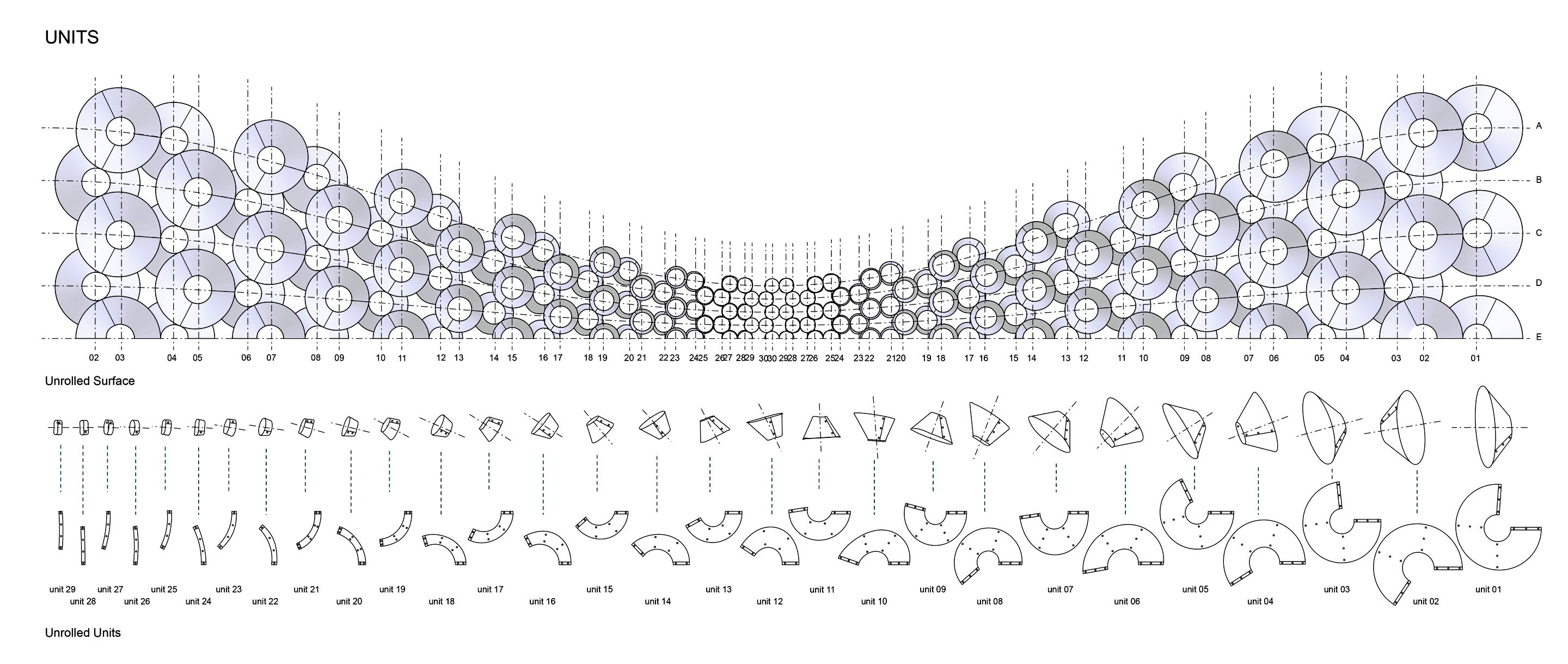

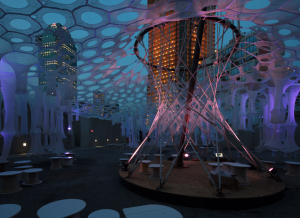

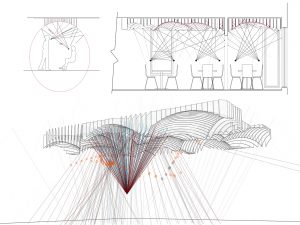

Andrew Kudless takes basic geometry alongside nature in order to create designs that seem to use less materials, but also create strong structures. A lot of his work can be used as a replacement/upgrade for current objects we have now as well as buildings. I am inspired as a designer because being able to create unique patterns while also considering the logistics of it and using the nature’s strongest forms, is something that is difficult to achieve. His simple yet mathematical designs creates another pathway for other designers to consider what nature and years or math research has to offer. The algorithm that generates this work derives from patterns found in nature and relates it to geometrical patterns and tries to find a way where the two creates the best results for a certain object. Andrew Kudless expresses art in his work by choosing which patterns go together and whether or not he decides to create a complicated structure or creates a structure that provides the minimum in order to convey his idea.

https://www.pinterest.com/matsys/computational-design/

![[OLD FALL 2018] 15-104 • Introduction to Computing for Creative Practice](../../../../wp-content/uploads/2020/08/stop-banner.png)