Summary

“15 Bricks” is a partial typology of Lego airplanes that are built with the same 15 Legos. These were obtained by asking different CMU students to build an airplane using all of the pieces in a set I chose. I gave 20 people the same 15 Lego pieces and asked each of them to use all the pieces to build an airplane. With so little to work with, they had to reduce the shape of a plane to its most important features, and each person had a unique approach.

Development Process

Initial Ideation/Planning

Of all the typology examples in lecture, I was particularly inspired by the ones that involved many people each contributing something creative, like Kim Dingle’s “The United Shapes of America.” I think these can serve as indirect portraits of the individual participants while also revealing patterns in our collective thoughts about something. I brainstormed things I could ask people to do and/or materials I could ask them to work with, and I landed on Lego as a fun, accessible medium that’s well suited for 3D shapes.

My initial vision as described in my proposal was that I would have a large (hopefully effectively limitless) pool of Legos that participants could use. I then would ask each one to build a spaceship, and I’d record a video of their construction process. I expected highly varied ships, and to really let people’s creativity run wild. Under this scenario, Lego would be simply the medium people were using to construct their spaceships, and it would be the theoretical spaceship designs that were ultimately being recorded and compared in the typology. That didn’t make as much use of the unique properties of Lego as I’d have liked, so I moved away from it and towards the version I ended up using: one where the limited Legos pose a very tight constraint on their construction.

Playtesting and Fine-Tuning Procedure

Now I had to make a few decisions, including what I was going to ask people to make and what bricks I was going to give them to do it. I decided on the first answer in a discussion with Golan. We went with “airplane” because it’s a fairly simple, familiar, and well-defined shape. Unlike, spaceships or cars, there isn’t too much variance in commercial plane design, so I can be pretty sure that most participants have the same thing in mind when they begin (though it’s okay if not all do). This would make it easier to meaningfully compare people’s constructions.

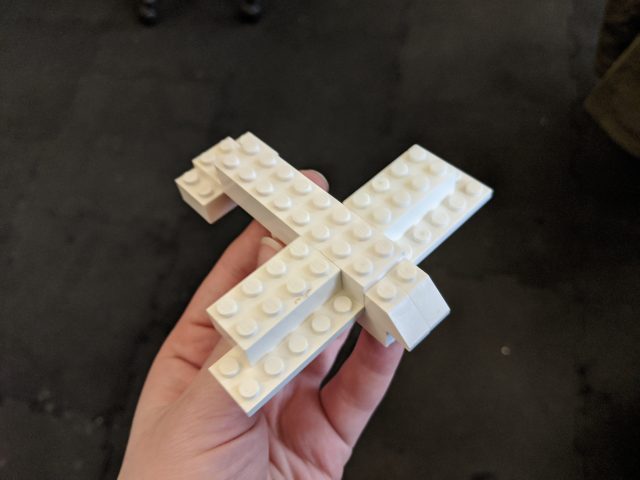

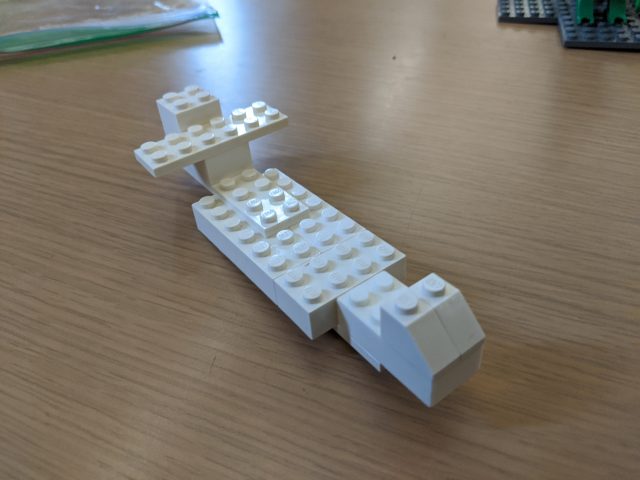

As for what Legos to use, I started by creating a sample set from a box of Legos Golan loaned me. I had a few heuristics in mind: if I believe that a certain piece would only be used one way by everyone (ie. a wheel or windshield) then it was off limits. I wanted to stick to pretty classic, blocky Legos. I also used only white pieces so color was a factor; I wanted people to focus on shape. I also wanted the set to have enough pieces that I got highly varied solutions (can you imagine how boring the 2-piece solutions would be?) but few enough that people had to sacrifice some details.

At about this time, I decided that I wanted to require that all Legos be used in the final construction. I thought that as long as this didn’t significantly hamper people’s creative freedom, it would be a lot more satisfying. The results become “ways to rearrange these same Legos into airplanes” instead of just “many Lego airplanes.”

