Why not try to construct other systems with other specially designed rules? What do you read? I do not know. These scriptures are also as beautiful as a drawing.”

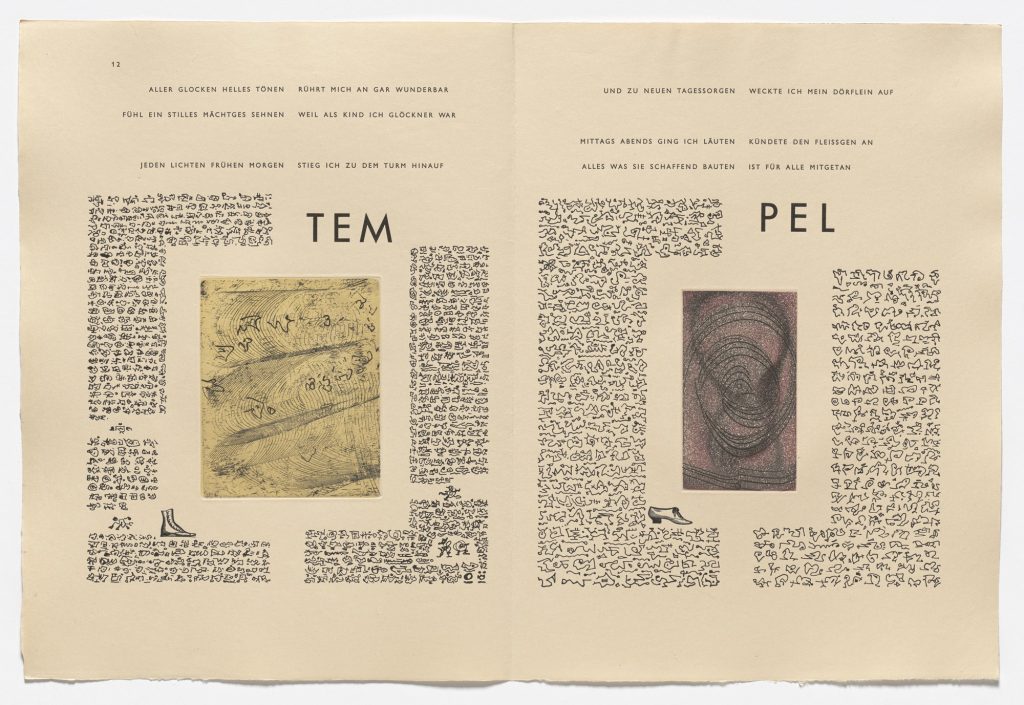

Max Ernst, “Maximiliana ou L’Exercise illégal de l’Astronomie” (1964)

