Processes that centred on measurement did not always have to dispense with the pictorial…

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/You_Press_the_Button,_We_Do_the_Rest

Sarah Lewis explores the relationship between racism and the camera. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/25/lens/sarah-lewis-racial-bias-photography.html

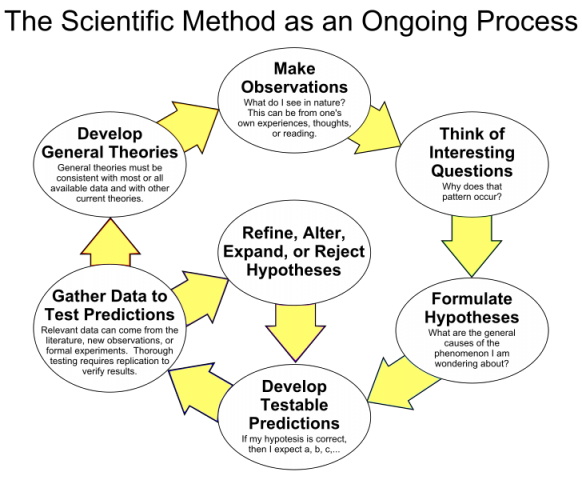

What I found to be most enlightening about the reading is the strenuous correlation between anthropometry and scientific racism and the impact these ideas had on the history of photography. This reading helped me reconsider antiquated and “newer” technologies ability to measure and classify the world around us. The author allows us to re-examine photography’s complicated relationship with truth and objectivity. It’s been eye-opening to recontextualize my relationship with the image through an evidence based practice. I’m excited to continue to explore a methodology that is adaptive and considers the boundaries of the device/mechanism.

Artworks that came to mind while reading:

Lisa Reihana is a multi-disciplinary artist whose practice spans film, sculpture, costume and body adornment, text and photography.

—————————————————————————————

The photographs listed below help me reflect on the limitations of our tools as well as our complex history and relationship with the outside world.

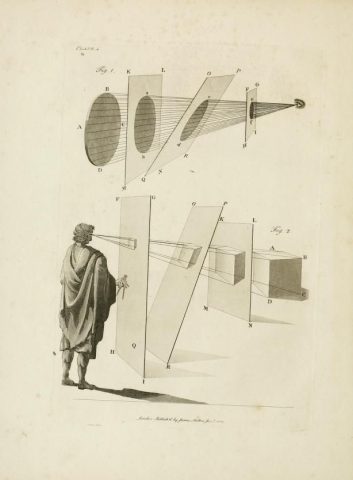

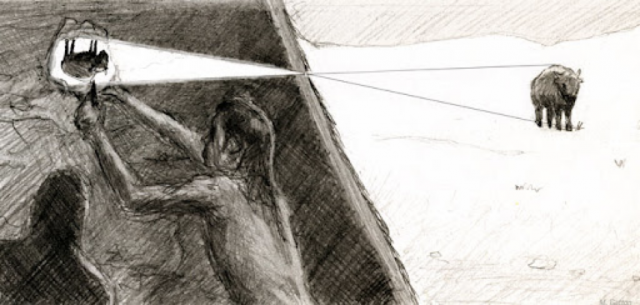

Fig. 10: Visual Perspective: The Young Painter’s Maulstick – James Malton (1800)

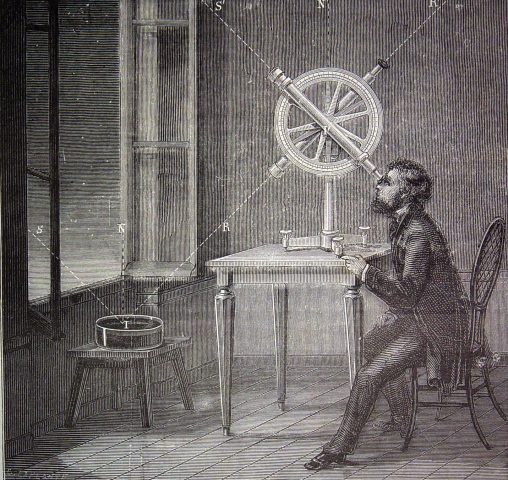

Estudio experimental de las leyes de la reflexión de la luz.