I tried out my brick set on many people before finding the one I ended up using. One very long flat piece from the original set was used by everyone as part of the wings, so it was no longer interesting, so I removed it. I also reduced the number of bricks slightly, as most people were finishing with bricks to spare and struggling to find uses for the leftover ones (I liked a little bit of this, as it gave me interesting features like wing flaps, exhaust trails, and wheels made out of bricks. But it got to be too much with some of my sets). I was also very pleased with my preliminary results, since the airplanes I was getting looked quite different from each other.

Interestingly, after I decided on my 15-brick set, I found this video of a similar 15-brick Lego building experiment (in this one, participants are given 15 random bricks and told to make anything they want, something I definitely did not want to do). So I guess I’m not the only one who found that to be a pretty good number!

Data Collection

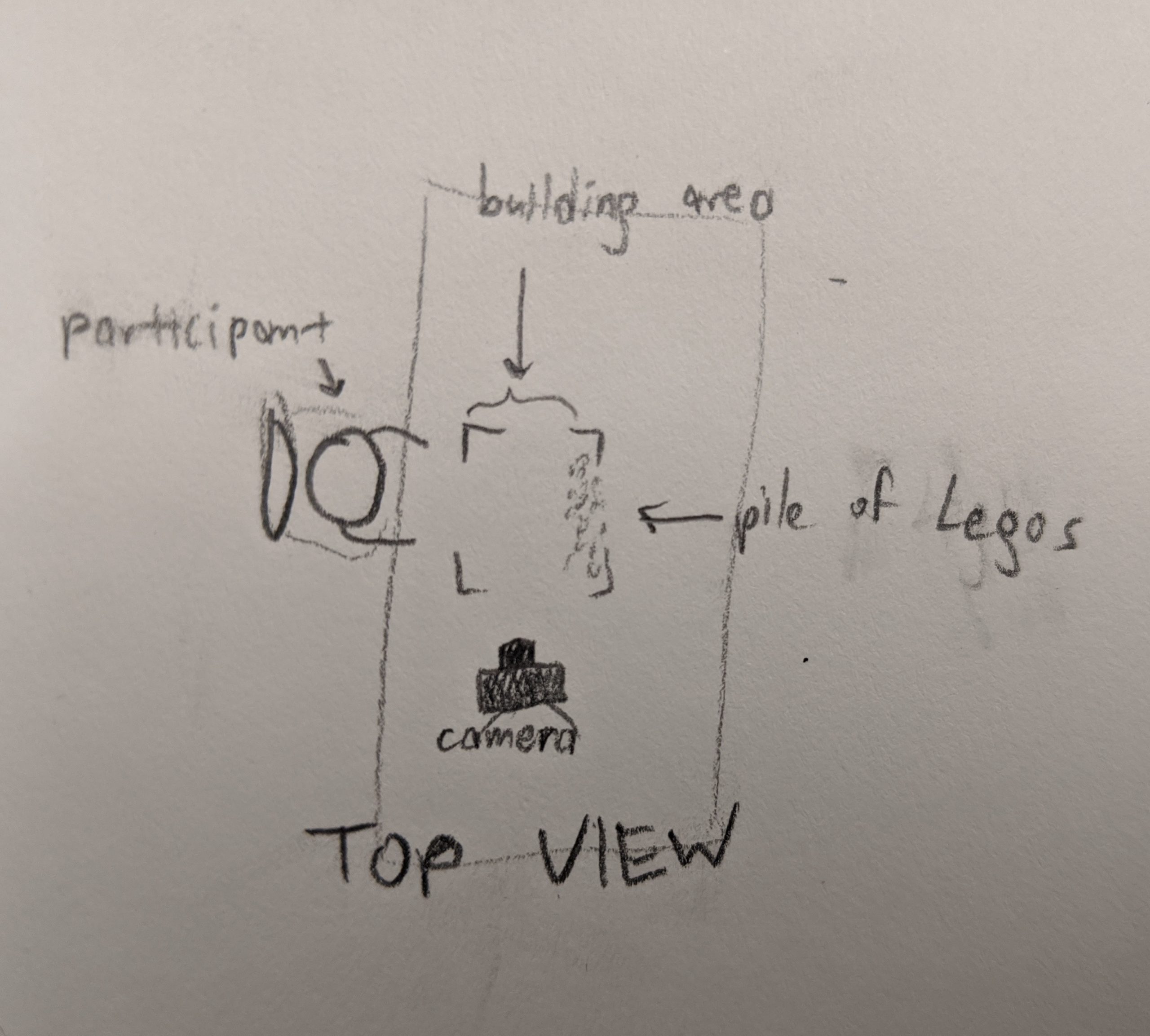

When I first started collecting my airplane designs formally, I wasn’t sure how I would present them. So, just to be safe, I thought I should capture the entire building process, in case I wanted to display the videos of every plane being created or make a list of all the steps people took.