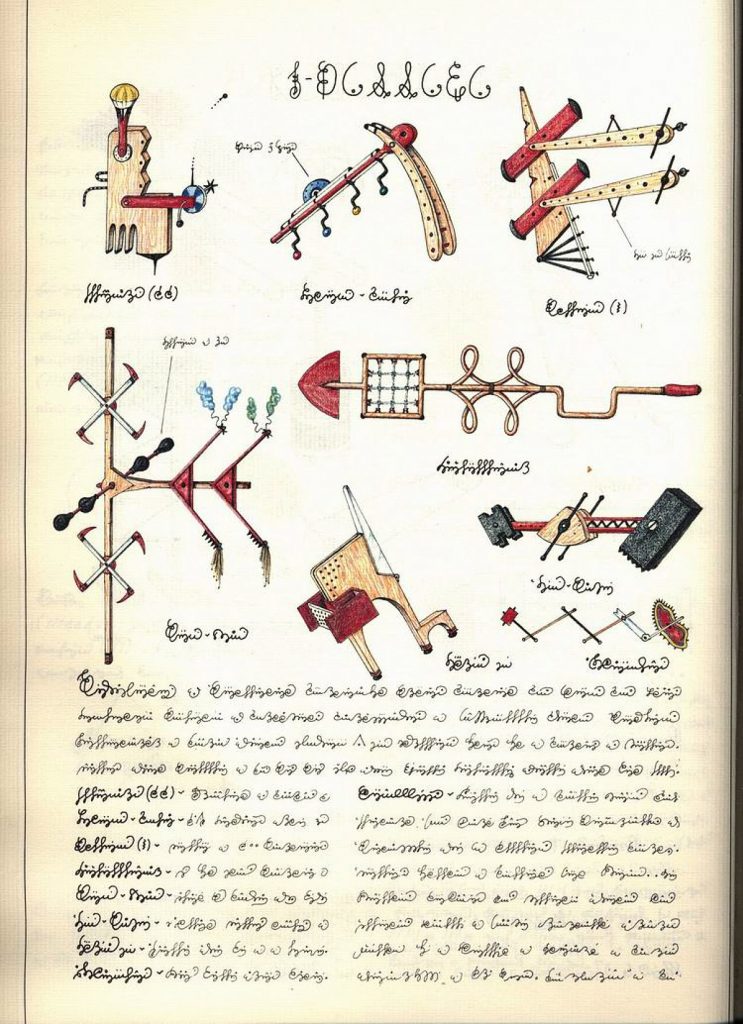

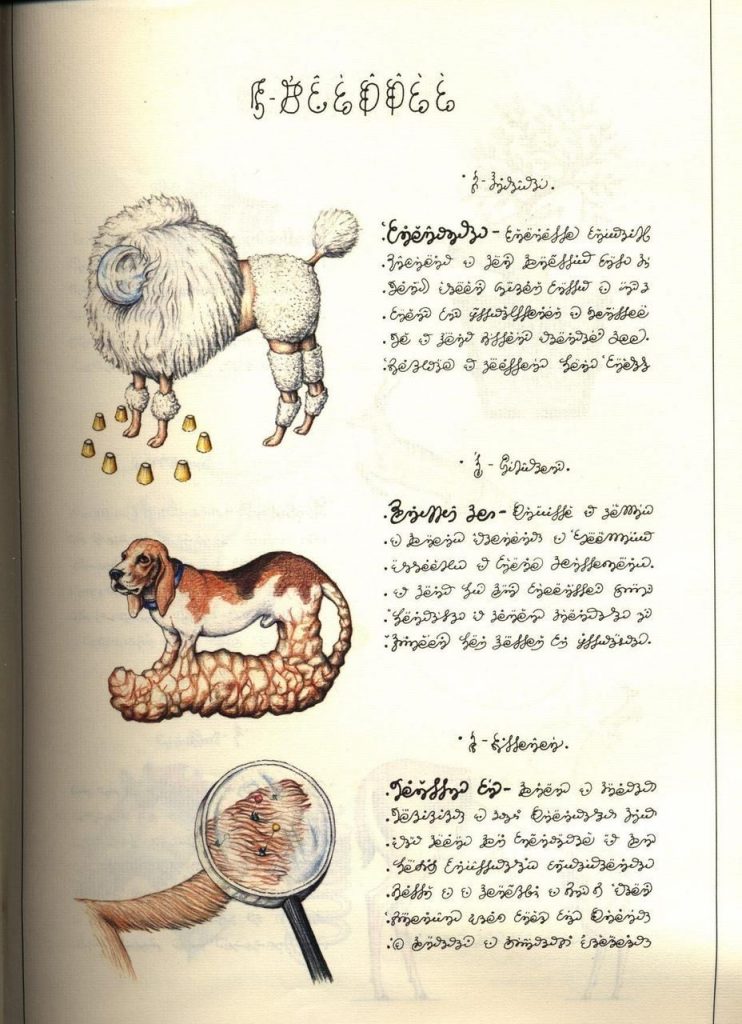

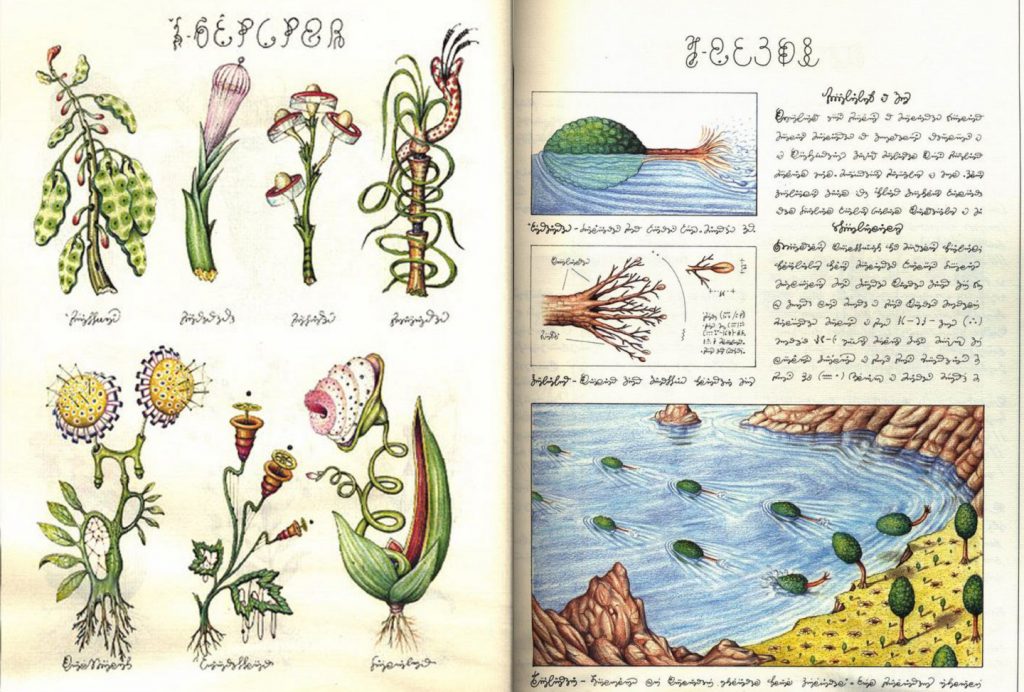

Luigi Seraphini, Codex Seraphinianus (1981)