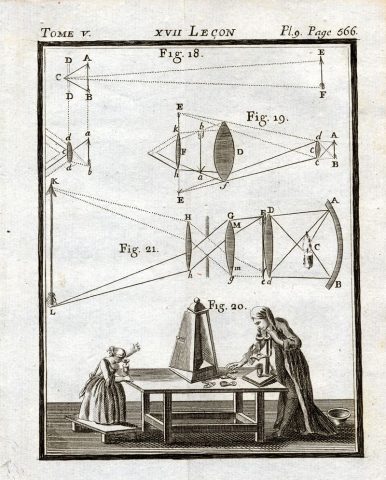

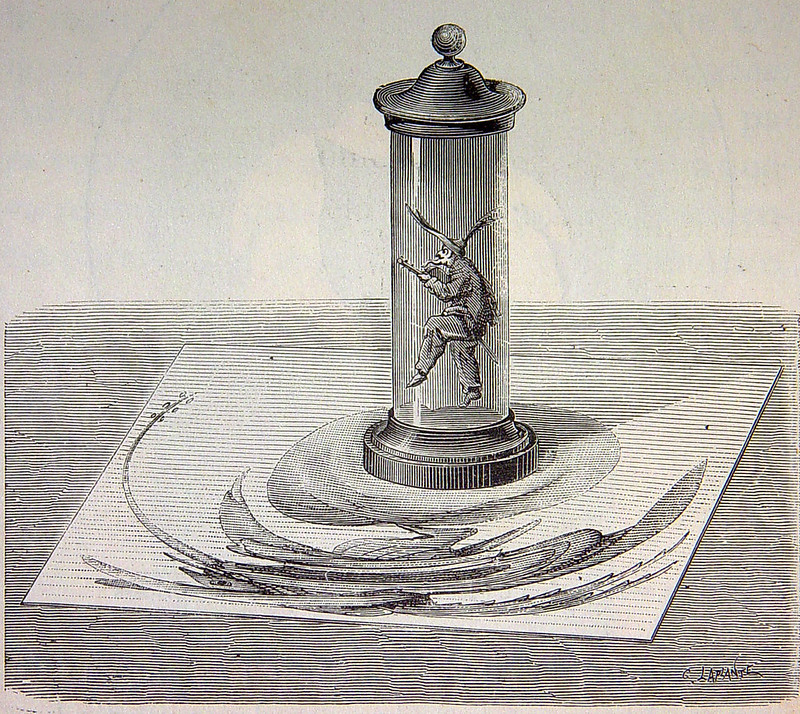

Jean Antoine Nollet: Leçons de Physique expérimentale, 1764, vol. 5

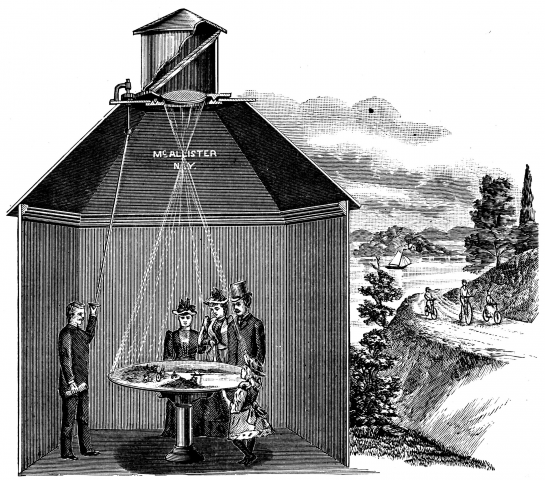

Camera Obscura, Catalogue, William Y. McAllister, New York, c. 1890

http://paleo-camera.com

http://paleo-camera.com