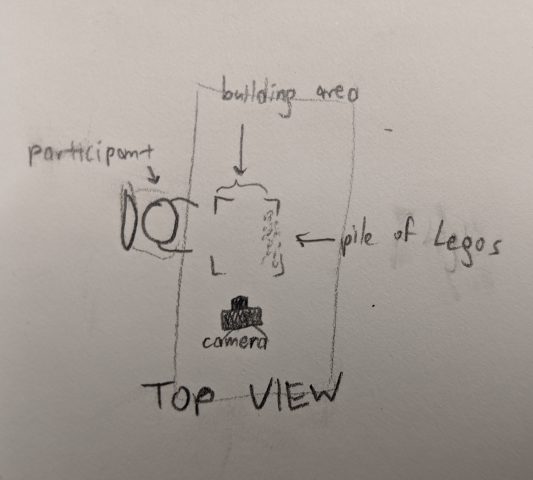

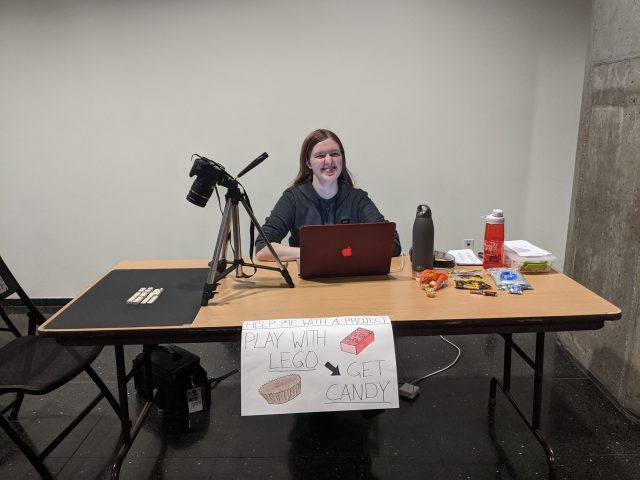

I set up a table in the University Center with the very enticing poster “Play with Lego, Get Candy.” I had a camera set up pointing at the Lego-building area, and I would record any time someone was building anything. I also had people sign a release saying I could use their design in this project and optionally use the footage of their hands in my documentation (which I ended up not doing). I got about fifteen volunteers this way. Some of them found very creative approaches to the problem that weren’t considered “valid” Lego constructions. Initially, I allowed people to do this, but I later decided that I shouldn’t, so a few contributions had to be thrown out.

Once I knew that all I was going to need from people was their plane design (not the footage of their hands), collection was even easier. I’d carry around my little bag of Legos, and when I had a moment, would ask the people around me to make airplanes with them. Then I’d photograph every angle of the planes that were made. After this, I had a total of 20 valid airplanes.