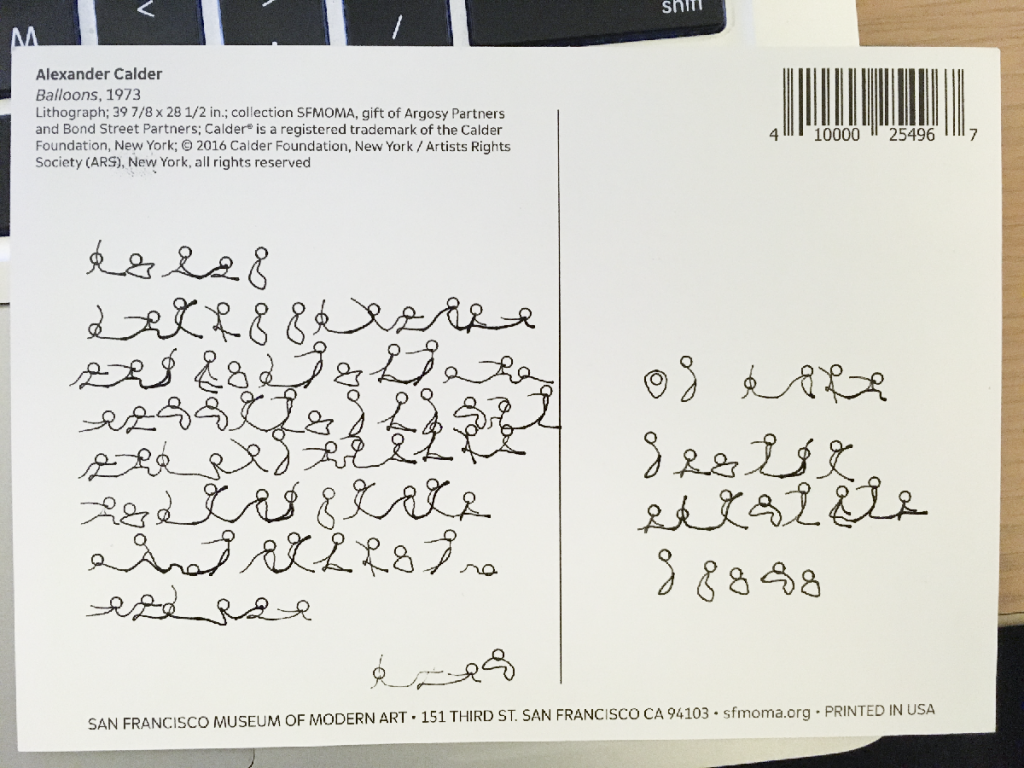

Alexander Calder, Balloons (1973)

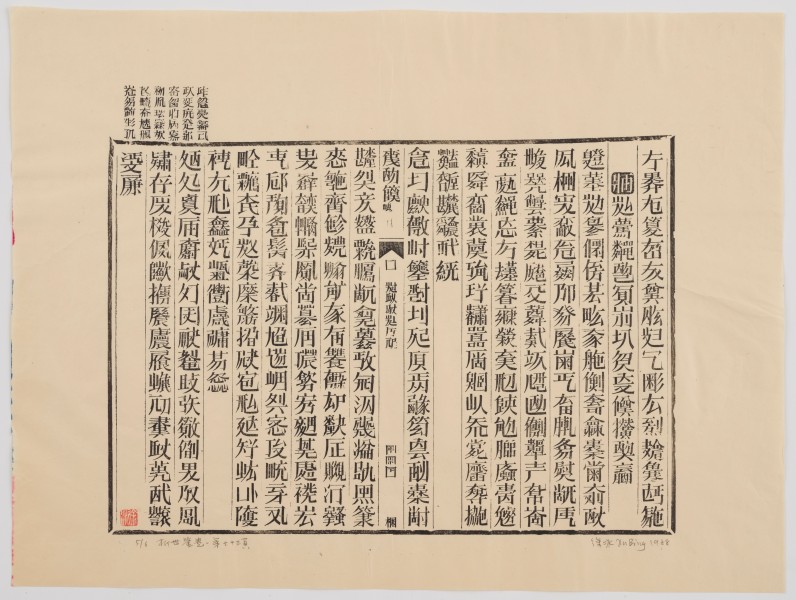

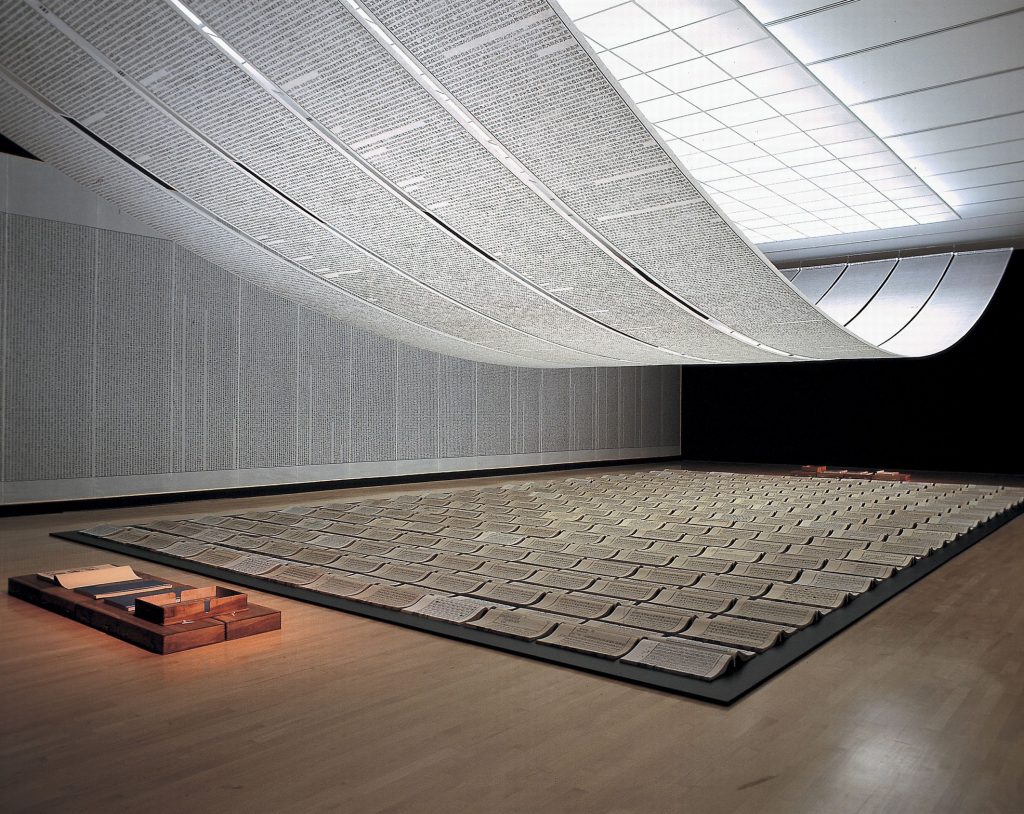

Xu Bing, A Book from the Sky (1987-1991)

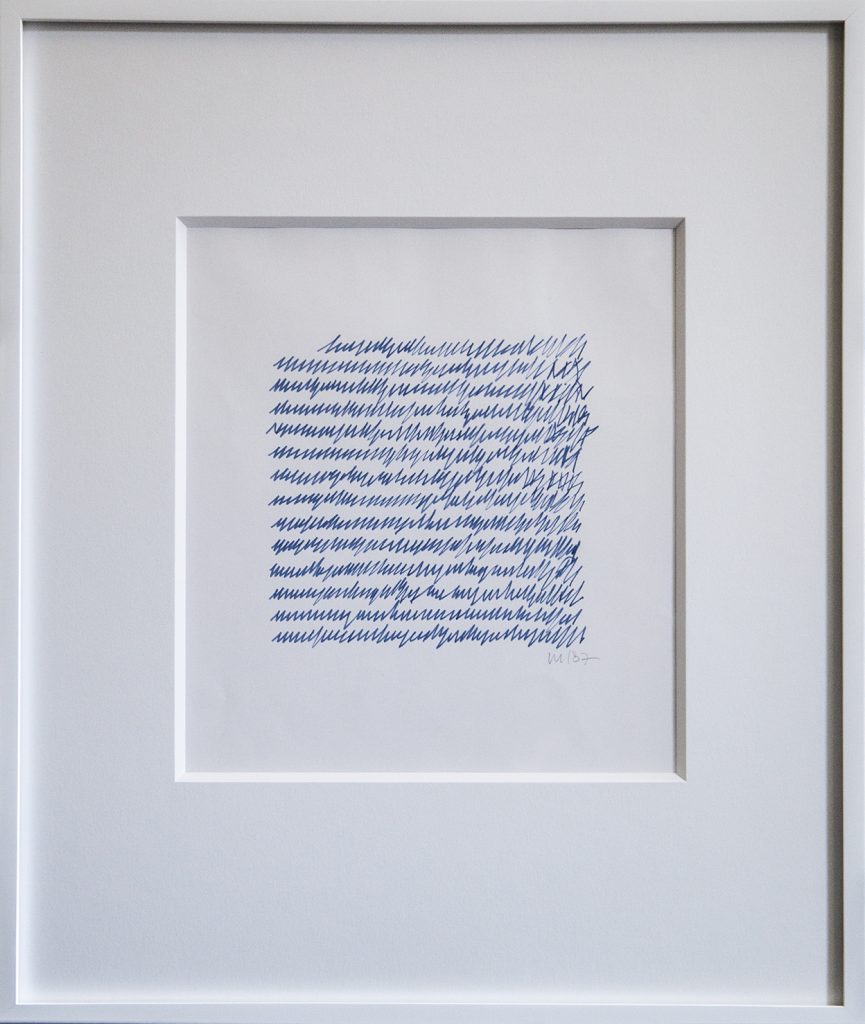

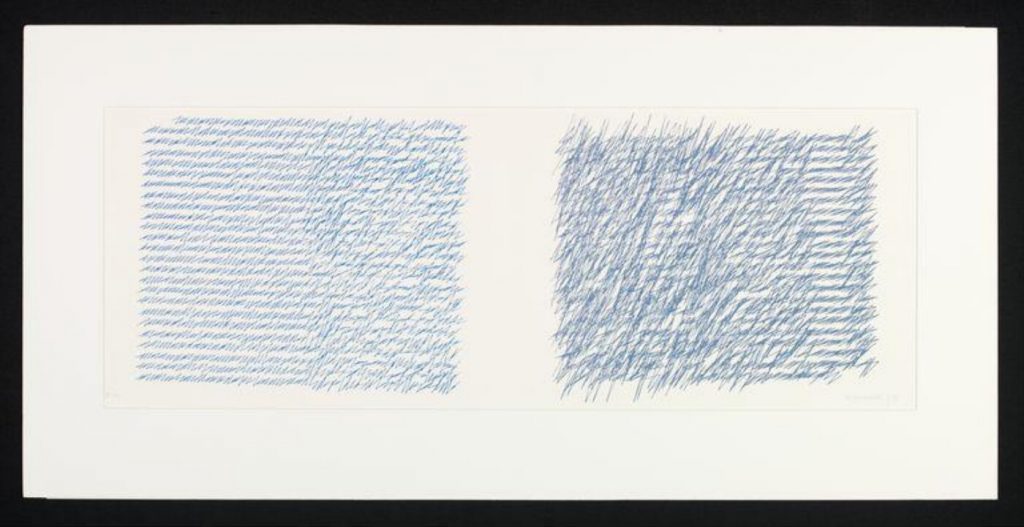

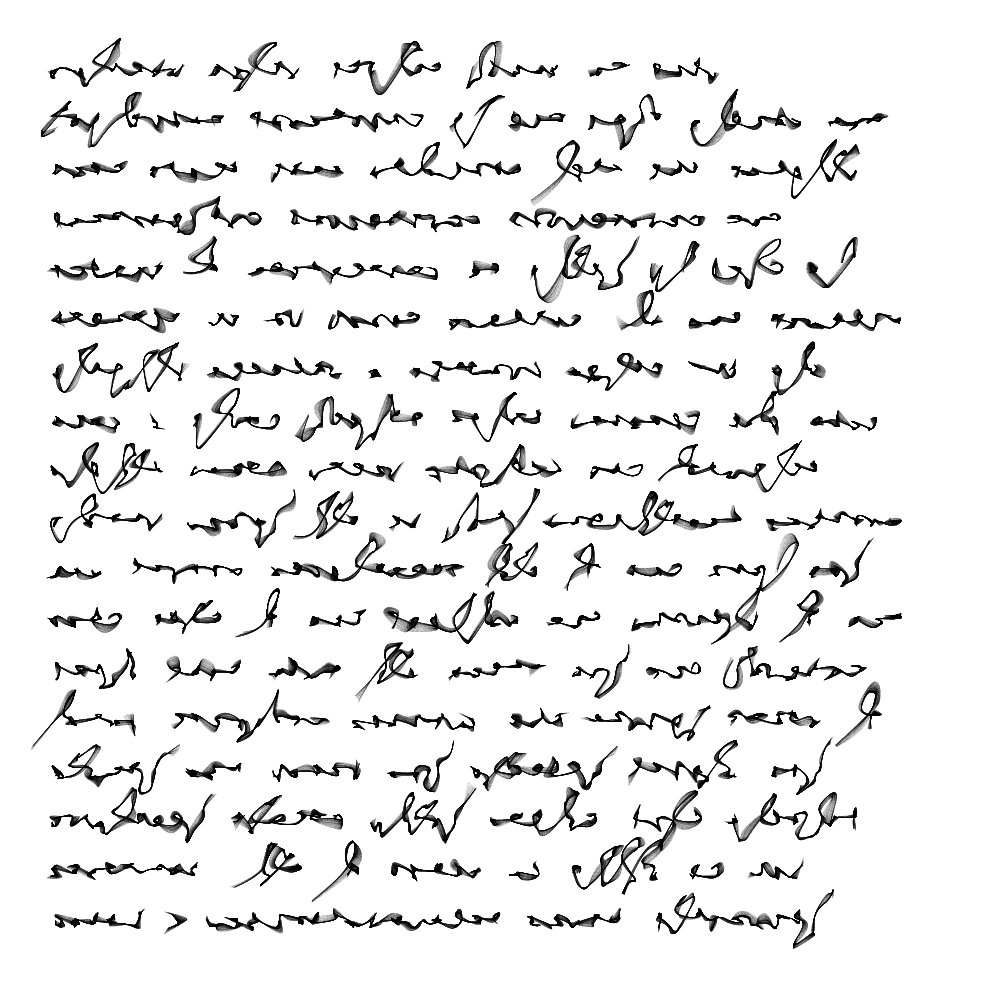

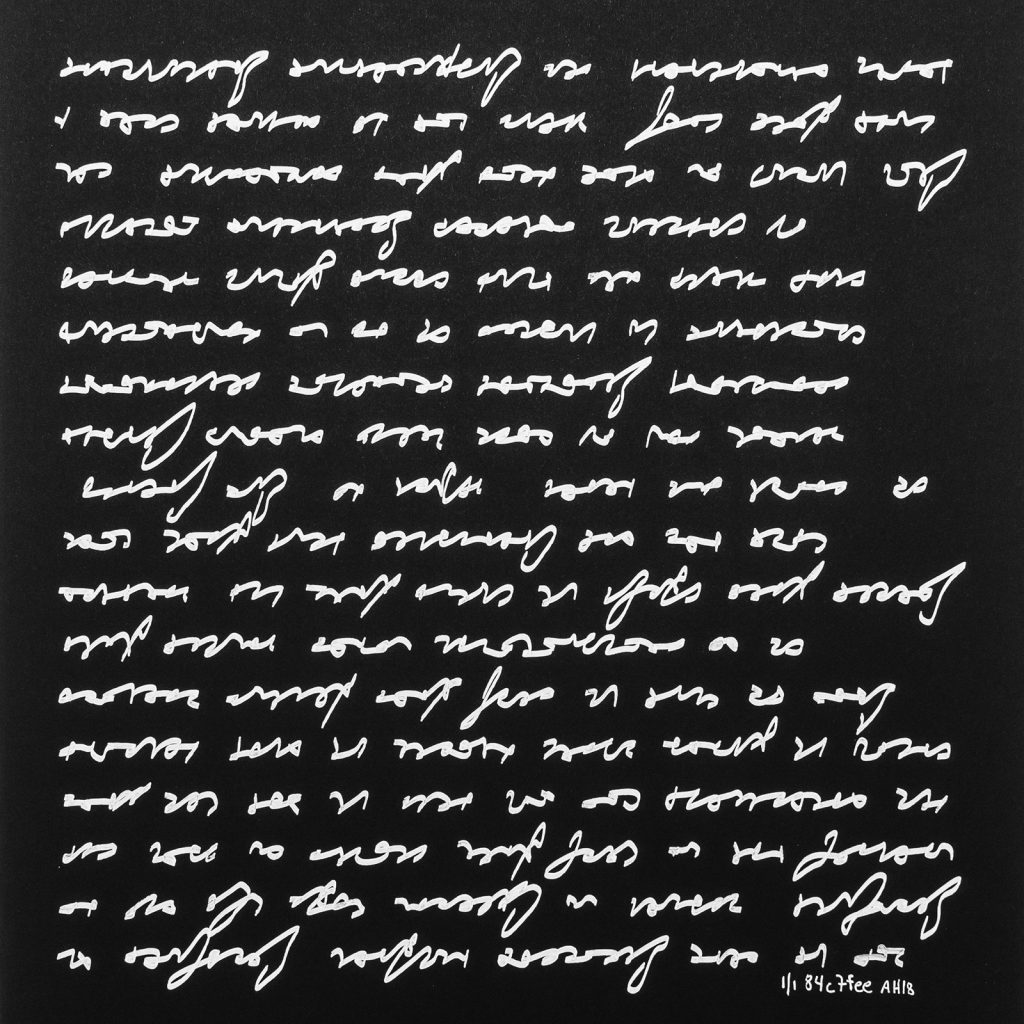

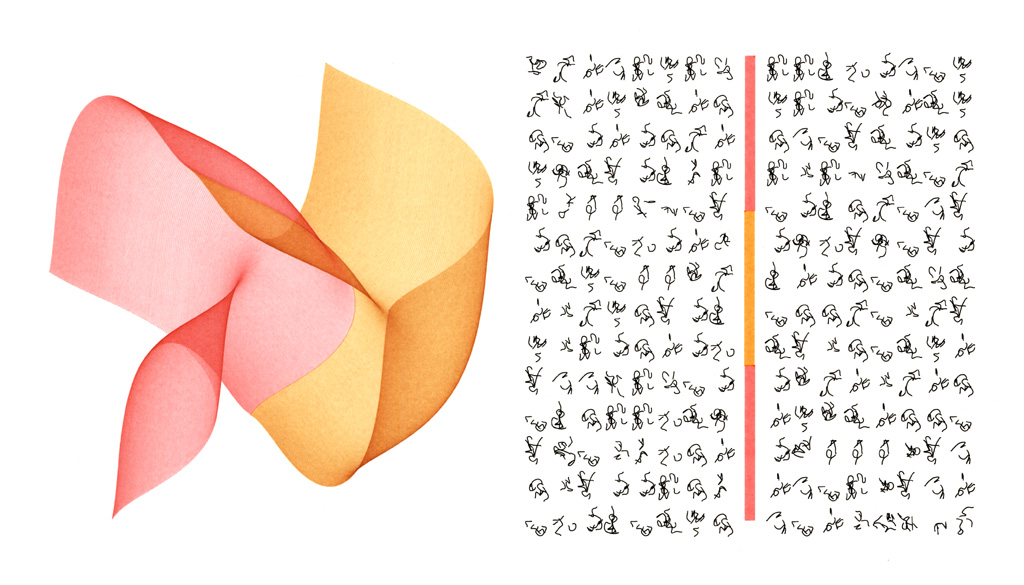

Vera Molnar, Letters from My Mother (1987-88) [more information]

Vera Molnar first started to use computers in 1968. This screenprint was created from two plotter drawings that simulate the handwriting of Molnar’s elderly mother as she became increasingly unwell. In a description of the work, Molnar wrote:

“My mother had a wonderful hand-writing. There was something gothic in it (it was the style of writing of all well-educated ladies in the Habsburg monarchy in the early XXth century) but also something hysteric. The beginning of every line, on the left side, was always regular, severe, gothic and at the end of each line it become [sic] more nervous, restless, almost hysteric. As the years passed, the letters in their totality, become [sic] more and more chaotic, the gothic aspect disappeared step by step and only the disorder remained. Every week she wrote me a letter, it was a basic and important event in my visual environment. They were more and more difficult to decipher, but it was so nice to look at them… then, there were no more letters…So I went on to write letters of hers to myself, on the computer of course, simulating the transition between gothic and hysteric.”

Many of Molnar’s other works also resemble writing.

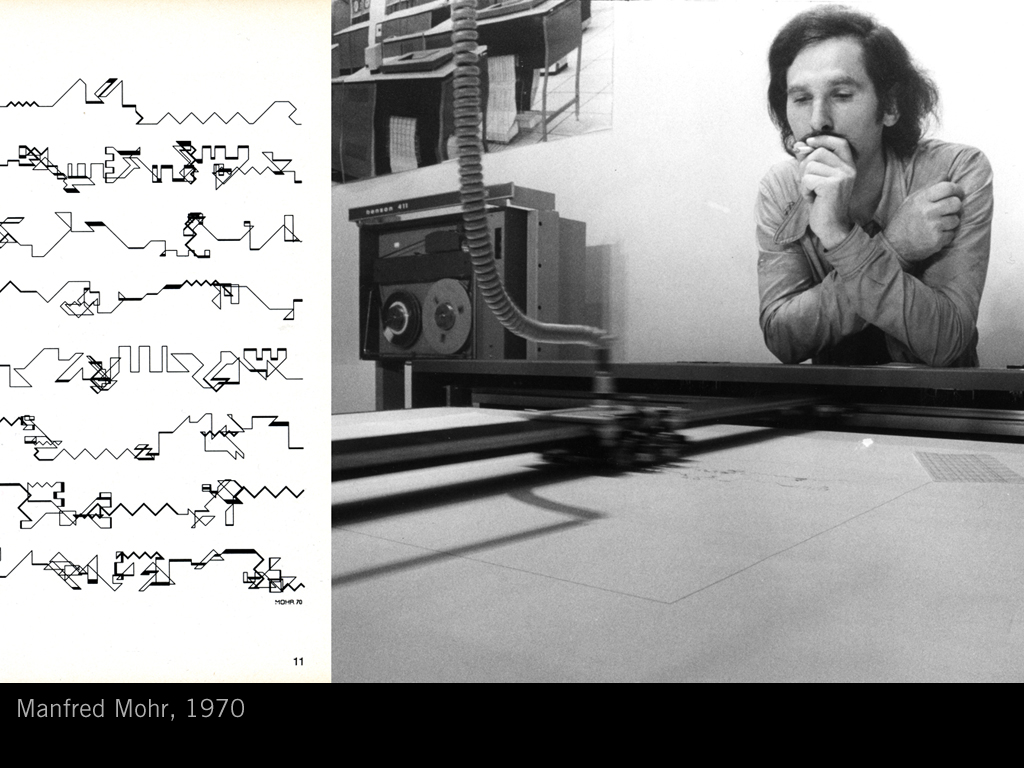

Manfred Mohr, another early computer artist:

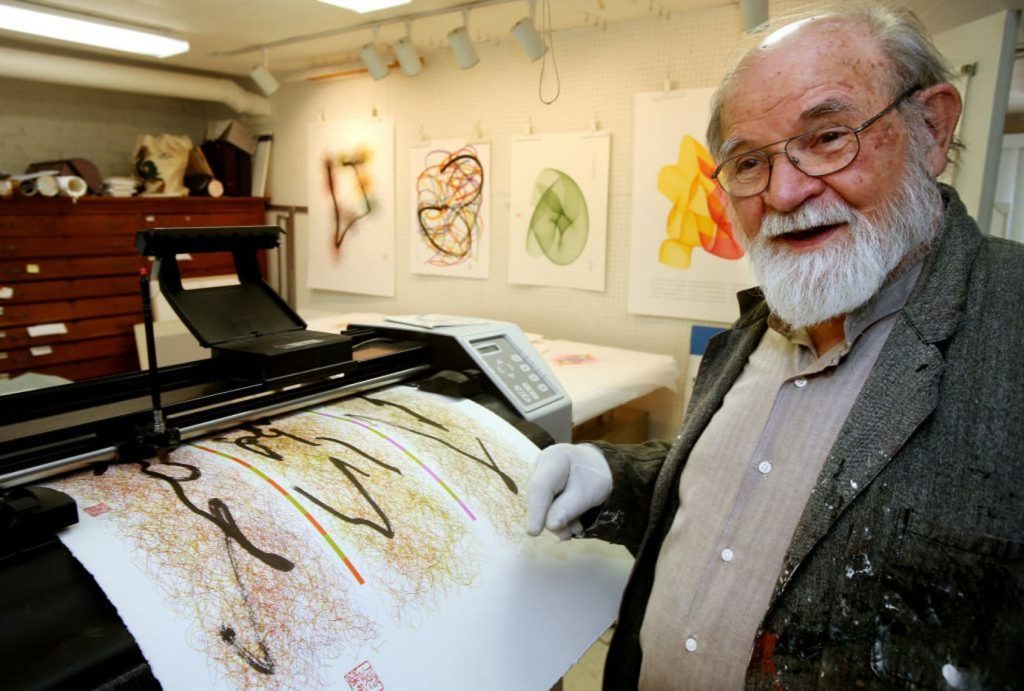

Roman Verostko, an early algorithmic artist, active in computer art since the early 1970s:

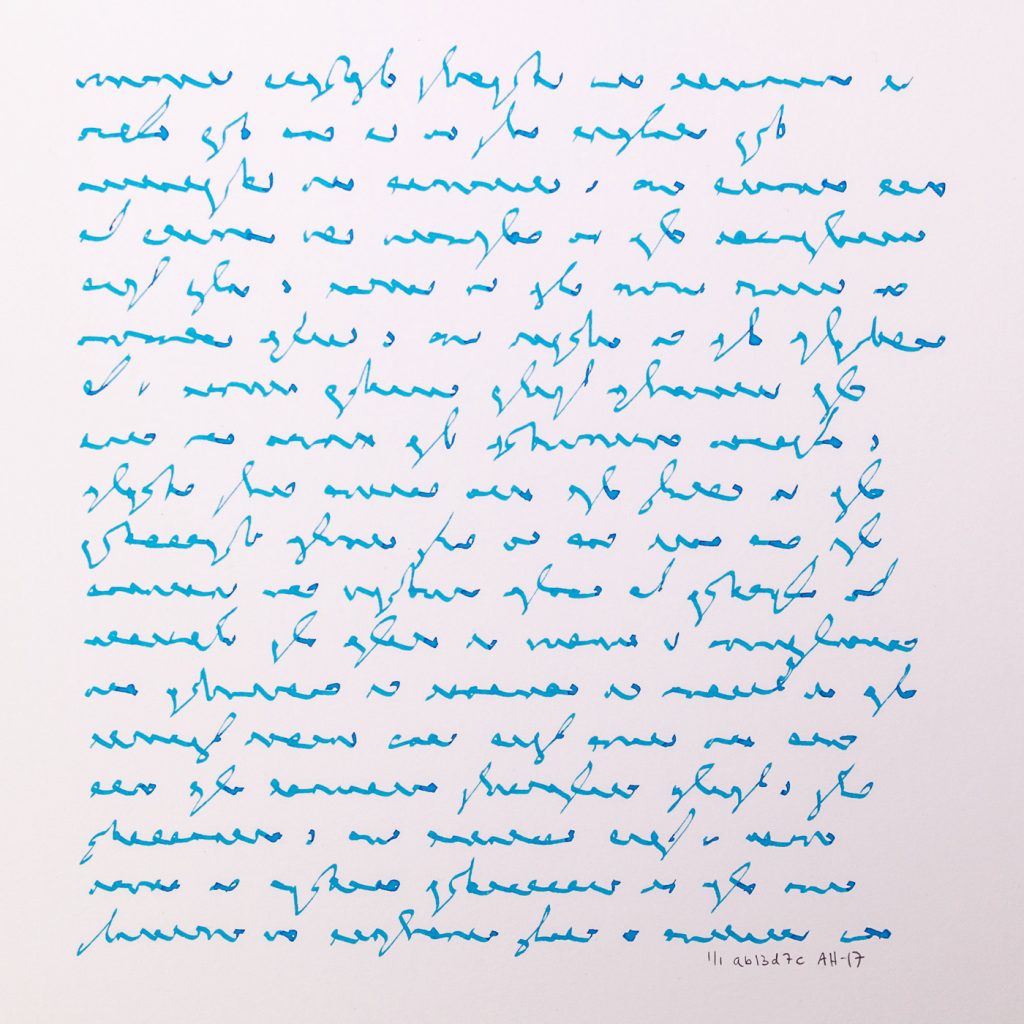

Anders Hoff, Spline Script, 2017 (with writeup)

Other asemic writing projects by Anders Hoff:

Some recent works on Twitter

Currently reading this excellent ancient Egyptian treatise on the pyramids by @bit101 ;-Phttps://t.co/4ugCcfRVdp#generative pic.twitter.com/RVPX32hyXF