Encoding the Airplanes

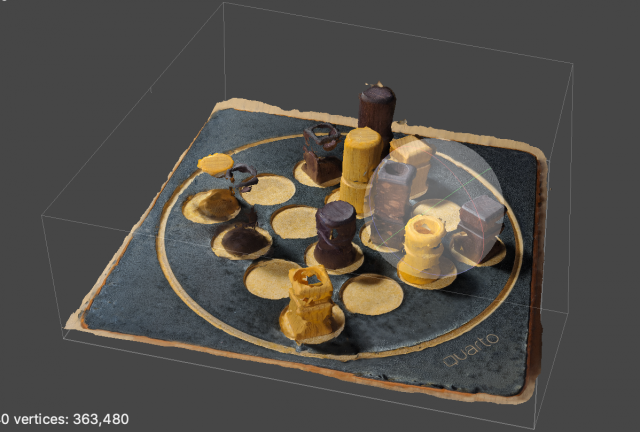

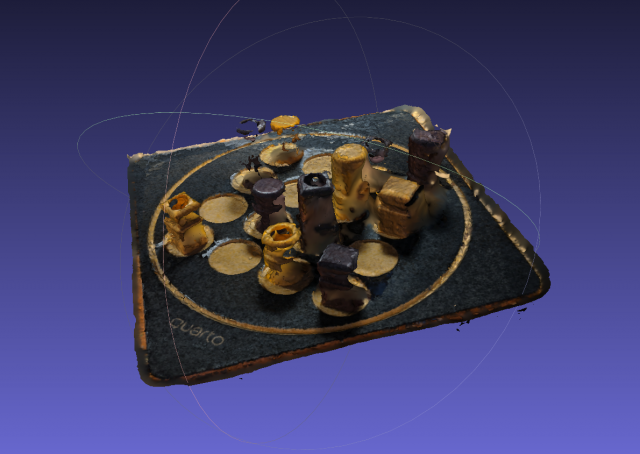

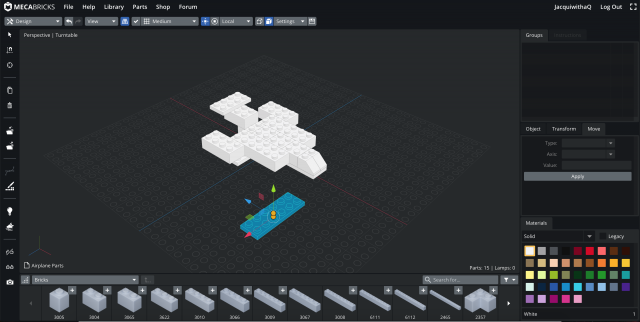

In my initial research for this project, I came across Mecabricks, an in-browser tool for designing Lego models. It has thousands of Lego bricks that you can use, a great interface for moving them and snapping them together, and it’s totally free. Best of all, it has an extension for Blender that lets you animate and render nearly photo-realistic images of your Lego models (if I had bought the paid version, I could have chosen just how scuffed up I wanted the surface of the bricks to look, and how many fingerprints they had on them–how cool!). If you want to make a Lego animation for some reason, I can’t recommend this enough. My only complaint is that the documentation for some features is pretty poor.

I decided to model and render people’s airplanes in Blender because I wanted their contribution to be not the physical figure they created, but their design. Mecabricks models let one uniquely describe a Lego creation with no extraneous detail–exactly what I wanted. It also allowed me to render them all with exactly the same lighting/camera conditions, which is always good for a typology. Finally, it’s a format that people can potentially explore in 3D (Mecabricks has a model-sharing website for this), without the loss I would incur doing something like photogrammetry. The only downside of this decision is that it meant I had to learn Blender, which while probably valuable was not very much fun.

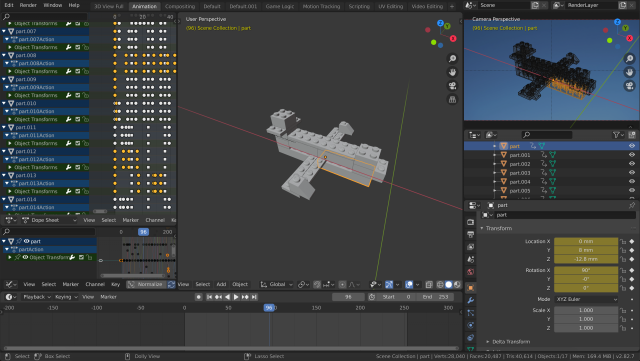

After I put all the models in Blender, I had the idea of animating transitions between them to really drive home the combinatorial element of this: it’s all the same blocks being rearranged every time. I ordered the airplanes based on my own subjective preferences, putting two next to each other when they had something interesting in common that I wanted to highlight. Then I animated all of the bricks moving, which took WAY longer than I thought, but also was pretty rewarding! I find the resulting video (top of this post) extremely satisfying to watch.

Results and Discussion

Below is an image of all 20 rendered airplane designs, ordered by participant first name.

I have really enjoyed comparing and contrasting them so far. Here are some things I’ve noticed:

- Most people used the small sloping bricks as the nose of the plane, but a few did put them on the wings or tail.

- Many people used the two 2×6 flat bricks as the wings, but they were also popular as support bricks for the body of the plane. The 2×8 flat brick was a common substitute, but some people made their wings out of thicker pieces.

- People had pretty different approaches to the tail end of their airplanes, with many adding some small crossbar, some making a very pronounced tail, and some just letting their airplanes taper off.

- People LOVE to make their airplanes symmetric. 19 of the planes are symmetric up to overall shape, and 18 of these are symmetric even down to the exact Lego (somewhat impressive given the fact that I included some odd-sized Legos with no matching partner).

- A few categories of airplane have emerged, like those that are just plus signs, or those that are triangular.

The similarities/patterns above are especially evident in the animated video, I think. You can, for example, watch the slope pieces sit there near the front for many planes in a row.

I’m really happy with this project, but I do wish there were a little more to it. I would love to try this again with a different prompt. Maybe I can get 20 people each to make a Lego chair? Or maybe I can keep scaling down the number of Legos and see at what point they converge with many people making the same thing? Hopefully I can pursue this in the future–I’ve had a lot of fun with this project so far!