— rich (@farty) August 13, 2021

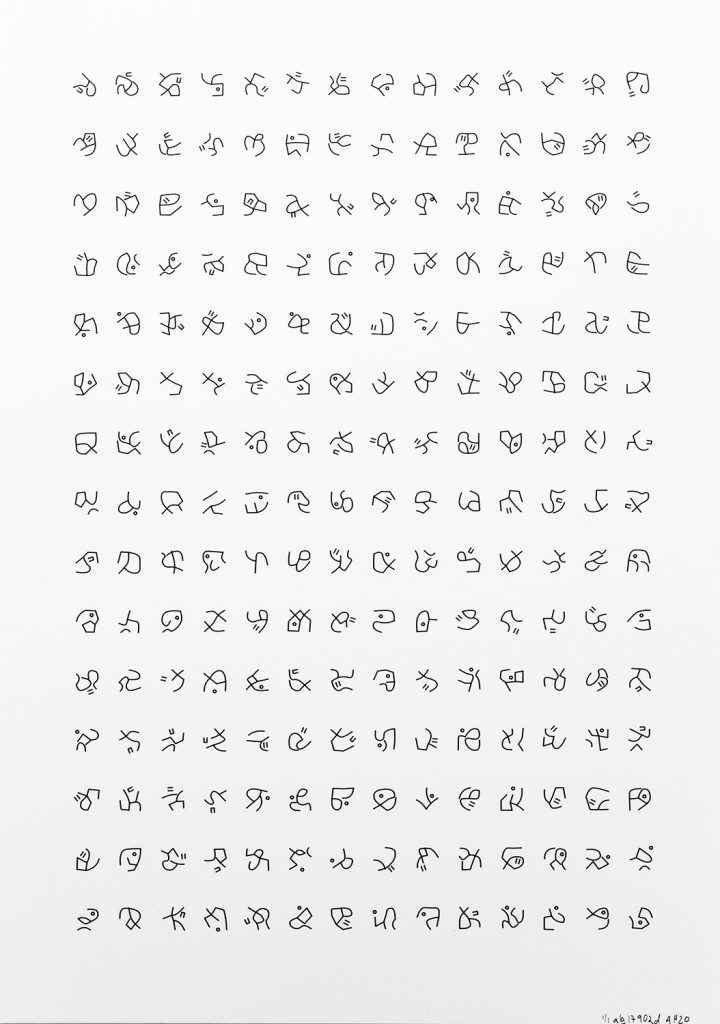

I've been working on #asemic glyphs, each row is a candidate alphabet pic.twitter.com/Eo68GqcGb0

— pentronik (@pentronik) October 31, 2021

pretty cool: Apple's text recognition in photos (new in ios 15, I think?) is fooled: I can select (some of) it. pic.twitter.com/Hl9IJTCyHW

— pentronik (@pentronik) October 31, 2021

second stanza pic.twitter.com/zCVaeDMx3S

— Sarah Ridgley (@sarah_ridgley) June 24, 2021

Letters to No One#generativeart #proceduralart #creativecoding pic.twitter.com/qGt5z5Mz7w

— arthu.R | (@arthurstats_) October 28, 2021

Other Links

- Four Experiments in Handwriting with a Neural Network

- Caroline Hermans, Asemic

- Allison Parrish syllabus

Readings

- Aima, Rahel. “Definition Not Found.” Real Life, Sept. 2016.

- Callich, Ty Casey. “Mean Less: My Experience With Asemic Writing.” 12 Oct. 2016.

- Bury, Louis. “Mirtha Dermisache’s Writing Is a Rorschach Test.” Hyperallergic, 24 June 2018.

- Ingold, Tim. Lines : A Brief History. Chapter 5 Drawing, writing and calligraphy (pp. 137-168).

- Boice, Robert, and Patricia E. Meyers. “Two Parallel Traditions: Automatic Writing and Free Writing.” Written Communication, vol. 3, no. 4, Oct. 1986, pp. 471–90. SAGE Journals, doi:10.1177/0741088386003004004.

A Possible Assignment

Write a computer program that generates forms that resemble writing.

Think carefully about what constitutes writing. From Wikipedia:

Writing is a medium of human communication that represents language and emotion with signs and symbols. In most languages, writing is a complement to speech or spoken language. Writing is not a language, but a tool used to make languages readable. Within a language system, writing relies on many of the same structures as speech, such as vocabulary, grammar, and semantics, with the added dependency of a system of signs or symbols. The result of writing is called text, and the recipient of text is called a reader. Motivations for writing include publication, storytelling, correspondence, record keeping and diary. Writing has been instrumental in keeping history, maintaining culture, dissemination of knowledge through the media and the formation of legal systems.

Please read the Wikipedia article on Writing Systems, which I quote here:

The general attributes of writing systems can be placed into broad categories such as alphabets, syllabaries, or logographies. Any particular system can have attributes of more than one category. In the alphabetic category, there is a standard set of letters (basic written symbols or graphemes) of consonants and vowels that encode based on the general principle that the letters (or letter pair/groups) represent speech sounds. In a syllabary, each symbol correlates to a syllable or mora. In a logography, each character represents a word, morpheme, or other semantic units. Other categories include abjads, which differ from alphabets in that vowels are not indicated, and abugidas or alphasyllabaries, with each character representing a consonant–vowel pairing. Alphabets typically use a set of 20-to-35 symbols to fully express a language, whereas syllabaries can have 80-to-100, and logographies may have several hundreds of symbols. Most systems will typically have an ordering of its symbol elements so that groups of them can be coded into larger clusters like words or acronyms (generally lexemes), giving rise to many more possibilities (permutations) in meanings than the symbols can convey by themselves. Systems will also enable the stringing together of these smaller groupings (sometimes referred to by the generic term ‘character strings’) in order to enable a full expression of the language.

Give thought to your symbols: how they are (individually) composed, and how they are visually sequenced into higher-level ordered structures.